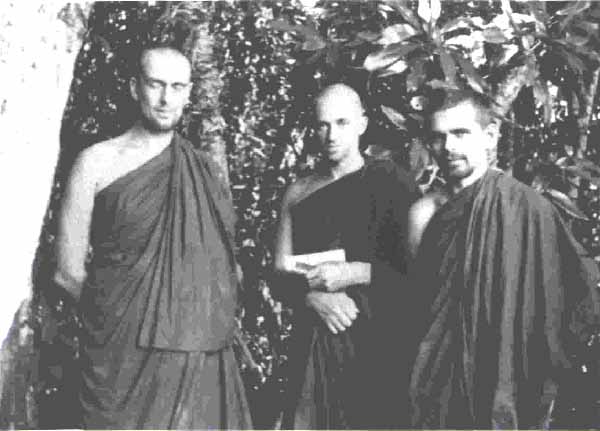

Ven. Ñánavíra, Ven. Ñánamoli and Ven. Ñánavimala

at the Island Hermitage.

Images and the biography below courtesy of Ñánavíra Thera Website

Ñánavíra Thera

Ven. Ñánavíra Thera was born Harold Edward Musson, on the 5th of January, 1920, in a military barracks in England. His father, Edward Lionel Musson, was Captain in the 1st Manchester Regiment stationed in the Salamanca Barracks in Aldershot. A career officer, Edward Musson reached the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, D.S.O., M.C. The father apparently expected his son, an only child, to follow in his footsteps. Some people from his town remembered the youth as a rather solitary teen-ager, living in a duty-bound atmosphere which generated some occasional tendencies toward rebelliousness. He was noticably inclined to introspection and contemplation. A neighbour of the family recalled his telling her, much to her puzzlement, that he often enjoyed walking alone in the London fogs. She also recalled his marked distaste for a tiger-skin proudly displayed by his father in the foyer of "Wivelrod House", the country residence in the Hampshires. It was a trophy of a hunt in India or Burma. His mother, née Laura Emily Mateer, appeared to have been devoted to her son; "possibly over-devoted to him", one person commented, "as her only child". She was deeply sorrowed by her son's departure for Ceylon at the age of 28, and desperately attempted by a visit there to persuade him to forsake his monastic existence and return to England.

The setting of his youth was a greystone mansion, within sight of a fine abbey, in the environs of Alton, a typical and restful English small town in the Hampshiredowns, about an hour southwest of London by road or rail. No doubt the young Musson's life was influenced at least equally by the nearby town of Aldershot, the site of the celebrated military academy. It seems likely, too, that he spent some time during his childhood in India or Southeast Asia. According to an interview -- perhaps not wholly reliable -- published by the journalist and novelist, Mr. Robin Maugham, in a somewhat sensational newspaper in 1965, the young Musson had been significantly affected by a statue of the Buddha which he had seen when his father was commanding a battalion in Burma.

His schooling was at Wellington college -- traditional for scions of military families. He went up to Magdalene College, Cambridge, in 1938, and spent one summer (probably the same year) studying Italian in Perugia, Italy. In June, 1939, he sat for Mathematics, and in 1940, for Modern Languages (in which he earned a "Class One"). In 1939, immediately after the outbreak of war, he enlisted in the Territorial Royal Artillery. In July, 1941, he was commissioned 2nd Lieutenant in the Intelligence Corps, for which his knowledge of modern languages was doubtless an asset (he was an interrogator). In October, 1942, he was promoted to Lieutenant, and in April, 1944, to Temporary Captain. His overseas service with the British Eighth Army was primarily in Italy, from 1943 to 1946. A family acquaintance spoke of him, however, as having "completely resented warfare". In a letter, written in 1964 in Ceylon, may be found the sardonic comments that he had much enjoyed travel before the wartime army, and that he agreed with the classification of intelligence into three classes, "human, animal, and military". He received a B.A. degree in Modern and Medieval Languages from Cambridge University for six terms of university study together with three terms allowed for military service.

Little can be surmised concerning his initial interest in Buddhism. In his university days, James Joyce's novel, Ulysses, had exerted a powerful influence on him because (according to a letter dated 28.ii.1965) Joyce had held up a mirror to the "average sensual Western man" and had shown that "nothing matters". He wrote of himself (19.v.1964) as having always preferred ideas to images. Poetry, he once noted, only "pleased" him. Alongside this penchant, as one might put it, for the realistic view over fantasy, was a great love of music, especially Mozart, the late Beethoven, Bartok and Stravinsky. The first public indication of an involvement with Buddhist thought was his translation of an Italian study, written in 1943 by J. Evola, and published in English by Luzac (London) in 1951 under the title, The Doctrine of Awakening -- A Study on the Buddhist Ascesis. In a letter written in 1964, Ñánavíra Thera expressed "considerable reserves" about the soundness of the book. Apparently he had chanced upon the Italian work during his wartime assignment in Italy.

After the war, Musson found himself, according to his own account, in no special need of money (19.xi.1964) and highly dissatisfied with his life. In 1948, he ran into a sometime fellow-officer and friend, Osbert Moore, who felt similarly dissatisfied. Osbert Moore was born on the 25th of June, 1905, in England and graduated at Exeter College, Oxford. His interest in Buddhism was roused by reading Evola's book, later translated into English by his friend Musson, during his time as an army staff-officer in Italy. After the war he held the post of Assistant head of the BBC Italian section at Bush House. In 1948, they both decided to settle their few affairs in England, put the Western milieu behind them, and go to Ceylon to become Buddhist monks. In 1949 both received Novice Ordination at the Island Hermitage, Dodanduwa (from Ven. Ñánatiloka), and in 1950 the Higher Ordination as bhikkhus at the Vajiráráma monastery, Colombo. Osbert Moore was given the monastic name of Ñánamoli, and Harold Musson that of Ñánavíra. Both returned soon to the Island Hermitage (an island monastery situated in a lagoon of south Ceylon), where the Ven. Ñánamoli spent almost his entire monk life of 11 years, until his sudden death on the 8th of March, 1960, due to heart failure (coronary thrombosis). He is remembered for his outstanding scholarly work in translating from the Pāḷi into lucid English some of the most difficult texts of Theraváda Buddhism.

