PSALMS OF THE SISTERS

XIX

Abhirūpa-Nandā

Born in the time of the Buddha Vipassi, in his native town of Bandhumati, as the daughter of a wealthy burgess, she became a pious lay-adherent, and at the Master's death she made an offering to the shrine of his ashes of a golden umbrella[1] surrounded with jewels. Reborn for this in various heavens, she was, in this Buddha-dispensation, reborn at Kapilavatthu as the daughter of the chief wife of Khemaka, the Sākiyan, and named Nanda. But because of her excessive beauty, charm, and loveliness, she was known as Nanda the Fair.

Now, on the day when she was to choose among her suitors,[2] Carabhuta, her young Sākiyan kinsman, died. Then her parents made her leave the world against her will. But she, even after she had entered the Order, was infatuated with her own beauty, and, fearing the Master's rebuke, avoided his presence. Now the Exalted One knew that she was ripe for knowledge, and directed the Great Pajajati to let all the Bhikkhunīs come to him for instruction. Nanda sent another in her place. And the Exalted [23] One said, 'Let no one come by proxy.' So she was compelled to come. And the Exalted One, by his mystic power, conjured up a beautiful woman, and showed her becoming aged and fading, causing anguish to arise in Nanda. And he addressed her in these words:

[19] Behold, Nanda, the foul compound, diseased,

Impure! Compel thy heart to contemplate

What is not fair to view. So steel thyself

And concentrate the well-composèd mind.

[20] That ponder where no Threefold Sign[3] is seen.

Cast out the baneful bias of conceit.

Hath the mind mastered vain imaginings,[4]

Then mayst thou go thy ways, calm and serene.

And when he had finished speaking, she attained Arahantship. Repeating to herself the verses, she made them the announcement of her aññā.

XX

Jentī or Jentā

The story of her past and present is like that of Nandā the Fair; but it was at Vesalī, in the princely family of the Licchavis, that she was reborn.[5] There is this further difference: she attained Arahantship after hearing the Master preach the Dhamma, and it was when reflecting on the change that had come over her that she, in joy, uttered these verses:

[24] [21] The Seven Factors of the awakened mind[6] —

Seven ways whereby we may Nibbāna win —

All, all have I developed and made ripe,

Even according to the Buddha's word.

[22] For I therein have seen as with mine eyes

The Bless'd, the Exalted One.[7] Last of all lives

Is this that makes up Me. The round of births

Is vanquishèd — Ne'er shall I be again!

XXI

Sumangala's Mother

She, too, having made her resolve under former Buddhas, and heaping up good in this rebirth and that, was born under this Buddha-dispensation in a poor family at Sāvatthī, and was married to a rush-plaiter. Her firstborn was a son, come for the last time to birth, who grew up to become the Elder Sumangala and an Arahant.[8] And her name not becoming known, she was called in the Pali text a certain unknown Therī, and is known as Sumangala's mother. She became a Bhikkhunī, and one day, while reflecting on all she had suffered as a laywoman, she was much affected, and, her insight quickening, [25] she attained Arahantship, with thorough knowledge of the form and meaning of the Dhamma. Thereupon she exclaimed:

[23] O woman well set free! how free am I,[9]

How throughly free from kitchen drudgery!

Me stained and squalid 'mong my cooking-pots

My brutal husband ranked as even less

Than the sunshades he sits and weaves alway.[10]

[24] Purged now of all my former lust and hate,

I dwell, musing at ease beneath the shade

Of spreading boughs — O, but 'tis well with me!

XXII

Aḍḍhakāsī

Born of a respectable family, in the time of Kassapa Buddha, she won understanding, and became a Bhikkhunī, established in the precepts. But she reviled an Arahant Elder Sister by calling her a prostitute,[11] and for this she went to purgatory. In this Buddha-dispensation she was [26] reborn in the kingdom of Kāsī as the child of a distinguished and prosperous citizen. But because of the persistent effect of her former evil speech, she became herself a prostitute. How she left the world and was ordained by special messenger is related in the Culla Vagga.[12] For she wished to go to Sāvatthī to be ordained by the Exalted One. But the libertines of Benares barred the ways, so she sent and asked the Exalted One's advice, and he permitted her to be ordained by a messenger. Then she, working at insight, not long after obtained Arahantship, with thorough knowledge of the Dhamma in form and meaning. Thereupon she exclaimed:

[25] No less my fee was than the Kāsī realm

Paid in revènue — this was based on that,

Value for value, — so the sheriff fixed.

