PSALMS OF THE SISTERS

L

Paṭācārā's Five Hundred[1]

THESE too, having fared under former Buddhas as the foregoing Sisters, were, in this Buddha-era, reborn in some clansman's house in divers places, were married, and bore children, living domestic lives. And having wrought karma such as would bring to pass such a result, they suffered bereavement in the death of a child. Then they found their way, overwhelmed with grief, to Paṭācārā, and saluting her, and seated by, her, told her the manner of their sorrow. The Sister, restraining their sorrow, spake thus:

[127] The way by which men come we cannot know;

Nor can we see the path by which they go.

[78] Why mournest then for him who came to thee,

Lamenting through thy tears: 'My son! my son!'

[128] Seeing thou knowest not the way he came,

Nor yet the manner of his leaving thee?

Weep not, for such is here the life of man.

[129] Unask'd he came, unbidden went he hence.

Lo! ask thyself again whence came thy son

To bide on earth this little breathing space?

[130] By one way come and by another gone,

As man to die, and pass to other births —

So hither and so hence — why would ye weep?[2]

They, hearing her doctrine, were filled with agitation, and, under the Therī, renounced the world. Exercising themselves henceforth in insight, their faculties growing ripe for emancipation, they soon became established in Arahantship, with thorough grasp of the Norm in form and in meaning. Thereafter, pondering on their attainment, they exulted in those words, 'The way by which men come,' adding thereto other verses, and repeating them in turn, as follows:

[131] Lo! from my heart the hidden shaft is gone,

The shaft that nestled there she hath removed,

And that consuming grief for my dead child

Which poisoned all the life of me is dead.

[79] [132] To-day my heart is healed, my yearning stayed,vPerfected the deliverance wrought in me.[3]

Lo! I for refuge to the Buddha go —

The only wise — the Order and the Norm.[4]

Now, because those 500 Bhikkhums were versed in the teaching of Paṭācārā, therefore they got the name of The Paṭācārā's.

LI

Vasiṭṭhī[5]

She, too, faring under former Buddhas like the foregoing, was, in this Buddha-era, reborn in a clansman's family at Vesalī. Her parents gave her in marriage to a clansman's son of equal rank, and she, bearing one son, lived happily with her husband. But when the child was able to run about, he died; and she was worn and maddened with grief. And while the relatives were administering healing to the husband, she, unknown to them, ran away raving, and wandered round and round till she came to Mithilā. There she saw the Exalted One going down the next street, self-controlled, self-contained, master of his faculties. And at the sight of the wondrous Chief,[6] and through the potency of the Buddha, she regained her normal mind from the frenzy that had befallen her. Then the Master taught her the Norm in outline, and in agitation she asked him that she might enter the Order, and by his command she was admitted. Performing all requisite duties and preliminaries, she established insight, and, striving with might and main, and with ripening knowledge, she soon attained Arahantship, together with thorough [80] grasp of the Norm in form and in spirit. Reflecting on her attainment, she exulted thus:

[133] Now here, now there, lightheaded, crazed with grief,

Mourning my child, I wandered up and down,

Naked, unheeding, streaming hair unkempt,

[134] Lodging in scourings of the streets, and where

The dead lay still, and by the chariot-roads —

So three years long I fared, starving, athirst.

[135] And then at last I saw Him, as He went

Within that blessed city Mithilā:

Great Tamer of untamèd hearts, yea, Him,

The Very Buddha, Banisher of fear.

[136] Came back my heart to me, my errant mind

Forthwith to Him I went low worshipping,

And there, e'en at His feet I heard the Norm.

For of His great compassion on us all,

'Twas He who taught me, even GOTAMA.[7]

[137] I heeded all He said and left the world

And all its cares behind, and gave myself

To follow where He taught, and realize

Life in the Path to great good fortune bound.

[138] Now all my sorrows are hewn down, cast out,

Uprooted, brought to utter end,

In that I now can grasp and understand

The base on which my miseries were built.

