The Jātaka:

or

Stories of the Buddha's Former Births

Volume IV

Book 13: Terasa-nipāta

No. 481

Takkāriya-Jātaka[1]

Translated from the Pāli by

W.H.D Rouse, M.A., Sometime Fellow of Christ's College, Cambridge

Under the Editorship of Professor E. B. Cowell

Published 1969 For the Pāli Text Society.

First Published by The Cambridge University Press in 1895

This work is in the Public Domain. The Pali Text Society owns the copyright."

"I spoke," etc. — This story the Master told while dwelling in Jetavana, about Kokālika.

During one rainy season the two Chief Disciples[2], desiring to leave the multitude and to dwell apart, took leave of the Master, and went into the kingdom where Kokālika was. They repaired to the house of Kokālika, and thus said to him: "Brother Kokālika, since for us it is delightful to dwell with you, and for you to dwell with us, we would abide here three months." "How," quoth the other, "will it be delightful for you to dwell with me?" They answered, "If you tell not a soul that the two Chief Disciples are dwelling here, we shall be happy, and that will be our delight in dwelling with you." "And how is it delightful for me to dwell with you?" "We will declare the Law to you three months in your house, and we will discourse to you, and that will be your delight in dwelling with us." "Dwell here, Brethren," quoth he, "so long as you will." and he allotted a pleasant residence to them. There they dwelt in the fruition of the Attainments, and no man knew of their dwelling in that place.

When they had thus past the rains they said to him, "Brother, now we have dwelt with you, and we will go to visit the Master," and asked his leave to go. He agreed, and went with them on the rounds for alms in a village over against the place where they were. After their meal the Elders departed from the village. Kokālika leaving them, turned back and said to the people, "Lay Brethren, you are like brute animals. Here the two Chief Disciples have been dwelling for three months in the monastery opposite, and you knew nothing of it: now they are gone." "Why did you not tell us, Sir?" the people asked. Then they took ghee and oil and simples, raiment and clothes, and approached the Elders, saluting them and saying, "Pardon us, Sirs we knew not you were the Chief Disciples, we have learnt it but to-day by the words of the reverend Brother Kokālika. Pray have compassion on us, and receive these simples and clothes." Kokālika went after the Elders with them, for he thought, "Frugal the Elders are, and content with little; they will not accept these things, and then they will be given to me." But the Elders, because the gift was offered at the instigation of a Brother, neither accepted the things themselves nor had them given to Kokālika. The lay folk then said, "Sirs, if you will not accept these, come hither once again to bless us." The Elders promised, and proceeded to the Master's presence.

Now Kokālika was angry, because the Elders neither accepted those things themselves, nor had them given to him. The Elders, however, having remained a short while with the Master, chose out each five hundred Brethren as their following, and with these thousand Brethren went on pilgrimage seeking alms, as far as Kokālika's country. The lay folk came out to meet them, and led them to the same monastery, and showed them great honour day by day.

Great was the store given them of clothes and of simples. Those Brethren who went out with the Elders dividing the garments gave of them to all the Brethren which had come, but to Kokālika gave none, neither did the Elders give him any. Kokālika getting no clothes began to abuse and revile the Elders: "Sāriputta and Moggallāna are full of sinful desire; they would not accept before what was offered them, but these things they do accept. There is no satisfying them, they have no regard for another." But the Elders, perceiving that the man was harbouring evil on their account, set out with their followers to depart; nor would they return, not though the people begged them to stay yet a few days longer. Then a young Brother said: "Where shall the Elders stay, laymen? Your own particular Elder does not wish them to stay here." Then the people went to Kokālika, and said, "Sir, we are told you do not wish the Elders to stay here. Go to! Either appease them and bring them back, or away with you and live elsewhere!" In fear of the people this man went and made his request to the Elders. "Go back, Brother," answered the Elders, "we will not return." So he being unable to prevail upon them returned to the monastery. Then the lay brethren asked him whether the Elders had returned. "I could not persuade them to return," said he. "Why not, Brother?" they asked. And then they began to think it must be, no good Brethren would dwell there because the man lived in sin; they must get rid of him. "Sir," they said, "do not stay here; we have nothing here for you."

