Sacred Books of the Buddhists

Volume III

Dīgha Nikāya

Dialogues of the Buddha

Part II

Sutta 19

Mahā-Govinda Suttantaṃ

The Lord High Steward

Translated from the Pāli by T.W. Rhys Davids

Public Domain

Originally published under the patronage of

His Majesty King Chulālankarana,

King of Siam

by The Pāli Text Society, Oxford

Introduction To The Mahā-Govinda Suttanta

THIS Suttanta is certainly, in some respects, among the most interesting in the collection; and for the history of the literature is of great importance.

The subject is twofold, both necessary points at the time, and both scarcely intelligible, without a little attention, to modern Western minds. Even in the East, and to Buddhists, the story now seems somewhat strange and antiquated. The success of the method of argument here adopted has been so far complete that the need of the argument has ceased, the point of view has changed, and the Suttanta, among the most popular in early times, is now, compared to others dealing with the positive side of the doctrine, considered of minor value.

The two points are those of the brahmins and the gods. The method of the argument is not to argue about anything; to accept the opponents' position throughout, and simply to out-flank it by making the gods and the brahmins themselves act and speak as quite good Buddhists, and take for granted the Buddhist position on ethical matters. This is of course, from one point of view, logically absurd. No militant brahmin, in favour of the pecuniary or social advantages allowed to brahmins by birth, would speak or act thus. No god, as he was supposed by his worshippers to be (and he existed only as such), would speak or act thus. But the composer (or composers) of the Govinda knew this quite well. And he is (or they are) scrupulously polite. The actions imputed to the brahmin and the gods, the words put into their mouths, are quite admirable. No one can blame the story-teller that they happen also to be Buddhist. The question as to what the good brahmin ought to be, what a good god ought to do or say, is quietly begged in the most delicate way. On this point — the ethical doctrine — the narrator is thoroughly in earnest; and he no less thoroughly enjoys the irony of the incongruities involved. It is the fashion to label all Buddhist writings, without discrimination, as insufferably dull; and the fashion [254] will be kept up, no doubt, among those who do not see the point of the really very able way in which, sometimes, it is all done. But we may be permitted to appreciate a clever story (even with a moral) in spite of the fact that the story part is a story — all make-believe, none of it historically true.

It has been pointed out above (Vol. I, 208), how a brahmin law book, at a time when the increasing respect paid to Wanderers and Bhikkhus threatened loss of prestige and profit to the sacrificing priests, puts into the mouth of Prajāpati the ferocious remark that he who praises such people (the wandering teachers, etc.) 'becomes dust and perishes.' The writer hoped (quite in vain as it turned out) to gain acceptance for his view by attributing it to a deity. This polemical device was quite in accord with the literary ethics of the day. The choice of the god has an artistic touch, and the anecdote se non è vero è ben trovato. Quite a number of other instances might be quoted from Indian books of all ages, though not from Pāli works later than the Nikāyas, nor from works written in Ceylon or Burma. And they are found also in other lands and other literatures. The device is peculiar, not to India, but to a certain stage in religious beliefs and literary taste. It is not in reality so good a device as, at first sight, it seems to be. There are many instances, like the one just quoted, where it has altogether failed. As applied here, in the Govinda, the device has failed as regards the brahmins.[i1] Where it has had a measure of success (that is, where the opinion thus fathered on a deity has become more or less an accepted opinion), it probably owes more to its validity, or to its appeal to the feeling of the times, than to the help of the deity invoked. The reader may be reminded that the habit of assuming that the deity is on one's own side, of taking it for granted that He shares one's own opinions, comes out quite clearly in modes of expression in constant use, even by very exalted personages, in the Europe of to-day.

Our Suttanta introduces us, in the first scene of the play, to heaven. There the gods rejoice at the increase in their numbers through the appearance, in their midst, of new gods produced by the good Karma of the followers of the new view of life put forward by Gotama. The king of the gods voices their satisfaction in a hymn; and then utters, in eight paragraphs, a eulogy on the Buddha. In scene two the still higher god, Mahā-Brahmā, appears. He desires to hear the eulogy, which is accordingly repeated for his benefit. He approves of it, and [255] adds that the Exalted One had long been as wise as that. In support of this he then tells the story which forms the second act, as it were, in many scenes. Here we have Brahmā's view (that is, the view of the author or authors of the Govinda) concerning the ideal brahmin. It is really very funny; whether we compare it with the actual brahmin of to-day, or with the brahmin as described in the epics and the law books, or with the brahmin as he probably really was in the Buddha's time. The last must have been in the authors' mind all the time; and the incongruity, though quite courteous, is sufficiently startling.

The episode told in Act I, Scenes 1 and 2, has already occurred, nearly word for word, in the Jana-Vasabha: -

Jana-Vasabha 12, 13 = Govinda 2, 3.

Jana-Vasabha 14-19 = Govinda 14-18.