Ven. Ñánavíra was more solitary and moved from the Island Hermitage to a remote section of southeast Ceylon, where he lived alone for the rest of his life in a one-room, brick-and-plaster kuti (hut) with a tile roof, about a mile from the village of Bundala, on the edge of a large game-preserve. It was an all-day, uncomfortable bus-ride from Colombo, where he had to repair at times for medical treatment. The change of life was not physically easy. Not long after arriving in Ceylon, he contracted a severe case of amoebiasis which continued to plague him for the next fifteen years. The tropical climate and the local food must have been taxing for the physically ailing Westerner. Bhikkhus accept food which is offered to them by laypeople, and this custom often leaves them with few options concerning their diet. Some indication of the harsh physical effects of the amoebiasis may be glimpsed in the observation of Ven. Ñánasumana, an American bhikkhu who had met Ven. Ñánavíra in October, 1963, and began regular study with him. In a letter dated 30.x.1964, Ñánasumana wrote of "a man of about 60 years.... He speaks and I learn". In 1964, Ven. Ñánavíra was only 44 years old. He died a year later, on the 5th of July, 1965, by his own hand and deliberate decision. Suicide is of course regarded with peculiar horror and condemnation in our Judaeo-Christian civilisation, as an offence against God, perhaps incurring eternal torture in Hell, and even as a legal offence against the proprietary State. Ñánavíra Thera wrote extensively and carefully on the question of suicide, which arose for him because of the severity of the amoebiasis and other health problems. He mentioned the occurrence of a nervous disorder associated with the chronic amoebiasis and the prescribed medication, which combined to "leave me with little hope of making any further progress in the Buddhasásana in this life". But it is doubtless best to allow the late Thera to speak for himself in his letters. Only after a careful reading of them should the reader form his own opinion.

Ven. Ñánavíra's writings fall into two periods: from 1950 till 1960 (the Early Writings), and from 1960 till 1965 (included in Clearing the Path). On 22.iii.1963, the author wrote in a letter:

...With regard to any of my past writings that you may come across..., I would ask you to treat with great reserve anything dated before 1960, about which time certain of my views underwent a modification. If this is forgotten you may be puzzled by inconsistencies between earlier and later writings....

Before use is made of the Early Writings, the reader should be familiar with Clearing the Path, which sets the former collection (serving as a supplement to the latter) in the proper perspective.

The earliest known piece of writing by Ven. Ñánavíra Thera on the Dhamma is found in his "Translator's Foreword" to The Doctrine of Awakening -- A Study on the Buddhist Ascesis (translated from the Italian -- La Dottrina Del Risveglio by J. Evola -- by H. E. Musson and published by Luzac & Company, London, 1951):

Of the many books published in Italy and Germany by J. Evola, this is the first to be translated into English. The book needs no apology; the subject -- Buddhism -- is sufficient guarantee of that. But the author has, it seems to me, recaptured the spirit of Buddhism in its original form, and his schematic and uncompromising approach will have rendered an inestimable service even if it does no more than clear away some of the wooly ideas that have gathered round the central figure, Prince Siddhattha, and round the doctrine that he disclosed.

The real significance of the book, however, lies not in its value as a weapon in a dusty battle between scholars, but in its encouragement of a practical application of the doctrine it discusses. The author has not only examined the principles on which Buddhism was originally based, but he has also described in some detail the actual process of "ascesis" or self-training that was practised by the early Buddhists. This Study, moreover, does not stop here; it maintains throughout that the doctrine of the Buddha is capable of application even to-day by any Western man who really has the vocation. But the undertaking was never easy, and the number who, in this modern world, will succeed in pursuing it to its conclusion is not likely to be large.

H. E. M.

London

April, 1948.

Having come to Ceylon and after acquainting themselves thoroughly with the Pāḷi Suttas, the two English monks also explored many modes of Western thought -- even quantum mechanics! -- through reading and discussion. When Ven. Ñánavíra left Ven. Ñánamoli at the Island Hermitage to live on his own, the two friends continued their discussions through voluminous correspondence which lasted until 1960, the year of the Ven. Ñánamoli's death. Increasingly they found that the Western thinkers most relevant to their interests were those belonging to the closely allied schools of phenomenology and existentialism, to whom they found themselves indebted for clearing away a lot of mistaken notions with which they had burdened themselves. These letters make clear the nature of that debt; they also make clear the limitations which the Ven. Ñánavíra saw in those thinkers. He is insistent that although for certain individuals their value may be great, yet eventually one must go beyond them if one is to arrive at the essence of the Buddha's Teaching. Existentialism, then, is in his view an approach to the Buddha's Teaching and not a substitute for it.