LII

Khemā

Now she, when Padumuttara was Buddha, became a slave to others, dependent for her livelihood on others, at Haṇsavati. And one day, seeing the Elder, Sujāta, seeking alms, she gave him three sweet cakes, and at the same time took down her hair[8] and gave it to the Elder, saying: 'May I in the future become a disciple, great in wisdom, of a Buddha!' After many fortunate rebirths as Queen among both gods and men, for that she had wrought good karma to the uttermost, she became a human, when Vipassi[9] was Buddha. Renouncing the world, she became a learned preacher of the Norm. Reborn, when Kakusandha was Buddha, in a wealthy family, she made a great park for the Order, and delivered it over to the Order with the Buddha at their head. She did this again when Koṇāgamana was Buddha. When Kassapa was Buddha she became the eldest daughter of King Kiki,[10] named Samaṇī, lived a pious life, and gave a cell to the Order. Finally, in this Buddha-era, she was born in Magadha, at Sāgala[11] as one of the King's family, and named Khema. Beautiful, and with skin like gold, she became the consort of King Bimbisara. While the Master was at the Bamboo Grove[12] she, being infatuated with her own beauty, would not go to see him, fearing he would look on this as a fault in her. The King bade persons praise the Grove to her to induce her to visit it. And accordingly she asked him to let her see it. The King went to the Vihāra, and seeing no Master, but determined that she should not get away, he instructed his men to let the [82] Queen see Him of the Ten Powers, even by constraining her. And this they did when the Queen was about to leave without meeting the Master. As they brought her reluctant, the Master, by mystic potency, conjured up a woman like a celestial nymph, who stood fanning him with a palmyra leaf. And Khema, seeing her, thought: 'Verily the Exalted One has around him women as lovely as goddesses. I am not fit even to wait upon such. I am undone by my base and mistaken notions!' Then, as she looked, that woman, through the steadfast will of the Master, passed from youth to middle age and old age, till, with broken teeth, grey hair, and wrinkled skin, she fell to earth with her palm-leaf. Then Khema, because of her ancient resolve, thought: 'Has such a body come to be a wreck like that? Then so will my body also!' And the Master, knowing her thoughts, said:

'They who are slaves to lust drift down the stream,

Like to a spider gliding down the web

He of himself has wrought. But the released,

Who all their bonds have snapt in twain,

With thoughts elsewhere intent, forsake the world,

And all delight in sense put far away.'[13]

The Commentaries say that when he had finished, she attained Arahantship, together with thorough grasp of the Norm in form and meaning. But according to the Apadāna, she was established only in the Fruit of one who has entered the Stream, and, the King consenting, entered the Order ere she became an Arahant.[14]

Thereafter she became known for her great insight, and was ranked foremost herein by the Exalted One, seated in the conclave of Ariyans at the Jeta Grove Vihāra.

And as she sat one day in siesta under a tree, Māra the Evil One, in youthful shape, drew near, tempting her with sensuous ideas:

[83] [139] Thou art fair, and life is young, beauteous Khema![15]

I am young, even I, too — Come, O fairest lady!

While in our ear fivefold harmonies murmur melodious,

Seek we our pleasure.'

[140] 'Through this body vile, foul seat of disease and corruption,

Loathing I feel, and oppression. Cravings of lust are uprooted.

[141] Lusts of the body and sense-mind[16] cut like daggers and javelins.

Speak not to me of delighting in aught of sensuous pleasure!

Verily all such vanities now no more may delight me.

[142] Slain on all sides is the love of the world, the flesh, and the devil.[17]

Rent asunder the gloom of ignorance once that beset me.

Know this, O Evil One! Destroyer, know thyself worsted!

[143] Lo! ye who blindly worship constellations of heaven,

Ye who fostering fire in cool grove, wait upon Agni,

Ignorant are ye all, ye foolish and young, of the Real,

Deeming ye thus might find purification from evil.[18]

[84] [144] Lo! as for me I worship th' Enlightened, the Uttermost Human,[19]

Utterly free from all sorrow, doer of Buddha's commandments.'