Thus dishonoured by them, he took bowl and robe and went to Jetavana. After saluting the Master, he said, "Sir, Sāriputta and Moggallāna are full of sinful desire, they are in the power of sinful desires!" The Master replied, "Say not so, Kokālika; let your heart, Kokālika, be in charity with Sāriputta and Moggallāna; learn that they are good Brethren." Kokālika said, "You believe in your two Chief Disciples, Sir; I have seen it with my own eyes; they have sinful desires, they have secrets within them, they are wicked men." So he said thrice (though the Master would have stayed him), then rose from his seat, and departed. Even as he went on his way there arose over all his body boils of the size of a mustard seed, grew and grew to the size of a ripe seed of the vilva tree[3], burst, ran blood all over him. Groaning he fell by the gate of Jetavana, maddened with pain. A great cry arose, and reached even to Brahma's world — "Kokālika has reviled the two Chief Disciples!" Then his spiritual teacher, the Brahmā angel, Tudu by name, learning the fact, came with the intent of appeasing the Elders, and said while poised in the air, "Kokālika, a cruel thing this you have done; make your peace with the Chief Disciples." "Who are you, brother?" the man asked. "Tudu Brahmā, is my name," said he. "Have you not been declared by the Blessed One," said the man, "one of those who return not[4]? That word means that such come not back to this earth. You will become a goblin upon a dunghill!" Thus he upbraided the great Brahma angel. And as he could not persuade the man to do as he advised, he replied to him, "May you be tormented according to your own word." Then he returned to his abode of bliss. And Kokālika dying was born again in the Lotus Hell[5]. That he had been born there the great and mighty Brahmā Lord[6] told to the Tathāgata, and the Master told it to the Brethren. In the Hall of Truth the Brethren talked of the man's wickedness: "Brother, they say Kokālika reviled Sāriputta and Moggallāna, and by the words of his own mouth came to the Lotus Hell." The Master came in, and said he, "What speak ye of, Brethren, as ye sit here?" They told him. Then he said, "This is not the first time, Brethren, that Kokālika was destroyed by his own word, and out of his own mouth was condemned to misery; it was the same before." And he told them a story of the past.

Once upon a time, when Brahmadatta was king of Benares, his chaplain was tawny-brown[7] and had lost all his teeth. His wife committed sin with another brahmin. This man was just like the other[8]. The chaplain tried times and again to restrain his wife, but could not. Then he thought, "This my enemy I cannot kill with my own hands, but I must devise some plan to kill him."

So he came before the king, and said: "O king, your city is the chiefest city of all India, and you are the chiefest king: but chief king though you are, your southern gate is unlucky, and ill put together." "Well now, my teacher, what is to be done?" "You must bring good luck into it and set it right." "What is to be done?" "We must pull down the old door, get new and lucky timbers, do sacrifice to the beings that guard the city, and set up the new on a lucky conjunction of the stars." "So do, then," said the king.

At that time, the Bodhisatta was a young man named Takkāriya, who was studying under this man.

Now the chaplain caused the old gate to be pulled down, and the new was made ready; which done, he went and said to the king, "The gate is ready, my lord: to-morrow is an auspicious conjunction; before the morrow is over, we must do sacrifice and set up the new gate." "Well, my teacher, and what is necessary for the rite?" "My lord, a great gate is possessed and guarded by great spirits. A brahmin, tawny-brown and toothless, of pure blood on both sides, must be killed; his flesh and blood must be offered in worship, and his body laid beneath, and the gate raised upon it. This will bring luck to you and your city[9]." "Very well, my teacher, have such a brahmin slain, and set up the gate upon him."

The chaplain was delighted. "To-morrow," said he, "I shall see the back of my enemy!" Full of energy he returned to his home, but could not keep a still tongue in his head, and said quickly to his wife," Ah, you foul hag, whom will you have now to take your pleasure with? Tomorrow I shall kill your leman and make sacrifice of him!" "Why will you kill an innocent man?" "The king has commanded me to slay and sacrifice a tawny-brown brahmin, and to set up the city gate upon him. Your leman is tawny-brown, and I mean to slay him for the sacrifice. "She sent her paramour a message, saying, "They say the king wishes to slay a tawny-brown brahmin in sacrifice; if you would save your life, flee away in time, and with you all they who are like you." So the man did: the news spread abroad in the city, and all those in the whole city who were tawny-brown fled away.