The major portion of the Early Writings consists of written to the late Ven. Ñánamoli Thera. With the manuscript letters, which were preserved by the recipient (tied up in bundles, one of which, containing letters written between August and December 1958, was not found), were found draft copies of some of the replies which were sent to Ven. Ñánavíra Thera. These have been included here; it should be remembered, however, that they are only draft copies and not final versions. Following these are a few written to Ven. Ñánavíra Thera's chief supporters, Mr. and Mrs. P. The two essays following the letters were published (the Sketch was reprinted several times) in abbreviated form: the texts reproduced here are taken from the author's typescripts, which may be regarded as the definitive versions. Following these two essays are the contents of the author's Commonplace Book, and then Marginalia, being the comments the author made in the margins of various books which engaged him (together with the text commented upon, where useful). Finally there is a collection of various papers discovered after their author's death: notes, translations, etc. Apart from the two essays, the other texts have been edited, but hopefully all the important passages are included here.

The difference between Ven. Ñánavíra's early writings and those included in Clearing the Path is very marked and striking. The early texts show a man who, in his own thinking and discussion with others, earnestly seeks a way of approach to the heart of the Buddha's Teaching, by repeated trial-and-error. This seeking has eventually yielded its fruit when, though suffering from amoebiasis (which prevented him to a great degree from practising samádhi, or mental concentration), Ven. Ñánavíra apparently attained sotápatti, or Stream-entry, on 26.vi.1959, which he has himself described in a letter "to be opened in the event of my death". A person who has "entered the stream" has ipso facto abandoned personality-view (sakkáya-ditthi), which is the self-view implicit in the experience of an ordinary ignorant worldling, and understood the essential meaning of the Buddha's teaching on the Four Noble Truths. Ven. Ñánavíra's writings after 1960 express just this kind of certainty: no more groping in the dark, no more doubt or speculative guessing.

No later than February 1963, the Ven. Ñánavíra Thera completed a book called Notes on Dhamma (1960-1963), which was privately published by the Honourable Lionel Samaratunga in the same year. Following production of that volume, the author amended and added to the text, leaving at his death an expanded typescript, indicated by the titular expansion of its dates, (1960-1965). Notes on Dhamma has been variously described as "arrogant, scathing, and condescending", as "a fantastic system", and as "the most important book to be written in this century". The Ven. Ñánavíra Thera himself remarked of the book that "it is vain to hope that it is going to win general approval... but I do allow myself to hope that a few individuals... will have private transformations of their way of thinking as a result of reading them".

And indeed, the influence of Notes on Dhamma on Buddhist thinkers continues to increase more than three decades after its publication. Inasmuch as the first edition, long out of print, consisted of only 250 copies, how is it that this book has aroused such extraordinary interest and controversy? The answer, it seems, is to be discovered not only in the specific content of the Notes but in their general attitude, their view and direction. In describing that attitude their author wrote of the Notes that they "attempt to provide an intellectual basis for the understanding of the Suttas without abandoning saddhá"; that they "have been written with the purpose of clearing away a mass of dead matter which is choking the Suttas"; and that, above all, "the Notes are designed to be an invitation to the reader to come and share the author's point of view".

That point of view -- achieved by the Ven. Ñánavíra through dedicated self-investigation using the Buddha's Teaching as a guide -- is described unflinchingly in the Notes, which assume that "the reader's sole interest in the Pāḷi Suttas is a concern for his own welfare". However, the Notes, with their admitted intellectual and conceptual difficulties, are not the only way to discuss right view or to offer right-view guidance. The letters which are collected here are not only "something of a commentary on the Notes"; they are, independently, a lucid discussion of how an individual concerned fundamentally with self-disclosure deals with the dilemma of finding himself in an intolerable situation, where the least undesirable alternative is suicide.

With openness, calmness, and considerable wit the Ven. Ñánavíra discusses with his correspondents (including his doctor, a judge, a provincial businessman, a barrister, a British diplomat, and another British citizen) the illnesses that plague him and what he can and cannot do about them, and about his own existence. His life as a Buddhist monk in a remote jungle abode is not incidental to the philosophy he expounds: the two are different aspects of the same thing, namely a vision that penetrates into the human situation both as universal and as particular, and recognizes that it is this situation which it is the business of each of us to resolve for ourselves. In presenting this view the Ven. Ñánavíra offers a contemporary exposition of the Teaching of the Buddha. In living this view he evokes a dramatic situation wherein an individual resolutely faces those questions which every lucid person must eventually face.

Most of the editorial work connected with Ven. Ñánavíra Thera's writings was performed -- as a labour of love -- by the late Sámanera Bodhesako (Robert Smith), who died in Kathmandu in 1988, aged 49, from a sudden intestinal hernia while on a return journey to the United States to join his father for the latter's eightieth birthday celebration. During the last years of his life in Sri Lanka he founded Path Press which published Clearing the Path: Writings of Ñánavíra Thera (1960-1965). He also worked as editor for the Buddhist Publication Society in Kandy which published The Tragic, The Comic & The Personal: Selected Letters of Ñánavíra Thera (Wheel 339/341) in 1987. Prof. Forrest Williams of the University of Colorado also participated as the co-editor of Clearing the Path.

Clearing the Path has so far been translated into Czech, Dutch, and Serbo-Croatian (only Notes on Dhamma). There are also plans for a second revised edition of the English original, which seems to be out of print now, although a few copies should still be available from Wisdom Books.

§

References

The Doctrine of Awakening -- A Study on the Buddhist Ascesis (translated from the Italian -- La Dottrina Del Risveglio by J. Evola -- by H. E. Musson and published by Luzac & Company, London, 1951):

The Legend of Bundala

by Kingsley Heendeniya

More than 50 years ago, I had the once-in-a-lifetime fortune to meet Harold Musson and Osbert Moore who came to Sri Lanka on an exploratory visit to study Buddhism. They had met in the British Secret Service during the World War when assigned to interrogate prisoners in Italy.