LIII

Sujātā

She, too, having made her resolve under former Buddhas, and accumulating good of age-enduring efficacy in this and that rebirth, and consolidating the essential conditions for emancipation, was, in this Buddha-era, reborn at Sāketa, in the Treasurer's family. Given by her parents in marriage to a Treasurer's son of equal rank, she lived happily with him. Going one day to take part in an Astral Festival[20] in the pleasure-grounds, she was returning with her attendants to the town, when, in the Añjana Grove, she saw the Master, and her heart being drawn to him, she drew near, did obeisance, and seated herself. The Master, finishing his discourse in order, and knowing the sound state of her mind, expounded the Norm to her in an inspiring lesson. Thereat, because her intelligence was fully ripe, she, even as she sat, attained Arahantship, together with thorough grasp of the Norm in form and meaning. Saluting the Master, and going home, she obtained her husband's and her parents' consent, and by command of the Master was admitted to the Order of Bhikkhunīs. Reflecting on her attainment, she exulted thus:

[85] [145] Adorned in finery, in raiment fair,

In garlands wreathed, powdered with sandalwood,

Bedecked with all my jewelry, begirt

[146] With troop of handmaidens, and well-supplied

With food solid and soft, and drink enow,

From home I drove me to the fair pleasaunce.

[147] There did we sport and make a merry time,

Then gat us once more on the homeward way.

So entered we the grove called Añjana,

Hard by Sāketa, where amidst the trees

Stands the Vihāra [of the holy men].

[148] Him saw I sitting there, Light of the World,

And went into his presence worshipping.

And of his great compassion for us all,

He taught to me the Norm — the One who Sees!

[149] Forthwith I, too, could pierce and penetrate,

Hearing the truth taught by the mighty Seer,

For there, e'en as I sat, my spirit touched[21]

The Norm Immaculate, th' Ambrosial Path.

[150] Then first it was I left the life of home,

When the blest Gospel[22] I had come to know,

And now the Threefold Wisdom have I won.

O wise and sure the bidding of the Lord!

LIV

Anopamā

She, too, having made resolve under former Buddhas, and heaping up good of age-enduring efficacy in this and that rebirth, perfecting the conditions tending to bring about emancipation, was, in this Buddha-era, reborn at Sāketa as the daughter of the Treasurer, Majjha. Because of her beauty she got the name 'Peerless' (An-opamā). When she grew up, many rich men's sons, Kings' ministers, and Princes, sent messengers to the father, saying: 'Give us your daughter Anopamā, and we will give this, or that.' Hearing of this, she — for that the promise of the highest was in her — thought: 'Profit to me in the life of the House there is none'; and sought the Master's presence. She heard him teach, and her intelligence maturing, the memory of that teaching, and the strenuous effort for insight she made, established her in the Third Path — that of No-return. Asking the Master for admission, she was by his order admitted among the Bhikkhunīs. And on the seventh day thereafter, she realized Arahantship. Reflecting thereon, she exulted:

[151] Daughter of Treas'rer Majjha's famous house,

Rich, beautiful and prosperous, I was born

To vast possessions and to lofty rank.

[152] Nor lacked I suitors — many came and wooed;

The sons of Kings and merchant princes came

With costly gifts, all eager for my hand.

And messengers were sent from many a land

With promise to my father: 'Give to me

[153] Anopamā, and look! whate'er she weighs,

Anopamā thy daughter, I will give

Eightfold that weight in gold and gems of price.'

[87] [154] But I had seen th' Enlightened, Chief o' the World,

The One Supreme. In lowliness I sat

And worshipped at his feet. He, Gotama,

[155] Out of his pity taught to me the Norm.

And seated even there I touched in heart

The Anagami-Fruit, Third of the Paths,

And knew this world should see me ne'er return.

[156] Then cutting off the glory of my hair,

I entered on the homeless ways of life.

'Tis now the seventh night since first all sense

Of craving drièd up within my heart.