The chaplain, nothing aware of his enemy's flight, went early next morning to the king, and said, "My lord, in such a place is a tawny-brown brahmin to be found; have him taken." The king sent some men for him, but they saw none, and returning informed the king that he was fled away. "Search elsewhere," said the king. All over the city they searched, but found none. "Search quickly!" said the king. "My lord," they replied, "except your chaplain there is no such other." "A chaplain," quoth he, "cannot be killed." "What do you say, my lord? According to the chaplain, if the gate is not set up to-day, the city will be in danger. When the chaplain explained the matter, he said that if we let this day go by, the auspicious moment will not come again until the end of a year. The city without a gate for a year, what a chance for our enemies! Let us kill some one, and sacrifice by the aid of some other wise brahmin, and set up the gate." "But is there another wise brahmin like my teacher?" "There is, my lord, his pupil, a young man named Takkāriya; make him your chaplain and do the lucky ceremony." The king sent for him, and did honour to him, and made him chaplain, and commanded to do as had been said. The young man went to the gate with a great crowd following. In the king's name they bound and brought the chaplain. The Great Being caused a pit to be dug in the place where the gate was to be set up, and a tent to be placed over it, and with his teacher entered into the tent. The teacher beholding the pit, and seeing no escape, said to the Great Being, "My aim had succeeded. Fool that I was, I could not keep a still tongue, but hastily told that wicked woman. I have slain myself with my own weapon." Then he recited the first stanza:

"I spoke in folly, as a frog might call

Upon a snake in the forest: so I fall

Into this pit, Takkāriyā[10]. How true,

Words spoken out of season one must rue!"

Then the other addressing him, recited this stanza:

"The man who out of season speaks, will go

Like this to ruin, lamentation, woe:

Here you should blame yourself, now you must have

This delvèd pit, my teacher, for your grave."

To these words he added yet this: "O teacher, not thou only, but many another likewise, has come to misery because he set not a watch upon his words." So saying, he told him a story of the past to prove it.

Once upon a time, they say, there lived a courtesan in Benares named Kālī, and she had a brother named Tuṇḍila. In one day Kālī would earn a thousand pieces of money. Now Tuṇḍila was a debauchee, a drunkard, a gambler; she gave him money, and whatever he got he wasted. Do what she would to restrain him, restrain him she could not. One day he was beaten at hazard, and lost the very clothes he was clad in. Wrapping about him a rag of loin-cloth, he repaired to his sister's house. But command had been given by her to her serving-maids, that if Tuṇḍila should come, they were to give him nothing, but to take him by the throat and cast him out. And so they did: he stood by the threshould, and made his moan. Now a certain rich merchant's son, who used constantly to give Kālī a thousand pieces of money, on that day happened to see him, and says he, "Why are you weeping, Tuṇḍila?" "Master," said he, "I have been beaten at the dice, and came to my sister; and the serving-maids took me by the throat and cast me out." "Well, stay here," quoth the other, "and I will speak to your sister." He entered the house, and said, "Your brother stands waiting, clad in a rag of loin-cloth. Why do you not give him something to wear?" "Indeed," she replied, "I will give nothing. If you are fond of him, give it yourself." Now in that house of ill fame the fashion was this: out of every thousand pieces of money received, five hundred were for the woman, five hundred were the price of clothes, perfumes and garlands; the men who visited that house received garments to clothe themselves in, and stayed the night there, then on the next day they put off the garments they had received, and put on those they had brought, and went their ways. On this occasion the merchant's son put on the garments provided for him, and gave his own clothes to Tuṇḍila. He put them on, and with loud shouts hastened to the tavern. But Kālī ordered her women that when the young man should depart next day, they should take away his clothes. Accordingly, when he came forth, they ran up from this side and that, like so many robbers, and took the clothes from him, and stript him naked, saying, "Now, young sir, be off!" Thus they got rid of him. Away he went naked: the people made sport of him, and he was ashamed, and lamented, saying, "It is my own doing, because I could not keep watch over my lips!" To make this clear, the Great Being recited the third stanza:

"Why ask of Tuṇḍila how he should fare

At Kālikā his sister's hands? now see!

My clothes are gone, naked am I and bare;

'Tis monstrous like what happened late to thee."