Harold born on in 1920 at Aldershot graduating in 1940 with a First Class in Modern Languages from Cambridge and also studied Mathematics. Osbert, born in 1905 graduated from Oxford and was an Executive Director in the BBC Italian section of Bush House. In Italy, Harold came across a book on Buddhism written by Evola and published an English translation 'The Doctrine of Awakening – A Study on Buddhist Ascesis' [Luzac, London, 1951].

After the war, Harold, an only child and heir to Coal Mines in Wales returned to a bohemian life in London. Osbert went back to the BBC. One evening, they met in a pub and during a long discussion they found no meaning in their pursuits and in the trivialities of post-war life. It destined them to visit the Island Hermitage, be ordained by its German High Priest Nanathiloka – Harold as Ñanavira and Osbert as Ñanamoli – to live, strive, achieve and die in the wilds of Sri Lanka. This is their story.

I graduated as a doctor in 1958 and the following year volunteered to serve as Medical Officer of Health at Hambantota. Ñanavira found the humidity of the Island Hermitage affecting his health and the company of others interfering. About two years before me, he came to Hambantota for its dry climate, and his search for solitude led him to the forest of Bundala, 13 miles further south. Bundala was then a remote hamlet with very poor people living in wattle and daub mud huts, subsisting on burn and slash cultivation and fishing. I am told it was an ancient village of the caste of washerwomen and men serving King Duttugemunu, around 1500 years ago.

Dense forest

From the main highway to Tissamaharama, a thin gravel road ran through the jungle to the village. Just past a culvert at a bend is a clearing of the scrub land and rolling sand where, after the rains, flamingos come every year to feed. And hidden in a crop of dense forest is a footpath leading to the dwelling house or kuti designed and built by Ñanavira. As even now, all around was thick virgin forest with wild elephants, leopards, wild boar, monkeys, endemic and migrating birds feeding in the lagoons; and infested with poisonous snakes, the deadly Russel's viper (polonga) and the cobra. The area is now the Bundala Forest Reserve.

The kuti had one room about 8 feet square entered along a 12 feet corridor built for walking meditation. It had a stone bed and as I remember, a table, chair and some books. Ñanavira built a latrine and an earthen water storage structure. Nearby, if you walk through the jungle is the sea, stretching without land all the way to Antarctica. It is an idyllic place to practice the Dhamma as recommended by the Buddha. Whenever I visited him in the stillness and cool of evenings, the aroma of solitude and the soft rays of the setting sun would seep into me the meaning of tranquillity. But seasonal droughts in July can be enervating and one day I met Ñanavira bathing in the culvert, in a drying pool slaked with mud. Later, he was taken to Colombo to syringe the mud from his ears! Another time, he was treated for bursitis of both knees from unrelenting practice of anapanasati meditation. This is how an Englishman learned and practiced the Dhamma.

My visits were for not more than an hour, mainly to know if he wanted my mother to send him anything. [My mother Clara, was the founder and secretary of the Sasanadhara Kantha Samitiya or women's society she built with other ladies to look after the needs of the monks of the Island Hermitage]. One day, I saw him writing with a pencil stub less than one inch – and yet Ñanavira wanted nothing except some medicine for his chronic bowel disorder, treated as for amoebiasis. Letters published after his death reveal a long correspondence with a doctor about ups and downs and its progress to become incurable. At the same time, he answered profound philosophical questions on Dhamma. As time went by, pain and frequent diarrhoea attacks interfered with concentration. The drugs prescribed produced poisonous effects. In a discourse to King Passanedi, the Buddha has described five conditions for striving, the second of which is ability for good digestion. In a letter to his doctor in December 1962 he said, 'Although I wrote to you in my last letter that I was oscillating between the extremes of disrobing and suicide; a return to lay life would be pure weakness, and in any case I should be miserable”. So, on July 5th 1965, he decided to put an end to his life.

But I am now getting ahead of my memories. Ñanamoli had a fine sense of self-deprecating humour and enjoyed robust health. Among other work, he translated to English the Visuddhimagga of Buddhagosa and never left the island from the day of his ordination. After completing his magnum opus, he decided to go on a pilgrimage with the then High Priest of the Hermitage. The rules of the Vinaya do not permit, among other things, handling of money. My mother's samithiya attended to all that. So, when my father put Ñanamoli in the train at the Fort railway station, he asked “Sir, when are you returning?” Ñanamoli, smiled and said “Bertie, how do you know I am returning?” He died of a heart attack on a desolate gravel road in the backwoods of Kurunegala, about 25 years after walking the lush carpets of the BBC. The body was taken by bullock cart to a hospital and later, after the inquest, for the funeral in Colombo. My mother sent me a telegram to inform Ñanavira.

I went to Bundala in the afternoon around 3 O'clock. I parked the car near the culvert and walked through the jungle looking around for elephants. I met Ñanavira at a small clearing in the footpath. He was dying his robe in the way prescribed by the Buddha. The first thing he said was “Kingsley, why are you coming at this time”? I was then in my late twenties and he a little older. We were like friends and stupidly, I beat around the bush. He interrupted, “Have you come to tell me that Ñanamoli has died?” The casualness with which he said it hangs in my memory. When I explained he continued to dye the robes and wring them as if the news meant nothing. He said Ñanamoli had written to him about the pilgrimage and left instructions to settle his affairs in the event of death. Ñanamoli had a presentiment of death! I told Ñanavira that I am unable to take him by car for the funeral in Colombo because I did not have leave. Can he travel by bus? Without the slightest hesitation, he got ready with his bowl slung over the shoulder and walked with me to the car. In the distance we saw two wild elephants and he remarked: “Kingsley, the problem for human beings is boredom. Animals are never bored. Do not read the Suttas because you will then give up the lay life”. He knew I had just got married. He had never made any attempt to teach me the Dhamma though he had detected a dormant reflexive nature in me. One evening, I was standing on the beach, alone. There was the horizon in the setting sun and the clear blue vault above, the sound of crashing waves and an ethereal emptiness. I felt utterly insignificant in the immensity of the universe and had an overpowering feeling that nothing in life mattered. I had told Ñanavira about this strange glimpse of an insight.