LV

Mahā-Pajāpatī the Gotamid

Now she was born, when Padumuttara was Buddha, in the city of Haṇsavati, in a clansman's family. Hearing the Master preaching, and assigning the foremost place for experience to a certain Bhikkhunī, she vowed such a place should one day be hers. Then, after many births, once more was she reborn in the Buddha-empty era, between Kassapa and our Buddha, at Benares, as the forewoman among 500 slave-girls.[23] Now, when the rains drew near, five Silent Buddhas came down from the Nandamūlaka mountain-cave to Isipatana, seeking alms; and those women got their husbands to erect five huts for the Buddhas during the three rainy months, and they provided them with all they required during that time. Reborn once more in a [88] weaver's village near Benares, in the headman's family, she again ministered to Silent Buddhas. Finally, she was reborn, shortly before our Master came to us, at Devadaha, in the family of Maha-Suppabuddha.[24] Her family name was Gotama, and she was the younger sister of the Great Māyā. And the interpreters of birthmarks declared that the children of both sisters would be Wheel-rolling Rulers.[25] Now, King Suddhodana, when he came of age, held a festival, and wedded both the sisters. After this, when our Master had arisen, and, in turning the excellent wheel of the Norm, came in course of fostering souls to Vesalī, his father, who had reached Arahantship, died.

Then the great Pajāpatī, wishing to leave the world, asked the Master for admission, but obtained it not. Then she cut off her hair, put on the robes, and at the end of the sermon now forming the Suttanta on strife and contention, she sallied forth, and together with 500 Sakya ladies whose husbands had renounced the world, went to Vesalī, and asked the Master, through Ānanda the Thera, for ordination. This she then obtained, with the eight maxims for Bhikkhunīs.

Thus ordained, the Great Pajāpatī came and saluted the Master, and stood on one side. Then he taught her the Norm; and she, exercising herself and practising, soon after obtained Arahantship, accompanied by intuitive and analytical knowledge. The remaining 500 Bhikkhunīs, after Nandaka's homily, became endowed with the six branches of intuitive knowledge.

Now, one day, when the Master was seated in the conclave of Ariyans at the great Jeta Grove Vihāra, he assigned the foremost place in experience to Great Pajāpatī, the Gotamid. She, dwelling in the bliss of fruition and of Nibbāna, testified her gratitude one day by declaring her añña before the Master, in praising his virtue, who had brought help where before there had been none:

[89] [157] Buddha the Wake,[26] the Hero, hail! all hail!

Supreme o'er every being that hath life,

Who from all ill and sorrow hast released

Me and so many, many stricken folk.[27]

[158] Now have I understood how Ill doth come.

Craving, the Cause, in me is drièd up.

Have I not trod, have I not touched the End

Of Ill — the Ariyan, the Eightfold Path?

[159] Oh! but 'tis long I've wandered down all time.

Living as mother, father, brother, son,

And as grandparent in the ages past —

Not knowing how and what things really are,

And never finding what I needed sore.

[160] But now mine eyes have seen th' Exalted One;

And now I know this living frame's the last,

And shattered is th' unending round of births.

No more Pajāpatī shall come to be!

[161] Behold the company who learn of him —

In happy concord of fraternity,

Of strenuous energy and resolute,

From strength to strength advancing toward the Goal —

The noblest homage this to Buddhas paid.[28]

[162] Oh! surely for the good of countless lives

Did sister Māyā bring forth Gotama,

Dispeller of the burden of our ill,

Who lay o'erweighted with disease and death!

LVI

Guttā

She, too, having made her resolve under former Buddhas, and accumulating good of age-enduring efficacy in this and that rebirth, and consolidating the essential conditions for emancipation, was, in this Buddha-era, reborn at Sāvatthī, in a brahmin's family, and named Guttā. When adolescent, life in the house became repugnant to her, and she obtained her parents' consent to enter the Order under the Great Pajāpatī. Thereafter, though she practised with devotion, her heart long persisted in running after external interests, and this destroyed concentration. Then the Master, to encourage her, sent forth glory, and appeared near her, as if seated in the air, saying these words:

[163] Bethink thee, Guttā, of that high reward[29]

For which thou wast content to lose thy world,

Renouncing hope of children, lure of wealth.

To that direct and consecrate the mind,

Nor give thyself to sway of truant thoughts.

[164] Deceivers ever are the thoughts of men,

Fain for the haunts where Māra finds his prey;

And running ever on from birth to birth,

To the dread circle bound — a witless world.

[165] But thou, O Sister, bound to other goals,

Thine is't to break those Fetters five: the lust

Of sense, ill-will, delusion of the Self,

The taint of rites and ritual, and doubt,

[166] That drag thee backward to the hither shore.

'Tis not for thee to come again to this!

