RHYS DAVIDS: BUDDHIST INDIA

Chapter VI

Economic Conditions

THERE has been as yet no attempt to reconstruct a picture of the economic conditions at any period in the early history of India. Professor Zimmer, Dr. Fick, and Professor Hopkins have dealt incidentally with some of the points on the basis respectively of the Vedas, the Jātakas, and the Epics. But generally speaking the books on India have been so exclusively concerned with questions of religion and philosphy, of literature and language, that we seem apt to forget that the very necessities of life, here as elsewhere, must have led the people to occupy their time very much, not to say mostly, with other matters than those, with the earning of their daily bread, with the accumulation and distribution of wealth. The following remarks will be chiefly based on Mrs. Rhys-Davids's articles on this important subject in the Economic Journal, for 1901, and in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, for 1901. And numbers given in this chapter as references, without letters referring to other sources, refer to the pages of the latter article.

[88] When the King of Magadhā, the famous (and infamous) Ajātasattu, made his only call upon the Buddha, he is said[1] to have put a puzzle to the teacher to test him — a puzzle characteristic of the King's state of mind. It is this:

"What in the world is the good of your renunciation, of joining an Order like yours? Other people (and here he gives a list), by following ordinary crafts, get something out of them. They can make themselves comfortable in this world, and keep their families in comfort. Can you, Sir, declare to me any such immediate fruit, visible in this world, of the life of a recluse?"

The list referred to is suggestive. In the view of the King the best examples of such crafts were the following:

| 1. Elephant-riders | 17. Bath-attendants. |

| 2. Cavalry. | 18. Confectioners. |

| 3. Charioteers. | 19. Garland-makers. |

| 4. Archers. | 20. Washermen. |

| 5–13. Nine different grades of army folk. |

21. Weavers. 22. Basket-makers. |

| 14. Slaves. | 23. Potters. |

| 15. Cooks. | 24. Clerks. |

| 16. Barbers. | 25. Accountants. |

These are just the sort of people employed about a camp or a palace. King-like, the King considers chiefly those who minister to a king, and are dependent upon him. In the answer he is most politely reminded of the peasant, of the tax-payer, on whom both he and his depended. And it is evident enough

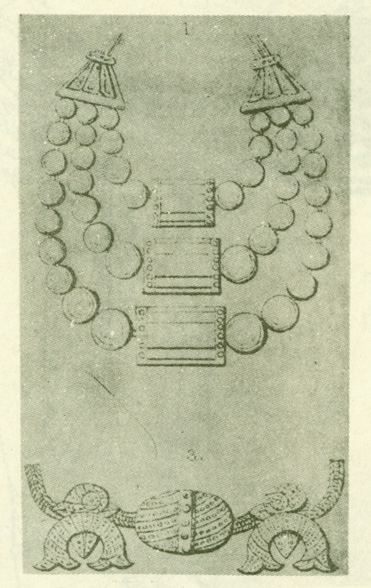

![Specimens of ancient jewelry found in the Sakiya tope. Fig. 17 Specimens of ancient jewelry found in the Sakiya tope. [From J.R.A.S., 1898.]](../../resources/dhammatalk/rd_buddhist_india/bi_fig.017.jpg)

Fig. 17 Specimens of ancient jewelry found in the Sākiya tope. [From J.R.A.S., 1898.]

[90] from other passages that the King's list is far from exhaustive. There is mention, in other documents of the same age, of guilds of work-people; and the number of these guilds is often given afterwards as eighteen. Four of these are mentioned by name.[2] But a list of the whole eighteen has unfortunately not yet been found. It would probably have included the following:

1. The workers in wood. They were not only carpenters and cabinet-makers, but also wheel-wrights; and the builders of houses, and of ships, and of vehicles of all sorts (863).

2. The workers in metal. They made any iron implements — weapons of all kinds, ploughshares, axes, hoes, saws, and knives. But they also did finer work — made needles, for instance, of great lightness and sharpness, or gold and (less often) silver work of great delicacy and beauty (864).

3. The workers in stone. They made flights of steps, leading up into a house or down into a reservoir; faced the reservoir; laid foundations for the woodwork of which the upper part of the houses was built; carved pillars and bas-reliefs; and even did finer work such as making a crystal bowl, or a stone coffer (864). Beautiful examples of these two last were found in the Sākiya Tope.