I brought him to Hambantota and lodged him at a small temple near my residence. The next day after a noon day meal my wife served, I took him to the town bus stand. It was about 1 PM. The bus to Colombo starts from Tissamaharama. It was packed when it arrived. Ñanavira got in. I paid for his ticket. He stood in the gangway with his bowl slung over the shoulder holding the handrail – tall, imposing and indifferent. It occurred to me that here was a man who at one time could have bought the bus on the spot! I inquired if there was anyone willing to pay for a taxi in Colombo to Vajiraramaya and I shall give the money. A man who was seated immediately got up, gave it to Ñanavira and assured he will attend to everything. That was the last time I saw Ñanavira. Shortly afterwards, I went on transfer to the North Central Province and we corresponded briefly. He had a peculiar way of folding letters into the envelope, as in origami. Unfortunately, I have not preserved any.

A few years before, Ñanavira's mother flew to Sri Lanka to take her son home. His father had died and she was alone. My mother arranged for her to stay at the Mt. Lavinia Hotel. Ñanavira met her at Vajiraramaya in Colombo. His pagan life as she thought, and the bizarre change devastated her in her only child. She recoiled to see him eating with his fingers from the begging bowl. Ñanavira tried and failed to explain. He returned to his forest refuge. The mother flew back to London – and died in two weeks.

I met Kate Burvill from the Tate Art Gallery [presently with Thames and Hudson] in a strange way in Colombo, in January 1999. She is a niece of Ñanavira and had come on a holiday to Sri Lanka for the first time, combining it with a search for information about her uncle. She visited the Island Hermitage and the monks there referred her to me. She telephoned from the Galle Face Hotel and we met. The next day I took her to Bundala – to give her a feeling for the wilderness, the solitude, the ambience and peace where her uncle lived strived and entered the Path when Kate was only 3 years old.

At the kuti, we met an English monk, a former telecommunication engineer, who gave her the library copy of 'Clearing the Path'. He said there was a waiting list in Europe for the kuti. Later in the evening, though our driver protested about wild elephants on the road in the gathering night, I arranged for her to meet the mother of the village headman of Bundala. The old lady re-told the story of Ñanavira. The headman, she said was a three-month baby in her womb when tragedy struck the village.

This is the way Ñanavira died. One evening, I saw his skin inflamed with insect bites and gave him a vial of ethyl chloride spray used those days as a local anaesthetic. He used it and obtained another from my mother. By now his sickness had worsened. He had attempted suicide twice. This time was final. He constructed a facemask with polythene and through an ingenious self-closing tube made also from polythene, inhaled ethyl chloride vapor probably after his noonday meal. A man from the village came as usual to offer the evening dana of fluids at about 4 p.m. He tapped the door. There was no response. He then opened it and went into the room. Ñanavira was 'sleeping' on his bed in the position adopted by the Buddha – the lion's pose – with a polythene mask over the face. One hand was fallen with the empty ethyl chloride vial gently laid on the floor. Ñanavira Thera was dead. He ran to the village and the news spread like fire. The whole village, including women and little children ran to the kuti.

The village headman's mother gave a moving graphic account of the funeral arrangements – how she and other women gave their best saris to drape the pyre 8 feet high made by the villagers. Her daughters joined to say that even now Ñanavira is not forgotten. Questions are set about his life at the regional Dhamma Sunday School competitions. My father attended the inquest. There was a sealed letter addressed to the coroner and no postmortem examination was done. The people of Bundala cremated their beloved Ñanavira Thera and interned his ashes by the kuti, beside his sanctuary by the sea.

The ashes of an American monk Nanasumana (Mike Schoen) who died from a bite of a polonga lie beside it now. He had met Ven. Ñanavira in October 1963 and begun regular Dhamma study with him. In a letter to a friend dated 9 Oct. 1964 Nanasumana wrote of Ñanavira: “This is an old man of 60. He is in constant physical pain but he never shows it nor does the peace in his eyes ever change. We spend many hours talking – rather he speaks and I learn”. Note that in 1964. Ven. Ñanavira was only 44 years old. From this brief eyewitness account one can see the harsh physical effects of the bowel disorder. A friend in Yugoslavia sent me this information and a photograph of Ñanavira taken at this time. I am shocked to see the gaunt, emaciated frame of a man who looked like the statue of the Buddha when I knew him. But I too can see the same haunting kindness in his eyes as when I knew him.

Serpents never harmed Ñanavira.

They would uncoil, move some distances and watch him pass. No wild elephant ever threatened him. They would visit the kuti every night, drink the water he leaves in a bucket, sometimes kicking it, and pull his towels and robes on the clothes line to tease him. But they never touched a tile. With one kick, they could demolish the kuti in a minute. So it stands today – and yes, the elephants still keep vigil. Because of Kate I now know more about the kalyanamitra I had. The following year I met her at the Tate Gallery, and she presented me a brand new copy of 'Clearing the Path', the book by Ñanavira Thera on Dhamma that has not been written for 2000 years, reviewed in London as the 'most important book of the century'. He lives in the hearts of people who have no need to understand any of it. Ñanavira, attained sotapatti in 1959, and perhaps arahant at death. He is the legend of Bundala.