[91] [167] Get thee away from life-lust,[30] from conceit,

From ignorance, and from distraction's craze;

Sunder the bonds; so only shalt thou come

To utter end of Ill. Throw off the Chain

[168] Of birth and death — thou knowest what they mean.

So, free from craving, in this life on earth,

Thou shalt go on thy way calm and serene.

And when the Master had made an end of that utterance, the Sister attained Arahantship, together with thorough grasp of the Norm in form and meaning. And exulting thereon, she uttered those lines in their order as spoken by the Exalted One, whence they came to be called the Therī's psalm.

LVII

Vijayā

She, too, having made her resolve under former Buddhas, and heaping up good of age-enduring efficacy, was, in this Buddha-era, reborn at Rājagaha, in a certain clansman's family. When grown up she became the companion of Khemā, afterwards Therī, but then of the laity. Hearing that Khemā, had renounced the world, she said: 'If she, as a King's consort, can leave the world, surely I can.' So to Khemā, Therī she went, and the latter, discerning whereon her heart was set, taught her the Norm so as to agitate her mind concerning rebirth, and to make her seek comfort in the system. And so it came to pass; and the Therī ordained her. She, serving as was due, and studying as was due, [92] grew in insight, and, the promise being in her, soon attained to Arahantship, together with thorough grasp of the Norm in form and meaning. And she, reflecting thereon, exulted thus:

[169] Four[31] times, nay five, I sallied from my cell,

And roamed afield to find the peace of mind

I lacked, and governance of thoughts

I could not bring into captivity.

[170] Then to a Bhikkhunī[32] I came and asked

Full many a question of my doubts.

To me she taught the Norm: the elements,

[171] Organ and object in the life of sense,[33]

[And then the factors of the Nobler life:]

The Ariyan Truths, the Faculties, the Powers,

The Seven Features of Awakening,

The Eightfold Way, leading to utmost good.

[172] I heard her words, her bidding I obeyed.

While[34] passed the first watch of the night there rose

Long memories of the bygone line of lives.

[173] While passed the second watch, the Heavenly Eye,

Purview celestial, I clarified.

While passed the last watch of the night, I burst

And rent aside the gloom of ignorance.

[93] [174] Then, letting joy and blissful ease of mind

Suffuse my body, seven days I sat,

Ere stretching out cramped limbs I rose again.

Was it not rent indeed, that muffling mist?[35]

Euhemerize. After Euhemerus, 4th Cent. BC Greek mythologist who maintained that the stories of the Gods were really the stories of mortals. So: to suggest that a myth is the story of some ordinary human event made grand over time. It is interesting to note that it was in fact a practice to 'immortalize' the Ceasers and other great figures.

![]() — p.p.

— p.p.

[1] Pañcasatā Paṭācārā. Dr. Neumann, who disregards the Commentary throughout as a mere exegesis and of less than no historical value, renders Pañcasatā by 'of fivefold subtlety' — die fünfmal Feine — sata being taken as 'one who has sati' (memory, mindfulness, discernment), Sanskrit smṛta. I believe the expression pañcasata occurs nowhere else; nor is there anything in the gāthā's to justify the soubriquet. Nor am I concerned to euhemerize the, to us, mythical absurdity of 500 bereaved mothers all finding their way to one woman, illustrious teacher and herself bereaved mother though she might be. Five hundred, and one or two more such 'round numbers,' are, in Pali, tantamount simply to our 'dozens of them,' 'an hundredfold,' and the like. But, besides this, the phenomena of huge cities and swarming population are not, in countries of ancient civilization, matters of yesterday's growth, as in our case.

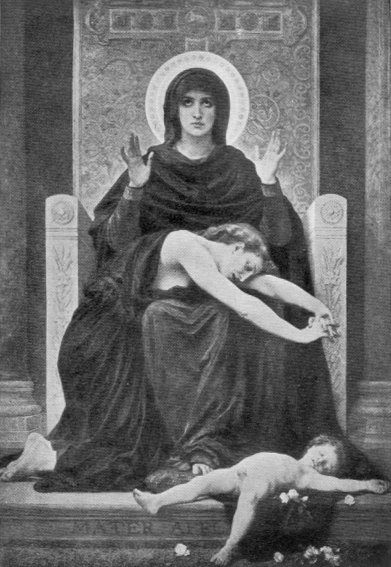

Bouguereau's 'Vierge Consolatrice'

'Lo! ask thyself again whence came thy son

To bide on earth this little breathing-space?'