4. The weavers. They not only made the cloths which the people wrapped round themselves as dress, but manufactured fine muslin for export, and worked costly and dainty fabrics of silk cloth and fur into rugs, blankets, coverlets, and carpets.[3]

![Old indian girdle of jewels. Fig. 18 Old indian girdle of jewels. [From the figure of Sirima Devata on the Bharahat Tope. Pl. li.]](../../resources/dhammatalk/rd_buddhist_india/bi_fig.018.jpg)

Fig. 18 Old indian girdle of jewels. [From the figure of Sirīma Devata on the Bharahat Tope. Pl. li.]

[92] 5. Leather workers, who made the numerous sorts of foot-covering and sandals worn by the people mostly in cold weather; and also the embroidered

Fig. 19 Old indian necklaces.

and costly articles of the same kind mentioned in the books (865).

6. Potters, who made all sorts of dishes and bowls for domestic use; and often hawked their goods about for sale.

[93] 7. Ivory workers, who made a number of small articles in ivory for ordinary use, and also costly carvings and ornaments such as those for which India is still famous (864).

8. Dyers, who coloured the clothes made by the weavers (864).

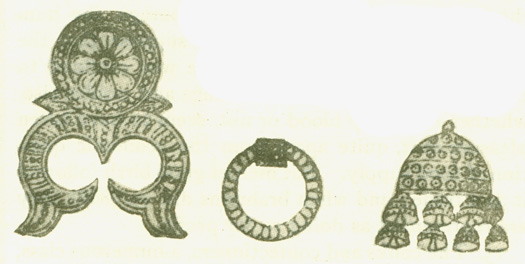

9. Jewellers, some of whose handiwork has survived, and is also so often represented in bas-reliefs that we know fairly well the shape and size of the ornaments they made.

Fig. 20 Old indian locket [1-3/4" h.]. Old indian earring [3/4" h.]. Old indian locket [7/8" h.].

10. The fisher folk. They fished only in the rivers. There is no mention of sea-fishing known to me.

11. The butchers, whose shops and slaughterhouses are several times mentioned (873).

12. Hunters and trappers, mentioned in various passages as bringing the animal and vegetable products of the woods, and also venison and game, for sale on carts into the city (873). It is doubtful whether they were formed into guilds. But their industry was certainly a very important one. The [94] large stretches of forest, open to all, separating most of the settlements; the absence of any custom of breeding cattle for the meat-market; the large demand for ivory, fur, sinews, creepers, and all the other produce of the woods; and the congeniality of the occupation, all tended to encourage the hunters. And there is no reason to suppose that the very ancient instinct of the chase was confined to the so-called savages. The kings and nobles also, whether Aryan by blood or not, seem to have taken pleasure in it, quite apart from the economic question of food supply. But men of good birth followed it as a trade; and when brahmins did so (868) they are represented as doing so for profit.

13. The cooks and confectioners, a numerous class, probably formed a guild. But there is no passage saying that they did.

14. The barbers and shampooers had their guilds. They dealt in perfumes, and were especially skilled in arranging the elaborate turbans worn by the wealthier classes. (Figs. 21, 22.)

15. The garland-makers and flower-sellers (866).

16. Sailors, occupied for the most part in the traffic up and down the great rivers, but also going to sea. In some of our earliest documents[4] we hear of sea voyages out of sight of land; and in the later documents, such as the Jātakas, the mention of such voyages is frequent (872). So the earlier documents speak of voyages lasting six months made in ships (nāvā, perhaps, "boats") which could be drawn up on

Fig. 21 Medallion on the Bharahut tope. Pl. xxiv. Fig. 3.]

[96] shore in the winter,[5] And later texts, of about the third century B.C., speak of voyages down the Ganges from Benares to the mouth of the river and thence across the Indian Ocean to the opposite coast of Burma; and even from Bharukaccha (the modern Baroch) round Cape Comorin to the same destination (871). It is clear, therefore, that during the whole of this period the occupation of sailor was neither unfrequent nor unimportant.

17. The rush-workers and basket-makers (868).

18. Painters (865). They were mostly house-painters. The woodwork of the houses was often covered with fine chunam plaster and decorated with painting. But they also painted frescoes.[6] These passages tell us of pleasure-houses, adorned with painted figures and patterns, belonging to the kings of Magadhā and Kosalā; and such frescoes were no doubt similar in character to, but of course in an earlier style than, the well-known ancient frescoes of the seventh and eighth centuries a.d. on the Ajanta Caves, and of the fifth century on the Sīgiri Rock in Ceylon.