Another person relates this story. By carelessness of the goat herds, two rains fell a-fighting on a pasture at Benares. As they were hard at it, a certain fork-tail thought to himself, "These two will crack their polls and perish; I must restrain them." So he tried to restrain them by calling out — "Uncle, don't fight!" Not a word he got from them: in the midst of the battle, mounting first on the back, then on the head, he besought them to stop, but could do nothing. At last he cried, "Fight, then, but kill me first!" and placed himself between the two heads. They went on butting away at each other. The bird was crushed as by a pounder, and came to destruction by his own act. To explain this other tale the Great Being repeated the fourth stanza:

"Between two fighting rams a fork-tail flew,

Though in the fray he had no part nor share.

The two rams' heads did crush him then and there.

He in his fate was monstrous like to you!"

Another. There was a tal-tree which the cowherds set great store by. The people of Benares seeing it sent a certain man up the tree to gather fruit. As he was throwing down the fruit, a black snake issuing forth from an anthill began to ascend the tree; they who stood below tried to drive him off by striking at him with sticks and other things, but could not. Then they called out to the other, "A snake is climbing the tree!" and he in terror uttered a loud cry. Those who stood below seized a stout cloth by the four corners, and bade him fall into the cloth. He let himself drop, and fell in the midst of the cloth between the four of them; swift as the wind he came, and the men could not hold him, but jolled their four heads together and broke them, and so died. To explain this story the Great Being recited the fifth stanza:

"Four men, to save a fellow from his fate,

Held the four corners of a cloth below.

They all fell dead, each with a broken pate.

These men were monstrous like to you, I trow."

Others again tell this. Some goat-thieves who lived at Benares having stolen a she-goat one night, determined to make a meal in the forest: to prevent her bleating they muffled her snout and tied her up in a bamboo clump. Next day, on their way to kill her, they forgot the chopper. "Now we'll kill the goat, and cook her," said they; "bring the chopper here!" But nobody had one. "Without a chopper," said they, "we cannot eat the beast, even if we kill her: let her go! this is due to some merit of hers." So they let her go. Now it happened that a worker in bamboos, who had been there for a bundle of them, left a basket-maker's knife there hidden among the leaves, intending to use it when he came again. But the goat, thinking herself to be free, began playing about under the bamboo clump, and kicking with her hind legs made the knife drop. The thieves heard the sound of the falling knife, and on coming to find out what it was, saw it, to their great delight; then they killed the goat, and ate her flesh[11]. Thus to explain how this she-goat was killed by her own act, the Great Being recited the sixth stanza:

"A she-goat, in a bamboo thicket bound,

Frisking about, herself a knife had found.

With that same knife they cut the creature's throat.

It strikes me you are monstrous like that goat."

After recounting this, he explained, "But they who are moderate of speech, by watching their words have often been freed from the fate of death," and then told a story of fairies[12].

A hunter, we are told, who lived in Benares, being once in the region of Himalaya, by some means or other captured a brace of supernatural beings, a nymph and her husband; and them he took and presented to the king. The king had never seen such beings before. "Hunter," quoth he, "what kind of creatures are these?" Said the man, "My lord, these can sing with a honey-voice, they dance delightfully: no men are able to dance or sing as they can." The king bestowed a great reward on the hunter, and commanded the fairies to sing and dance. But they thought, "If we are not able to convey the full sense of our song, the song will be a failure, they will abuse and hurt us; and then again, those who speak much speak falsely:" so for fear of some falsehood or other they neither sang nor danced, for all the king begged them again and again. At last the king grew angry, and said, "Kill these creatures, and cook them, and serve them up to me." This command he delivered in the words of the seventh stanza:

"No gods are these nor heaven's musicianers[13],

Beasts brought by one who fain would fill his purse.

So for my supper let them cook me one,

And one for breakfast by the morrow's sun."

Then the fairy-dame thought to herself," Now the king is angry; without doubt he will kill us. Now it is time to speak."And immediately she recited a stanza:

"A hundred thousand ditties all sung wrong

All are not worth a tithe of one good song.

To sing ill is a crime; and this is why

(Not out of folly) fairy would not try."

