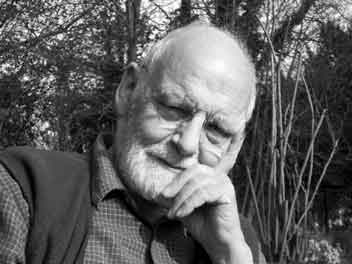

Kenneth Roy Norman. Image courtesy of the Pāḷi Text Society

Kenneth Roy Norman

1925 — 2020

Kenneth Roy Norman was a leading scholar of Middle Indo-Aryan or Prakrit, particularly of Pāli.

Roy or Mr Norman, as he liked to be known, was one of the great scholars of Middle Indo-Aryan philology. His academic career was spent almost entirely in Cambridge. He completed an MA at Cambridge in 1954 and went on to become Lecturer in Indian Studies (1954–1978), then Reader in Indian Studies (1978–1990), before being appointed Professor of Indian Studies in 1990, shortly before his retirement in 1992.

His scholarly contribution to the field of Pāḷi studies has been immense, but his output covered also Jaina studies and the Ashokan inscriptions. His publications include translations of the major verse texts of the Pāḷi canon: Elders’ Verses I (Theragāthā), 1969; Elders’ Verses II (Therīgāthā), 1971; The Group of Discourses (Suttanipāta), 1992, 2nd ed. 2001; The Word of the Doctrine (Dhammapada), 1997; each of these translations includes meticulous philological annotations.

He also published two significant monographs, Pāli Literature (1983) and A Philological Approach to Buddhism (1997; 2nd edition 2006), and leaves behind eight volumes of his Collected Papers (1990–2007). From 1981 to 1990 he was editor of A Critical Pāli Dictionary, overseeing the publication of seven fascicles (11–17) of vol. II.

As well as being a Fellow of the British Academy and a Foreign Member of the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters, he was the longest serving member of the Council of the Pāḷi Text Society (1959–2010) and also served as its President (1981–1994).

It is safe to say that all those who work on ancient texts in middle Indian languages will remain deeply indebted to his work for a long time to come.

Selected Works[1]

Elders' Verses, 2 vols, 1969–71, Pāḷi Text Society: translation of the Theragāthā and Therīgāthā

Pāḷi Literature, Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden, 1983

The Group of Discourses, Pāḷi Text Society: translation of the Suttanipāta

The Word of the Doctrine, Pāḷi Text Society: translation of the Dhammapada

A Philological Approach to Buddhism, SOAS, London; reprinted by Pāḷi Text Society

Pātimokkha, edition and translation with William Pruitt, Pāḷi Text Society

Collected Papers, 8 vols, Pāḷi Text Society

Kankhavitarani with Petra Kieffer-Pülz and William Pruitt, Vol. I, 2019, Vol. 2 in preparation

Notes on the Asokan Rock Edicts, Indo Iranian Journal Vol 10, 1967

A Note on Attā in the Alagaddūpama Sutta, Studies in Indian Philosophy LD Series, 84 - 1981

Pāli Philology and the Study of Buddhism, Seminar Papers 1987–1998, School of Oriental and African Studies 1990

[1] His many articles are in the eight volumes of the Collected Papers.

Selected Quotes from:

A Philological Approach to Buddhism

Used with permission.

p. 11f.

If you examine many translations of Buddhist texts the impression you will gain is that the translator has looked at the words, has perhaps looked them up in the dictionary and has ascertained meanings for them, and then has used his intuition to put those words together to reveal the meaning of the Buddhavacana, the word of the Buddha. Sometimes intuition leads a translator to the right result, and sometimes not.

p. 21

Another way in which philology, the study of why words mean what they do, can be helpful is that we sometimes find that those who made the first English translations of Buddhist texts gave a particular meaning to a word which we have for the most part followed without change ever since. When we come to look at the words themselves we find that the meanings which we have accepted for so long are very often not the only possible meanings but in some cases not even the most likely meanings. Take for example, the phrase “noble truth”, which I mentioned a few minutes ago. It has become a commonplace to talk about the four noble truths, and this is a perfectly acceptable translation of the compound ariya-sacca : ariya means noble and sacca means truth, so ariya-sacca means noble truth. This translation is so common and so fixed in our minds, that it seems almost like blasphemy to have to point out that not only is this not the only possible translation, but it is in fact the least likely of all the possibilities. If we look at the commentators we find that they knew this very well. They point out that the compound can have a number of meanings. It can mean “truth of the noble one”, “truth of the noble ones”, “truth for a noble one”, i.e. truth that will make one noble, as well as the translation “noble truth” so familiar to us. This last possibility, however, they put at the bottom of the list of possibilities, if they mention it at all. My own feeling is that it is very likely that “the truth of the noble one (the Buddha)” is the correct translation, although we must never lose sight of the fact that in Indian literature multiple meanings are very often intended, so that it is not always possible to say that there is a single correct meaning.

p. 27f.

Since I shall in these lectures be giving translations of many of the terms I shall discuss, it would perhaps be sensible to start now by giving some idea of the approach to translation which I have evolved over the years.

It is very difficult to give a one-for-one translation of Sanskrit and Pāli words into English. It is very rare that one Sanskrit or Pāli word has exactly the same connotations, no less and no more, as one English word. This means that if I wish to give a more adequate translation I am forced to give a phrase in English, or perhaps even a whole sentence, or in the case of a very difficult word with a wide range of connotations, even a whole paragraph. Consequently, if I am translating a Buddhist text into English, it is very difficult to produce something which approximates closely to the meaning of the original, and yet appears in good, clear, concise, and readable English.

It is for this reason that many translators do not translate the difficult words, but leave them in their original Sanskrit or Pāli form. And this is fine, for them. As they read through their translations, every time they come across a Sanskrit or a Pā̊li word, they know, within limits, what it means, and they can mentally substitute that meaning. It is not, however, so good for the rest of us, who have little idea of what these scholars have in mind, since their translations may consist of little more than strings of Sanskrit, Pāli or Tibetan words linked together with “ands” and “buts”. Reviewers sometimes complain of translations which are so literal and so full of foreign words that they hardly read as English. Such translations are of little value, and one might just as well leave the whole thing in the original. Only an expert can understand all the words left in the original language, and the expert needs no English words at all.

And so what I have favoured over the years, when translating, is to leave a minimum of these difficult terms in their original form, but the first time they occur, to include a note as lengthy and as detailed as I think is required, giving some idea of what I think the word means, and why I think it means it. In effect I am saying that, every time the reader comes across this word thereafter, he must remember to consult the relevant note to find out what it means in the context. This system does have defects. As anyone who has looked at any of my translations knows, the actual translation is only a small proportion of the book. The notes are far longer, and then there are all the indexes which will enable the reader to find where I dealt first with the problematic word.