It is doubtful with regard to two or three in this list whether they were organised in guilds (seniyo, pūgā). But it is certain that these were among the most important branches of handicraft apart from agriculture; and most of them had, no doubt, their guilds not unlike the mediæval guilds in Europe. It is through their guilds that the king summons the people on important occasions (865). The Aldermen [97] or Presidents (jeṭṭhaka or pamukhā) of such guilds are sometimes described as quite important persons, wealthy, favourites at the court. The guilds are said to have had powers of arbitration between the mem-

Fig. 22 Ancient Indian Head-Dress. [From a medallion on the Bharahat Tope. Pl. xxiv. Fig. 2.]

bers of the guild and their wives. And disputes between one guild and another were in the jurisdiction of the mahā-seṭṭhi, the Lord High Treasurer, who acted as a sort of chief Alderman over the Aldermen of the guilds (865).

Octroi duties. > Authorize. An authorization. In other contexts a grant made by a king which amounted to a limitation of his authority. So, often, a grant made to some person to collect and keep the taxes due from a town or city. Here: Taxes on commodities brought into a town or city or district.

![]() — p.p.

— p.p.

[98] Besides the peasantry and the handicraftsmen there were merchants who conveyed their goods either up and down the great rivers, or along the coasts in boats; or right across country in carts travelling in caravans. These caravans, long lines of small two-wheeled carts, each drawn by two bullocks, were a distinctive feature of the times.[7] There were no made roads and no bridges. The carts struggled along, slowly, through the forests, along the tracks from village to village kept open by the peasants. The pace never exceeded two miles an hour. Smaller streams were crossed by gullies leading down to fords, the larger ones by cart ferries. There were taxes and octroi duties at each different country entered (875); and a heavy item in the cost was the hire of volunteer police who let themselves out in bands to protect caravans against robbers on the way (866). The cost of such carriage must have been great; so great that only the more costly goods could bear it.

The enormous traffic of today in the carriage of passengers, food-stuffs, and fuel was non-existent. Silks, muslins, the finer sorts of cloth and cutlery and armour, brocades, embroideries and rugs, perfumes and drugs, ivory and ivory work, jewelry and

Fig. 23 Anāthapiṇḍika's gift of the Jetavana park. [From the Bharahat Tope, Pl. lxvii.]

[100] gold (seldom silver), — these were the main articles in which the merchant dealt.

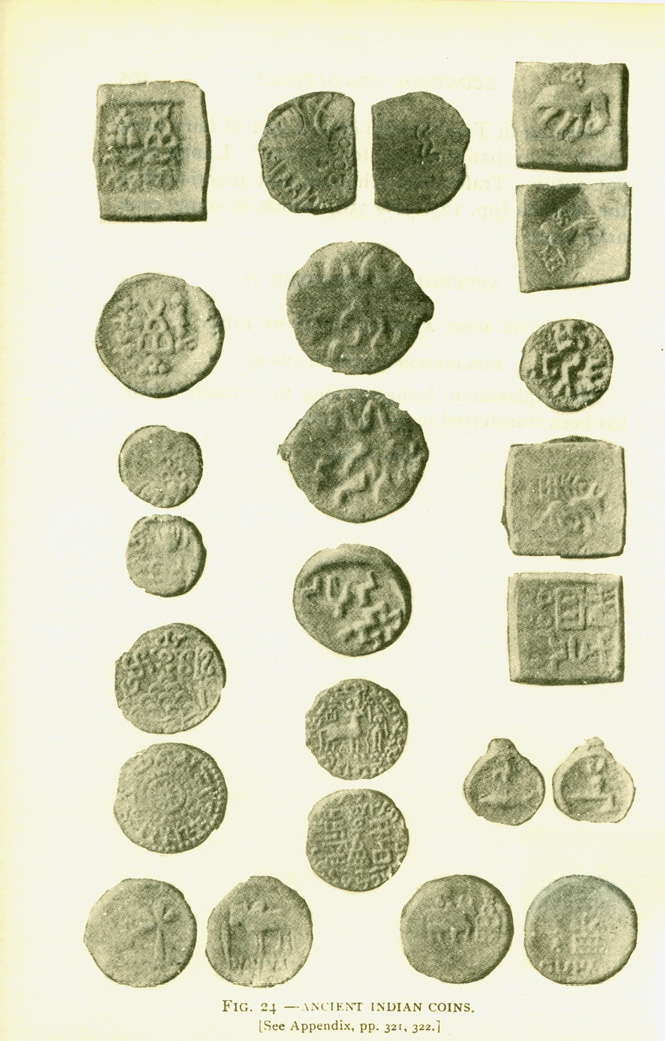

The older system of traffic by barter had entirely passed away never to return. The later system of a currency of standard and token coins issued and regulated by government authority had not yet arisen. Transactions were carried on, values estimated, and bargains struck in terms of the kahāpaṇa, a square copper coin weighing about 146 grains, and guaranteed as to weight and fineness by punch-marks made by private individuals.[8] Whether these punch-marks are the tokens of merchants, or of guilds, or simply of the bullion dealer, is not certain (874). (Fig. 24.)