[2] The sharp contrast between this chant of consolation and that which any other religious anthology affords is sufficiently interesting. But if the burden of the chant, in its varied iteration, be imagined, not tripped off on the tongue of a cheerful critic or a disapproving other-believer, but uttered in grave, tender accents, coming from a heart that felt intensely because it had so ached, and from a mind that understood and was therefore serene ... Even so might Bouguereau's 'Vierge Consolatrice' speak, her great wise eyes looking forth over the anguished bereaved sister flung on her lap, while the dead child lies below at her feet.

[3] Parinibbuttā, Cf. ver. 53.

[4] Cf. p. 40, n 3.

[6] Nāga, a term not seldom applied to a great and mysterious personality. I can find no English equivalent.

[7] More than once in these verses — never, I believe, in prose — the family name of the Buddha is used by the faithful — e.g., Ps. liv.

[8] The usual word 'cut off' is not used.

[9] First of the seven Buddhas of the Pitakas. See Dialogues of the Buddha, i. 3.

[11] Cf. Ps. xxxvii.

[12] Presented by Bimbisara to the Order, six miles from Rājagaha. For a more detailed version of this story (I have slightly condensed a slightly less detailed original), see Mrs. Bode, J.R.A.S., 1893, p. 529. ff.

[13] Dhammapada, ver. 347.

[14] The Apadāna version in ninety-two verse-couplets is then quoted. Arahantship outside the Order was very rare, though not unknown.

[15] In the text the usual √loka metre is employed.

[16] I.e., the Khandhas, or five constituents making up a person under conditions of sense experience.

[17] Nandi, sensuous delight, implying more or less love of all three.

[18] These two lines, which are somewhat turgidly amplified, run in literal terseness thus: 'Ye foolish young ones, who know not things as they really have come to be, [those rites] ye have fancied to be purification' (suddhi).

[19] Purisuttamo, 'supreme among men.'

[20] Nakkhattakīlaṇ, constellation-sports. Cf. verse 143 in the preceding Psalm.

[21] This is another subtle stroke of artistry, to let the visual emphasis in the poem culminate in the intenser metaphor of touch. 'Seeing is believing, but touch is the real thing.' The word is frequently so used in the Pitakas, but without the theosophical mysticism of the Neoplatonic άφή.

[22] Saddhamma means good teaching (εύαγγέλιον), not, of course, God's 'spell.'

[23] See this episode in fuller detail in Mrs. Bode, op. cit., p. 523 ff. The two Commentaries agree in all salient points, ours being less detailed. The above is considerably condensed. The Apadāna devotes 190 verse-couplets to the chronicle of this 'Great' Mother of the Sisters' Order.

[24] In the Apadāna he is called Añjana the Sākiyan.

[25] I.e., should be Emperors, either of worldly dominions or else of the hearts of men.

[26] Buddho = awake.

[27] So K.E. Neumann: Erlöser vielem vielem Volk.

[28] Esā Buddhāna-vandanā. Cf. Savonarola's words: '... righteousness of living, which is the grandest homage and truest worship that the creature can render to his Creator' (The Triumph of the Cross).

[29] Attho, good, advantage, profit.

[30] Longing to live again, embodied or disembodied. This and the following three terms are the last five Fetters, 'the sundering of which leads immediately to Arahantship.' See Rhys Davids, American Lectures, 141-152.

[31] = Ps. xxviii and xxx.

[32] Here is a case where Atthakathā and Gāthā are badly welded, as he who runs may read. The commentator, nothing doubting, identifies the Bhikkhunī as Khemā.

[33] Cf. Ps. xxx., xxxviii. The following 'factors' give twenty-five of the thirty-seven known as the Bodhipakkhiyā Dhammā, omitting the four applications of mindfulness (satipaṭṭhānā), the four stages of potency (iddhipādā), and the four right efforts (sammāppadhānāni), but introducing the doctrinal four truths.

[34] = Ps. xlviii.

[35] This question sign is a translator's liberty. The Pali reiterates only the final stage of relief and attainment.