[26] But irksome now is all my loveliness;

I weary of it, disillusionized.

Ne'er would I more, again and yet again,

Run on the round of rebirth and of death!

Now real and true for me the Triple Lore.[13]

Accomplished is the bidding of the Lord.

XXIII

Cittā

She, too, having made her resolve under former Buddhas, and heaping up good of age-enduring efficacy in this rebirth and that, was born in the 94th æon[14] as a fairy. She worshipped with offering of flowers a Silent (Pacceka) Buddha.[15] And after many other births among men and gods, she was, in this Buddha-dispensation, born at Rājagaha in the family of a leading burgess. When she had come to years of discretion she heard the Master teaching at the gate of Rājagaha, and, becoming a believer, she was ordained by the Great Pājapatī the Gotamid. And at length, in her old age, when she had climbed the Vulture's Peak, and had done the exercises of a recluse, her insight expanded, and she won to Arahantship. Reflecting thereon, she gave utterance as follows:

[27] Though I be suffering and weak, and all

My youthful spring be gone, yet have I climbed,

Leaning upon my staff, the mountain crest.

[28] Thrown from my shoulder hangs my cloak, o'erturned

My little bowl. So 'gainst the rock I lean

And prop this self of me, and break away

The wildering gloom that long had closed me in.

XXIV

Mettikā

Heaping up merit under former Buddhas, she was born during the time of Siddhattha,[16] the Exalted One, in a burgess's family, and worshipped at his shrine by offering there a jewelled girdle. After many births in heaven and on earth, through the merit thereof, she became, in this Buddha-dispensation, the child of an eminent brahmin at Rājagaha. In other respects her case is like the preceding one, save that it was another hill corresponding to Vulture's Peak up which she climbed.[17]

She, too, reflecting on what she had won, said in exultation:

[29] Though I be suffering and weak, and all

My youthful spring be gone, yet have I come,

Leaning upon my staff, and clomb aloft

The mountain peak.

[30] My cloak thrown off,

My little bowl o'erturned: so sit I here

Upon the rock. And o'er my spirit sweeps

The breath[18] of Liberty! I win, I win

The Triple Lore! The Buddha's will is done!

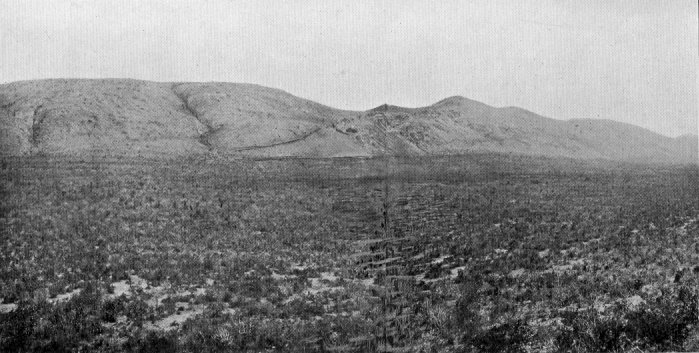

Vulture Peak Range above Old Rājagaha.

XXV

Mittā[19]

Born in the time of Vipassi Buddha of a noble family, and become a lady of his father's court, she won meritorious karma by bestowing food and precious raiment on an Arahant Elder Sister.[20] Born finally, in this Buddha-dispensation, in the princely family of the Sākiyas, at Kapilavatthu, she left the world together with Great Pājapatī the Gotamid, and, going through the requisite training for insight, not long after won Arahantship.

Reflecting thereon, joy and gladness stirred her to say:

[31] On full-moon day and on the fifteenth day,

And eke the eighth of either half the month,

I kept the feast; I kept the precepts eight,

The extra fasts,[21] enamoured of the gods,

And fain to dwell in homes celestial.

[32] To-day one meal, head shaved, a yellow robe —

Enough for me. I want no heaven of gods.

Heart's pain, heart's pining, have I trained away.