No silver coins were used (877). There were half and quarter kahāpaṇas, and probably no other sort. The references to gold coins are late and doubtful; and no such coins have been found. Some thin gold films with punch marks on them were found in the Sākiya Tope, but these are too flimsy to have been used in circulation as coins (878). It is interesting to notice that Alexander, when in India, struck a half kahāpaṇa copper piece, square (in imitation of the Indian money), and not round like the Greek coins of the time.

It is only in later times that we hear (as for instance in Manu, 8. 401) of any market price being fixed by government regulation. In the sixth century B.C. there is only an official called the Valuer, whose duty it was to settle the prices of goods [101] ordered for the palace — which is a very different thing (875). And there are many instances, incidentally given, of the prices of commodities fixed, at different times and places, by the haggling of the market (875). These are all collected together in the article referred to (at pp. 882, foll.); and the general result seems to be that though the kahāpaṇa would be worth, at the present value of copper, only five sixths of a penny, its purchasing power then was about equivalent to the purchasing power of a shilling now.

Besides the coins, there was a very considerable use of instruments of credit. The great merchants in the few large towns gave letters of credit on one another. And there is constant reference to promissory notes (879). The rates of interest are unfortunately never stated. But interest itself is mentioned very early; and the law books give the rate of interest current at a somewhat later date for loans on personal security as about eighteen per cent. per annum (881).

There were no banking facilities. Money was hoarded either in the house, or buried in jars in the ground, or deposited with a friend, a written record of the transaction being kept (881).

The details of prices above referred to enable us to draw some conclusion as to the spending power of the poor, of the man of the middle classes, and of the wealthy merchants and nobles respectively. Of want, as known in our great cities, there is no evidence. It is put down as the direst misfortune known that a free man had to work for hire. And [102] there was plenty of land to be had for the trouble of clearing it, not far from the settled districts.

On the other hand, the number of those who could be considered wealthy from the standards of those times (and of course still more so from our own) was very limited. We hear of about a score of monarchs, whose wealth consisted mainly of the land tax, supplemented by other dues and perquisites; of a considerable number of wealthy nobles, and some priests, to whom grants had been made of the tithe arising out of certain parishes or counties[9] or who had inherited similar rights from their forefathers; of about a dozen millionaire merchants in Takkāsilā, Sāvatthi, Benares, Rājagaha, Vesāli, Kosambī, and the seaports (882), and of a considerable number of lesser merchants and middlemen, all in the few towns. But these were the exceptions. There were no landlords. And the great mass of the people were well-to-do peasantry, or handicrafts-men, mostly with land of their own, both classes ruled over by local headmen of their own selection.

Before closing this summary of the most important economic conditions in Northern India in the sixth century B.C. it may be well to bring together the few notices we have in the books about the trade routes. There is nothing about them in the pre-Buddhistic literature. In the oldest Pāli books we have accounts of the journeys of the wandering teachers; and as, especially for longer journeys, they will generally have followed already established routes, this is incidental evidence of such as were then in [103] use by traders. Later on, we have accounts of routes actually followed by merchants, either on boats, or with their caravans of bullock carts. We can thus draw up provisionally the following list:

1. North to South-west. Sāvatthi to Patiṭṭhāna (Paithan) and back. The principal stopping places are given[10] (beginning from the south) as Māhissati, Ujjeni, Gonaddha, Vedisa, Kosambī, and Sāketa.