[Condensed from the 'A Gist of Dhamma' by the writer]

Existence, Enlightenment and Suicide

Stephen Batchelor

This essay on the English Buddhist monk Ven. Nanavira Thera (Harold Musson) was first published in Tadeusz Skorupski (ed.) The Buddhist Forum. Volume 4. London: School of Oriental and African Studies, 1996.

The Dilemma of Nanavira Thera

"The Buddha's Teaching is quite alien to the European tradition, and a European who adopts it is a rebel."

- Nanavira Thera (1964)[1]

In the early 1960's Somerset Maugham encouraged his nephew Robin to expand his horizons and go to Ceylon: "Find that rich Englishman who is living in a jungle hut there as a Buddhist monk,"[2] he suggested. An aged and somewhat embittered man living alone in a luxurious villa on the Riviera, Maugham's interest in a Westerner who had renounced a life of comfort to live as a hermit in Asia reflected an earlier fascination with the American Larry Darrell, the fictional hero of his novel The Razor's Edge.

Traumatised by his experiences of active service in the First World War, the young Larry Darrell returns home to an affluent and privileged society now rendered hollow and futile. The subsequent events of the novel unfold through the urbane and jaded eyes of Maugham himself, a narrator who assumes a haughty indifference to Larry's existential plight while drawn to him by an anguished curiosity.

Late one night in a café Larry tells Maugham how the shock of seeing a dead fellow airman, a few years older than himself, had brought him to his impasse. The sight, he recalls, "filled me with shame."[3] Maugham is puzzled by this. He too had seen corpses in the war but had been dismayed by "how trifling they looked. There was no dignity in them. Marionettes that the showman had thrown into the discard."[4]

Having renounced a career and marriage, Larry goes to Paris, where he lives austerely and immerses himself in literature and philosophy. When asked by his uncomprehending fiancée why he refuses to come home to Chicago, he answers, "'I couldn't go back now. I'm on the threshold. I see vast lands of the spirit stretching out before me, beckoning, and I'm eager to travel them.'"[5]

After an unsatisfying spell in a Christian monastery Larry finds work as a deckhand on a liner, jumps ship in Bombay and ends up at an ashram in a remote area of South India at the feet of an Indian swami. Here, during a retreat in a nearby forest, he sits beneath a tree at dawn and experiences enlightenment. "'I had a sense,'" he tells Maugham, 'that a knowledge more than human possessed me, so that everything that had been confused was clear and everything that had perplexed me was explained. I was so happy that it was pain and I struggled to release myself from it, for I felt that if it lasted a moment longer I should die.'[6]

The final glimpse we have of Larry is as he prepares to board ship for America, where he plans to vanish among the crowds of New York as a cab-driver. "My taxi," he explains, "[will] be merely the instrument of my labour. ... an equivalent to the staff and begging-bowl of the wandering mendicant."[7]

Maugham's story works insofar that it reflects an actual phenomenon: Western engagement with Eastern traditions in the wake of the First World War. Larry's anonymous return to America likewise bears a prophetic ring. But the novel fails in the author's inability to imagine spiritual experience as anything other than a prolonged mystical orgasm. The sincerity and urgency of Larry's quest is trivialised, and his final resolve fails to carry conviction.

The handful of Westerners who actually travelled to Asia in the first half of the 20th century in search of another wisdom had to leave behind not only the security of their traditions but also the non-commital Romanticism of Somerset Maugham. For the first time in nearly two thousand years, they were preparing to embrace something else. And this step was of another order than either the intellectual enthusiasms of a Schopenhauer or the muddled fantasies of a Blavatsky.

So, at his uncle's behest, Robin Maugham, an investigative journalist, novelist, travel writer and defiantly outspoken homosexual, set off on what he would later describe as his "Search for Nirvana." Six weeks later, around New Year 1965, he arrived in Ceylon. At the Island Hermitage, founded in Dodanduwa in 1911 by the German Nyanatiloka, the doyen of Western Buddhist monks, he was directed to the town of Matara in the extreme south. From Matara Maugham was driven by jeep to the village of Bundala, where the farmers led him to a path that disappeared into the forest. "It was very hot," he recalled, "I could feel the sweat dripping down me. The path became narrower and darker as it led further into the dense jungle." He came to a clearing in which stood a small hut. As he approached, "a tall figure in a saffron robe glided out on to the verandah."[8]

The gaunt man stared at me in silence. He was tall and lean with a short beard and sunken blue eyes. His face was very pale. He stood there, motionless, gazing at me.

"Would you care to come in?" he asked.

His voice was clear with a pleasantly cultured intonation about it; it was calm and cool yet full of authority. He might have been inviting me in for a glass of sherry in his rooms at Cambridge.

Harold Edward Musson was born in Aldershot barracks in 1920. From the age of seven to nine he had lived in Burma, where his father commanded a battalion. He remembered asking someone: "Who was the Buddha?" and being told: "The Buddha was a man who sat under a tree and was enlightened."[9] From that moment he decided that this was what he wanted to do. He was educated at Wellington College and went up to Magdalene College, Cambridge, in 1938, where he read mathematics and then modern languages. It was during this time that he "slowly began to realise that ... I would certainly end my days as a Buddhist monk."[10] He nonetheless volunteered for the army in 1940 and became an officer in Field Security, first in Algiers and later in Italy. His task was to interrogate prisoners of war. In 1945 he was hospitalised in Sorrento and became absorbed in a book on Buddhism called La Dottrina del Risveglio ("The Doctrine of Awakening") by the Italian Julius Evola.