The king, pleased with the fairy, at once recited a stanza:

"She that hath spoken, let her go, that she

The Himalaya hill again may see,

But let them take and kill the other one,

And for to-morrow's breakfast have him done."

But the other fairy thought, "If I hold my tongue, surely the king will kill me; now is the time to speak;" and then he recited another stanza:

"The kine depend upon the clouds[14], and men upon the kine,

And I, O king! depend on thee, on me this wife of mine.

Let one, before he seek the hills, the other's fate divine."

When he had said this, he repeated a couple of stanzas, to make it clear, that they had been silent not from unwillingness to obey the king's word, but because they saw that speaking would be a mistake.

"O monarch! other peoples, other ways:

'Tis very hard to keep you clear of blame.

The very thing which for the one wins praise,

Another finds reproof for just the same.

"Some one there is who each man foolish finds[15];

Each by imagination different still;

All different, many men and many minds,

No universal law is one man's will."

Quoth the king, "He speaks the truth; 'tis a sapient fairy;" and much pleased he recited the last stanza:

"Silent they were, the fairy and his mate:

And he who now did utter speech for fear,

Unhurt, free, happy, let him go his gait.

This is the speech brings good, as oft we hear."

Then the king placed the two fairies in a golden cage, and sending for the huntsman, made him set them free in the same place where he had caught them.

The Great Being added, "See, my teacher! In this manner the fairies kept watch on their words, and by speaking at the right time were set free for their well speaking; but you by your ill speaking have come to great misery." Then after showing him this parallel, he comforted him, saying, "Fear not, my teacher; I will save your life." "Is there indeed a way," asked the other, "how you can save me?" He replied, "It is not yet the proper conjunction of the planets." He let the day go by, and in the middle watch of the night brought thither a dead goat. "Go when you will, brahmin, and live," said he, then let him go and never a soul the wiser. And he did sacrifice with the flesh of the goat, and set up the gate upon it.

When the Master had ended this discourse, he said: "This is not the first time, Brethren, that Kokālika was destroyed by his own words, but it was the same before;" after which he identified the Birth: "At that time Kokālika was the tawny-brown man, and I myself was the wise Takkāriya."

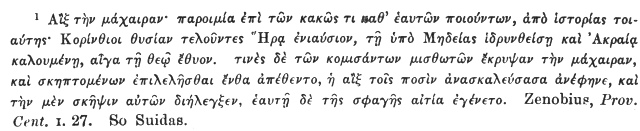

[1] See L. Feer in Journal Asiatique, ix. Ser., xi. 189 ff. Compare also Zeitschr. der deutsch. morg. Gesellschaft, xlvii. 86, on αἲξ μάχαιραν.

[2] Sāriputta and Moggallāna.

[3] Aegle Marmelos.

[4] Anāgāmi, those of the Third Path, who return not to be reborn on earth.

[5] Not in Hardy's list of the chief Hells (Manual, p. 26); but there were 136 of them. Burnouf gives it, Introd. p. 201.

[6] Sahampati; the meaning of the first part is unknown; he is the chief of the Brahma Heaven, of which Tudu is an angel.

[7] Piṇgalo is not a proper name; see p. 246. 6 (Pāli).

[8] A full stop should be placed at va. As printed, this sentence is unintelligible.

[9] Human sacrifice at the founding of a building, or the like, must have been common in ancient times, so persistent are the traditions about it. For India, see Crooke, Intr. to Pop. Rel. and F.-L. of N. India, p. 237 and Index. When the Hooghly Bridge was built in Calcutta, I remember how it was commonly said by the natives that the builders had immured many young children in the foundations. For Greece it is attested by modern folk-songs such as the Bridge of Arta (Passow, Carm. Pop. Gr. no. 512), and one which I lately wrote down in Cos from oral tradition (published in Folk-Lore for 1899). The sacrifice is meant to propitiate the spirits disturbed by the digging. See Robertson Smith, Religion of the Semites, p. 158.

[10] The name here is feminine, as the scholiast notes without explanation.

[11]

Zenobius, Prov. Cent. I. 27. So Suidas.

[12] kinnarā.

[13] gandhabbaputtā.

[14] Because their food (grass etc.) depends on rain.

[15] Reading paracitte: "everybody is foolish in some other man's opinion." In line 2, there may be a pun on citto (various): "all the world becomes different through the power of thought."