2. North to South-east. Sāvatthi to Rājagaha. It is curious that the route between these two ancient cities is never, so far as I know, direct, but always along the foot of the mountains to a point north of Vesāli, and only then turning south to the Ganges. By taking this circuitous road the rivers were crossed at places close to the hills where the fords were more easy to pass. But political considerations may also have had their weight in the original choice of this route, still followed when they were no longer of much weight.[11] The stopping places were (beginning at Sāvatthi), Setavya, Kapilavastu, Kusinārā, Pāvā, Hatthi-gāma, Bhaṇḍagama, Vesāli, Pātaliputta, and Nālandā. The road probably went on to Gaya, and there met another route from the coast, possibly at Tāmralipti, to Benares.[12]

3. East to West. The main route was along the great rivers, along which boats plied for hire. We even hear of express boats. Upwards the rivers were used along the Ganges as far west as Sahajāti,[13] and along the Jumna as far west as Kosambī.[14] Downwards, in later times at least, the boats went [104] right down to the mouths of the Ganges, and thence either across or along the coast to Burma.[15] In the early books we hear only of the traffic downward as far as Magadhā, that is, to take the farthest point, Champā. Upwards it went thence to Kosambī, where it met the traffic from the south (Route 1), and was continued by cart to the south-west and north-west.

Besides the above we are told of traders going from Videha to Gandhārā,[16] from Magadhā to Sovīra,[17] from Bharukaccha round the coast to Burma,[18] from Benares down the river to its mouth and thence on to Burma,[19] from Champā to the same destination.[20] In crossing the desert west of Rājputana the caravans are said[21] to travel only in the night, and to be guided by a "land-pilot," who, just as one does on the ocean, kept the right route by observing the stars. The whole description of this journey is too vividly accurate to life to be an invention. So we may accept it as evidence not only that there was a trade route over the desert, but also that pilots, guiding ships or caravans by the stars only, were well known.

In the solitary instance of a trading journey to Babylon (Baveru) we are told that it was by sea, but the port of departure is not mentioned.[22] There is one story, the world-wide story of the Sirens, who [105] are located in Tambapaṇṇi-dīpa, a sort of fairy land, which is probably meant for Ceylon.[23] Lankā does not occur. Traffic with China is first mentioned in the Milinda (pp. 127, 327, 359), which is some centuries later.

APPENDIX TO CHAPTER VI

THE MOST ANCIENT COINS OF INDIA

EXPLANATION OF FIGS. 24 AND 25.

This explanation, being too long to be inserted here, has been transferred to pp. 321, 322.

Fig. 24 Ancient Indian coins. [See Appendix, pp. 321, 322.]

[1] D. 1. 51.

[2] At Jāt. 6. 427.

[3] D. 1. 7.

[4] Digha, 1. 222 (translated in Dialogues of the Buddha, 1. 283), Anguttara, 3. 368.

[5] Saṅyutta, 3. p. 155, 5. 51; Anguttara, 4. 127.

[6] Vin. ii. 151; iv. 47, 61, 298; Sum. 42, 84.

[7] The accompanying plate (Fig. 23) shows, in four scenes on the same bas-relief, Anatha Piṇḍika's famous gift of the Jetavana Park to the Order. To the left is the park, the ground of which is being covered with Kahapaṇas. In front is the bullock cart which has brought them. In the centre the donor holds in his hand the water of donation, the pouring out of which is to complete the legality of the gift. To the right are the huts to be afterwards put up in the park for the use of the Wanderers.

[8] See Figs. 1, 3, and 8 in the plate annexed to this chapter for examples of these oldest Kahapa?as.

[9] D. 1. 88; M. 2. 163, 3. 133; S. 82.

[10] In S. N. 1011–1013.

[11] Sutta Nipāta loc. cit., and Digha, 2.

[12] Vinaya Texts, 1. 81.

[13] Ibid. 3. 401.

[14] Ibid. 3. 382.

[15] That is at Thaton, then called Suvanna-bhumi, the Gold Coast. See Dr. Mabel Bode in the Sasana Vamsa, p. 12.

[16] Jāt. 3. 365.

[17] V. V. A. 370.

[18] Jāt. 3. 188.

[19] Ibid. 4. 15–17.

[20] Ibid. 6. 32–35.

[21] Ibid. 1. 108.

[22] Ibid., 3. 126. Has the foreign country called Seruma (Jāt. 3. 189) any connection with Sumer or the land of Akkad?

[23] Jāt. 2. 127.

Next: Chapter VII: Writing — The Beginnings

Previous: Chapter V: In the Town

[Preface] [Table of Contents][1. The Kings] [2. The Clans and Nations] [3. The Village] [4. Social Grades] [5. In the Town] [6. Economic Conditions] [7. Writing — The Beginnings] [8. Writing — It's Development] [9. Language and Literature. I. General View] [10. Literature. II. The Pāḷi Books] [11. The Jataka Book] [12. Religion — Animism] [13. The Brahmin Position] [14. Chandragupta] [15. Asoka] [16. Kanishka] [Appendix] [Index]

[Home] [Sutta Indexes] [Glossology] [Site Sub-Sections]