XXVI

Abhaya's Mother

Heaping up merit under former Buddhas, she, in the time of Tissa Buddha,[22] saw him going round for alms, and with glad heart took his bowl and placed in it a spoonful of food. Reborn for that among gods and among men, she was born also for that, in this Buddha-dispensation, and became the town belle of Ujjenī, by name Padumavatī.[23] And King Bimbisāra (of Magadha) heard of her, and expressed to his chaplain the wish to see her. By the power of his spells, the chaplain summoned a Yakkha who, by his might, brought the King to Ujjenī. And when she afterwards sent word to the King that she was with child by him, he sent back word, saying: 'If it be a son, let me see him when he is grown.' And she bore a son and called him Abhaya. When he was seven years old she told him who was his father, and sent him to Bimbisāra. The King loved the boy, and let him grow up with the boys of his court. His conversion and ordination is told in the Psalms of the Elders.[24] And, later on, his mother heard her son preach the Dhamma, and she, too, left the world and afterwards attained Arahantship, with thorough grasp of the Dhamma in form and meaning. She thereupon recalled and repeated the verse wherewith her son had admonished her, and added her own thereto:

[33] 'Upward from sole of foot, O mother dear,

Downward from crown of hair this body see.

Is't not impure, the evil-smelling thing?'

[34] This have I pondered. meditating still,

Till every throb of lust is rooted out.

Expunged is all the fever of desire.

Cool am I now and calm — Nibbāna's peace.

XXVII

Abhayā[25]

She, too, having made her resolve under former Buddhas, and heaping up merit of age-enduring efficacy in this and that state of becoming, was, in the time of Sikhi Buddha,[26] reborn in a great noble's family, and became the chief queen of his father Aruṇa. And one day she worshipped the Exalted One with offering of red lotuses given her by the King, when Sikhi Buddha, at alms-time, entered the palace. Reborn for this among gods and men, she was, in this Buddha-dispensation, born once more at Ujjenī in a respectable family, and became the playmate of Abhaya's mother. And when the latter had left the world, Abhayā, for love of her, also took orders. Dwelling with her at Rājagaha, she went one day to Cool-Grove to contemplate on a basis of some foul thing.[27] The Master, seated in his Fragrant Chamber, caused her to see before her the kind of object she had been directed to choose. Seeing the vision, dread seized her. Then the Master, sending forth glory, appeared as if seated before her, and said:

[35] Brittle, O Abhayā, the body is,

Whereto the worldling's happiness is bound.

For me I shall lay down this mortal frame,

Mindful and self-possessed in all I do.

[36] For all my heart was in the work whereby

I struggled free from all that breedeth Ill.

[32] Craving have I destroyed, and brought to pass

That which the Buddhas have revealed to men.[28]

And when he had finished speaking she attained Arahantship. Exulting herein, she turned the verses round into an address to herself.

XXVIII

Sāmā

She, too, having made her resolve under former Buddhas, and heaping up good of age-enduring efficacy in this and that state of becoming, being reborn in fortunate conditions, took birth, in this Buddha-dispensation, at Kosambī, in the family of an eminent burgess. When her dear friend, the lay-disciple Sāmāvatī, died, she, in her distress, left the world. But being unable to subdue her grief for her friend, she was unable to grasp the Ariyan Way. Now, while she was seated in the sitting-room, listening to Elder Ānanda preaching, she was established in insight, and, on the seventh day after, attained Arahantship, with thorough grasp of the Dhamma in form and meaning.

And reflecting on what she had won, she expressed it in this psalm:

[37] Four times, nay, five, I sallied from my cell,

And roamed afield to find the peace of mind

I sought in vain, and governance of thoughts

I could not bring into captivity.[29]

[33] [38] To me, even to me, on that eighth day

It came: all craving ousted from my heart.

'Mid many sore afflictions, I had wrought

With passionate endeavour, and had won!

Craving was dead, and the Lord's will was done.

[1] Or tee, surmounting the cupola. Vipassi was the first of the seven Buddhas of the Pitakas.

[2] I read vāreyyadivase (cf. p. 276, verse 464), which makes sense anyway. It would appear that Carabhūta (pronounced Chāraā) would have been the object of her choice.

[3] Animittaṇ, ideals not depending on what is impermanent, or on what makes for sorrow, or on the presence of a persisting soul-entity (Rhys Davids, Yogāvacara's Manual, xxvi., xxviii.).