Julius Cesare Andrea Evola was born to a devout Catholic family in Rome in 1898. Having served in a mountain artillery regiment during the First World War, he found himself (like his fictional counterpart Larry Darrell) incapable of returning to normal life. He was overcome with "feelings of the inconsistency and vanity of the aims that usually engage human activities."[11] In response, he became an abstract painter involved in the Dadaist movement and a friend of the founding figure, the Rumanian Tristan Tzara. But by 1921 he became disillusioned with the Dadaist project of "overthrowing all logical, ethical and aesthetic categories by means of producing paradoxical and disconcerting images in order to achieve absolute liberation."[12] He finally rejected the arts as inadequate to the task of resolving his spiritual unrest and after 1922 produced no further poems or paintings.

A further response to his inner crisis was to experiment with drugs through which he attained "states of consciousness partially detached from the physical senses, ... frequently approaching close to the sphere of visionary hallucinations and perhaps also madness."[13] But such experiences only aggravated his dilemma by intensifying his sense of personal disintegration and confusion to the point where he decided, at the age of twenty-three, to commit suicide.

He was only dissuaded from carrying this out by coming across a passage from the Middle Length Sayings (Majjhima Nikaya I, 1 [MN 1]) in the Pali Canon where the Buddha spoke of those things with which the disciple committed to awakening must avoid identifying. Having listed the body, feelings, the elements and so on, he concludes:

Whoever regards extinction as extinction, who thinks of extinction, who reflects about extinction, who thinks: "Extinction is mine," and rejoices in extinction, such a person, I declare, does not know extinction.[14]

For Evola this was "like a sudden illumination. I realised that this desire to end it all, to dissolve myself, was a bond - 'ignorance' as opposed to true freedom."[15]

During the early 1920's Evola's interests turned to the study of philosophy and Eastern religion. During this time he came into contact with Arturo Reghini, a high-ranking Mason and mathematician who believed himself to be a member of the Scuola Italica, an esoteric order that claimed to have survived the fall of ancient Rome. Through Reghini Evola was introduced to René Guénon, whose concept of "Tradition" came to serve as "the basic theme that would finally integrate the system of my ideas."[16]

Evola distinguishes two aspects of this concept. Firstly, it refers to "a primordial tradition of which all particular, historical, pre-modern traditions have been emanations." Secondly, and more importantly, Tradition has nothing to do with conformity or routine; it is the fundamental structure of a kind of civilisation that is organic, differentiated and hierarchic in which all its domains and human activities have an orientation from above and towards what is above.[17]

Such civilisations of the past had as their natural centre an elite or a leader who embodied "an authority as unconditional as it was legitimate and impersonal."[18]

It comes as no great surprise, therefore, that Evola strongly identified with the Right and supported the rise of Fascism in both Italy and Germany. Following Reghini he denounced the Church as the religion of a spiritual proletariat and attacked it ferociously in his book Pagan Imperialism (1927). Around the same time he published such titles as Man as Potency and Revolt Against the Modern World, revealing his indebtedness to Nietszche and Spengler. He did not, however, join the Fascist party and looked down upon Mussolini with aristocratic disdain. (Towards the end of his life he declared that he had never belonged to any political party or voted in an election.)

After Hitler came to power, Evola was feted by high-ranking Nazis, his books were translated into German and he was invited to the country to explain his ideas to select aristocratic and military circles. But, as with many of his German admirers, he kept aloof from what he considered the nationalist, populist and fanatic elements of National Socialism. He claims in his autobiography that because of his position as a foreigner from a friendly nation, he was free to present ideas which had they been voiced by a German would have risked imprisonment in a concentration camp. Nonetheless, when Mussolini was overthrown in 1943, Evola was invited to Vienna by a branch of the SS to translate proscribed texts of Masonic and other secret societies.

In the same year The Doctrine of Awakening, Evola's study of Buddhism, was published in Italy. He regarded the writing of this book as repayment of the "debt" he owed to the doctrine of the Buddha for saving him from suicide. The declared aim of the book was to "illuminate the true nature of original Buddhism, which had been weakened to the point of unrecognisability in most of its subsequent forms."[19] The essential spirit of Buddhist doctrine was, for Evola, "determined by a will for the unconditioned, affirmed in its most radical form, and by investigation into that which leads to mastery over life as much as death."[20]

As its sub-title ("A Study on the Buddhist Ascesis") suggests, Evola's aim was to emphasise the primacy of spiritual discipline and practice as the core of Tradition as represented by Buddhism. He condemns the loss of such ascesis in Europe and deplores the pejorative sense the term has assumed. Even Nietszche, he notes with surprise, shared this anti-ascetic prejudice. Today, he argues, the ascetic path appears with the greatest clarity in Buddhism.

Evola bases his arguments on the Italian translations of the Pali Canon by Neumann and de Lorenzo published between 1916 and 1927. Like many of his generation, the Pali texts represented the only true and original source of the Buddha's teaching. He was nonetheless critical of a large body of accepted opinion that had grown up around them.

Renunciation, for example, does not, for Evola, arise from a sense of despair with the world; he maintains that the four encounters of Prince Siddhartha should be "taken with great reserve." For true aryan renunciation is based on 'knowledge' and is accompanied by a gesture of disdain and a feeling of transcendental dignity; it is qualified by the superior man's will for the unconditioned, by the will ... of a man of quite a special 'race of the spirit.'[21]

The bearing of such a person is "essentially aristocratic," "anti-mystical," "anti-evolutionist," upright and "manly." This race of the spirit is united with the "blood ... of the white races who created the greatest civilisations both of the East and the West" - in particular males of warrior stock.

The aryan tradition has been largely lost in the West through the "influence on European faiths of concepts of Semitic and Asiatic-Mediterranean origin."[22] Yet in the East, too, Buddhism has degenerated into Mahayana universalism that wrongly considers all beings to have the potentiality to become a Buddha. As for Buddhism being "a doctrine of universal compassion encouraging humanitarianism and democratic equality,"[23] this is merely one of many "Western misconceptions."

Evola considers the world of his time to be perverse and dysfunctional. "If normal conditions were to return," he sighs, "few civilisations would seem as odd as the present one."[24] He deplores the craving for material things, which causes man entirely to overlook mastery over his own mind. Nonetheless, one who is still an 'aryan' spirit in a large European or American city, with its skyscrapers and asphalt, with its politics and sport, with its crowds who dance and shout, with its exponents of secular culture and of soulless science and so on - amongst all this he may feel himself more alone and detached and nomad than he would have done in the time of the Buddha.[25]

Evola believed that the original Buddhism disclosed through his study revealed the essence of the aryan tradition that had become lost and corrupted in the West. For him aryan means more than "noble" or "sublime," as it was frequently rendered in translations of Buddhist texts. "They are all later meanings of the word," he explains, "and do not convey the fullness of the original nor the spiritual, aristocratic and racial significance which, nevertheless, is preserved in Buddhism."[26] Other "innate attributes of the aryan soul"[27] that are described in Buddhist texts are an absence "of any sign of departure from consciousness, of sentimentalism or devout effusion, or of semi-intimate conversation with a God." Only among some of the German mystics, such as Eckhart, Tauler and Silesius, does he find examples of this spirit in the Western tradition, "where Christianity has been rectified by a transfusion of aryan blood."[28]

Not only does Buddhism display an aryan spirit but, for Evola, it also endorses the superiority of the warrior caste. Brushing aside the Buddha's well-known denunciation of the caste system, Evola notes that "it was generally held that the bodhisatta ... are never born into a peasant or servile caste but into a warrior or brahman caste."[29] He cites several examples where the Buddha makes analogies between "the qualities of an ascetic and the virtues of a warrior."[30] Of all the Mahayana schools the only one he admired was that of Zen, on account of its having been adopted in Japan as the doctrine of the Samurai class.

[1] "The Buddha's Teaching is quite...": Anon, 390.

[2] "Find that rich Englishman...": The People (26/9/65), Anon., 536.

[3] "filled me with shame...": Somerset Maugham, 272.

[4] "how trifling they looked...": Somerset Maugham, 272.

[5] "'I couldn't go back now...": Somerset Maugham, 73-4.

[6] "'I had a sense,...": Somerset Maugham, 298.

[7] "My taxi,...": Somerset Maugham, 307.

[8] "It was very hot,...": Robin Maugham (1), 186.

[9] "Who was the Buddha?...": Robin Maugham (1), 189.

[10] "slowly began to realise...": Robin Maugham (1), 189.

[11] "feelings of the inconsistancy...": Evola (2), 12 (Tr.).

[12] "overthrowing all logical...": Evola (2), 13 (Tr.).

[13] "states of consciousness...": Evola (2), 13 (Tr.).

[14] "Whoever regards extinction...": Evola (2), 13 (Tr.).

[15] "like a sudden illumination...": Evola (2), 14 (Tr.).

[16] "the basic theme that...": Evola (2), 86 (Tr.).

[17] "has nothing to do with conformity...": Evola (2), 86 (Tr.).

[18] "an authority as much...": Evola (2), 86 (Tr.).

[19] "illuminate the true nature...": Evola (2), 138 (Tr.).

[20] "determined by a will...": Evola (2), 138 (Tr.).

[21] "is based on 'knowledge'...": Evola (1), 95.

[22] "blood ... of the white races...": Evola (1), 17.

[23] "a doctrine of universal compassion...": Evola (1), 43.

[24] "If normal conditions were to return...": Evola (1), 135.

[25] "one who is still an 'aryan' spirit...": Evola (1), 129.

[26] "They are all later...": Evola (1), 16.

[27] "innate attributes of the aryan...": Evola (1), 14.

[28] "where Christianity has been rectified...": Evola (1), 17.

[29] "it was generally held...": Evola (1), 20.

[30] "the qualities of an ascetic...": Evola (1), 20.

References:

Anon. [Samanera Bodhesako] (ed.) Clearing the Path: Writings of Nanavira Thera (1960-1965) . Colombo: Path Press, 1987.

Evola, Julius. Tr. Harold Musson. (1) The Doctrine of Awakening: A Study on the Buddhist Ascesis . London: Luzac, 1951.

------. (2) Le Chemin du Cinabre . Milan: Arché-Arktos, 1982.

Maugham, Robin. (1) Search for Nirvana . London: W.H. Allen, 1975.

------. (2) The Second Window . London: Heinemann, 1968.

Maugham, W. Somerset. The Razor's Edge . London: Mandarin, 1990. [First published by Heinemann, 1944.]

Nanavira Thera. The Tragic, the Comic and the Personal . The Wheel Publication no. 339/341. Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society, 1987. [This is comprised of 29 letters, 27 of which are included in Clearing the Path.]

Rawlinson, Andrew. Western Gurus and Enlightened Masters. La Salle, Illinois: Open Court, forthcoming.

Waterfield, R. "Baron Julius Evola and the Hermetic Tradition," Gnosis, no. 14, Winter 1989-90.

Wettimuny, R. G. de S. The Buddha's Teaching: Its Essential Meaning . Sri Lanka: Private edition, 1990. [First published, 1969. Wettimuny was one of Nanavira's correspondents, to whom he dedicated this book. It is regarded by some as a systematic presentation of Nanavira's views.]

Zolla, E. "The Evolution of Julius Evola's Thought," Gnosis , no. 14, Winter 1989-90.

See also the Book Review Evola's "Doctrine of Awakening" on this site.