[4] Māna, conceit, pride, vanity, one of the seven forms of bias. Majjh. Nik., i. 109, 110; Vibh., 340. Translator's Buddh. Psy., 298, n. 3.

[5] Cf. Rhys Davids, Buddhist India, 25, 40.

[6] The Bojjhangas or Sambojjhangas; lit., parts or limbs of Bodhi. They were mindfulness, research in the Dhamma, energy, joy, serenity, concentration, equanimity (B. Psy., 84, n. 2. Cf. Ps. xxxi.).

[7] 'For inasmuch as the Exalted One is the very Body of the Norm, to discern the Ariyan Dhamma which is His is to see Him. The Buddhas and other Ariyans are said to be seen, not only by the sight of their visible shape, but also by insight into the Ariyan Dhamma, according as He said: "Verily, Vakkhali, he that seeth the Norm, he seeth me"' (Sa.yutta Nikaya, iii., p. 120). '"The Ariyan disciple who hears, brethren, is one who sees the Ariyans"' (Commentary).

[8] This is the Elder Sumangala, who in his verse (Theragāthā, 43) celebrates his release from three 'crooked things' (supra, Ps. xi.) — rom sickle, plough, and spade.

[9] Expressed in the text by the representative drudgery of the 'mortar' (musala).

[10] In the Pali the first two lines depart from the √loka metre, being apparently a curious variety of some metre I cannot identify. See Introduction. The last two lines revert to the √loka, sukhato being an obvious gloss. Quite literally, the quaint and elliptical passage runs: 'The shameless one me "sunshade" only,' which the Commentary explains as 'My husband calls me not even an umbrella which he makes for his livelihood.' There seems nothing in verses or Commentary to justify Dr. Neumann's inference that her husband lived on her adulterous earnings. Toil has spoilt her looks, and he takes no further pleasure in them.

[12] Vinaya Texts (S.B.E. xx.), ii., p. 360. (Pronounced 'Chul'la.') Benares was the capital of Kāsī. On the name Aḍḍha Kāsī (lit., half-Kāsī), see op. cit., ii. 195, n. 2.

[13] Tisso vijjā. The Brahmanic phrase, tevijjo, often recurring below — e.g., Ps. xxxvi. — and signifying 'versed in the three Vedas,' was, according to Aṇguttara-Nikaya, i. 163-5, adopted by the Buddha and applied to the three attainments of paññā, entitled reminiscence of former births, the Heavenly Eye, and the destruction of the Asavas.

[14] I.e., before this present age.

[16] One of the (later elaborated) twenty-four Buddhas.

[17] Rājgir (the ancient burg) is surrounded by some seven hills. See Cunningham's Archaeological Survey, ii., Pl. xli.

[18] Lit., 'Now is my heart (or mind) set free!' For lovers of the mountain, the 'great air' and the sense of spiritual freedom will be tightly bound up. The age of the two climbers throws into relief the arduousness of their spiritual ascent.

[19] Mettā in the Commentary. Mittā = amica. Cf. Ps. viii. Both Mitta and Mettika (Ps. xxiv.) may be patronymics, derived ultimately from Mitra (Mithra), the Vedic propitious, friendly Day or Sun god.

[20] In the Apadāna it is 'a religieux' of no specified Order.

[21] See Rhys Davids, Buddhism, 139-141.

[22] One of the twenty-four.

[23] I.e., she of the Lotus.

[24] Abhaya's verses (Th., 26, 98) do not refer to his mother.

[25] Fearless.

[26] Second of the Seven Buddhas.

[27] B. Psy., p. 69. The 'foul things' were corpses or human bones, such as might be seen in any charnel field, where the dead were exposed and not cremated. I have before me a photograph of a Ceylonese bhikkhu seated in the cleft of a rock contemplating two skulls and other bones lying before him — a modern snapshot of a scene that might be 2,500 years old instead of 250 days.

[28] Lit. (as in many other verses), 'done is the will, or rather the system or teaching (sāsanaṃ) of the Buddha.' Verses 36, 38, and 41 (except the last two lines) are in the text identical, though varied in translation.

[29] Cf. 2 Cor. x. 5.