The intervening passage (Govinda 4-13) contains Sakka's eulogy. A eulogy is also part of the Jana-Vasabha (§§ 22 ff.). But it is there put, at a later stage in the episode, into the mouth of Brahma, and deals accordingly with much deeper matters.[i2]

What is the conclusion to be drawn from these facts? They would be explained if the episode had existed in the community before either of these Suttantas had been put into its present shape; and had been so popular that it had been worked up, by different authors, in slightly differing ways. Or the author or authors of either Suttanta might have altered an episode, already incorporated in the other, to harmonize better with the particular lines of his own story. In that case it must be the Govinda version that is the later. In it the eulogy is put into the mouth of Sakka, and altered to suit that divinity, because Brahmā's speech was wanted for the story to follow. In either case it is evident that, at the time when these Suttantas were put together as we have them, the legendary material current among the community was still in a fluid, unstable, condition, so that it was not only possible, it was considered quite the proper thing, to add to or alter it.[i3] [256] The whole story is retold, in a Sanskrit dialect and in different phraseology and order, in the Mahāvastu, The following table will make the degree of the resemblance and difference plain.

| Mahā-Govinda Suttanta | Govindīya Sutta in Mahāvastu |

| § I | Vol. Ill, p. 197 |

| 2 | 198 |

| 4 | 199 |

| 5,6 | 200 |

| 8 | 201 |

| 9 | 200 |

| 10 | 201 |

| 12 | 201 |

| 13 | 198 |

| 17 | 203 |

| 19-27 | 202 |

| 29 | 204 |

| 30 | 205 |

| 31,32 | 206 |

| 34 | 207 |

| 35,36 | 208 |

| 37,38 | 209 |

| 43,44 | 210,211 |

| 45 | 212 |

| 46 | 213,214 |

| 47 | 215 |

| 48 | 217 |

| 49 | 218 |

| 50 | 216 |

| 51 | 210 |

| 56 | 220 |

| 57,58 | 222 |

| 60 | 223 |

| 61 | 215 |

Now we do not know exactly when and where Buddhists began to write in Sanskrit, though it was probably in Kashmir some time before the beginning of our era. They did not then translate into Sanskrit any Pāli book. They wrote new books. And the reason for this was twofold. In the first place they had already come to believe things very different from those contained in the canon; they were no longer in full sympathy with it. In the second place, though Pāli was never the vernacular of Kashmir, it was widely known there, and even very probably still used for literary work; translations were therefore not required.

This gives a possible explanation of the most astounding [257] fact we know about the Mahāvastu. It purports to be the Vinaya (that is, the Rules regulating the outward conduct of the members of the Order), as held by the school of the Lokottara-vadins. In M. Senart's admirable edition it fills three bulky volumes. There is not, from beginning to end of them, even one single Rule of the Order! No explanation has been given of this extraordinary state of things, though it was pointed out at once on the publication of the edition.[i4] Prof. Windisch in his able discussion (just above referred to) of the actual contents of the book does not refer to this remarkable omission.

The old Vinaya begins with the Sutta Vibhanga, that is, the Rules themselves elucidated by discussion of their origin and meaning. This occupies 615 pages in Oldenberg's editions. Then follow in 660 pages the Khandhakas, twenty-two in number, dealing with various points of Canon Law. At the beginning of these is an Introduction, explaining how the Order arose; and at the end an Appendix, on the Councils.[i5] This old Vinaya has never been translated into Sanskrit. The Mahāvastu is based on the Introduction to the Khandhakas, rewritten, added to, enormously expanded, and arranged according to the order of the Pāli Nidana Kathā. Now why did the Lokottara-vādins, in their Vinaya, omit practically the whole of the Vinaya, and confine themselves to rewriting the Introduction to what is only a part of the Vinaya? Why did not they also rewrite the rest? May it be because, when they wrote, the old rules and explanations, with which they did not quarrel in the least, were still well known and used in the original Pāli, or in some closely cognate shape?[i6]

It must have been from some such cognate recension, and not from our Pāli text, that the Govinda story was Sanskritised. The differences between the Dīgha and the Mahāvastu are too great to have arisen at one stage. The whole point of the story in the Dīgha is the way in which Brahmā describes his [258] ideal brahmin as quite emancipated from animistic superstitions and practices. He gains access to Brahmā by practising (with reference, no doubt, to the closing scene of the Mahā-Sudassana, and also to the Tevijjā and other passages) the Rapture of Mercy, one of the Brahma-vihāras, or Sublime Conditions. The Mahāvastu is not satisfied with that. It makes him add to it the kindling of the mystic Fire, Agni (D. II, 239 and Mhvst. III, 210). The paean of delight at the arrival of the new gods (D. II, 227 and Mhvst. III, 203) is introduced in the Mahāvastu by the words: 'He (Brahmā) addressed them in verses.' But it gives only one verse. The others are found in the Dīgha. Perhaps their ethical standpoint did not appeal any more to the Lokottara-vādins. In the eulogy on the Buddha (D. II, 222 and Mhvst. III, 199) the Mahāvastu mentions that there are eight points concerning which the Buddha was worthy of praise. It gives, however, only seven, differing in order and meaning from the eight given in the Dīgha. Verbal differences throughout the whole story are found in almost every paragraph.

In column 136 of Bunyiu Nanjio's catalogue of Chinese Buddhist books we find mentioned a translation of the Mahā-Govinda evidently from some recension different from the Pāli. It would be interesting to know whether there has, in this version, been preserved an intermediate stage between the Dīgha and the Mahāvastu.

The Lord High Steward

[1] Thus have I heard.

The Exalted One was once dwelling in Rājagaha,

on Vulture-peak Hill.

Now when the night was far spent,

Five-crest of the Gandharva fairies,[1]

beautiful to see,

irradiating the whole of Vulture-peak,

came into the presence of the Exalted One,

and saluted him,

and stood on one side.

So standing

Five-crest the Gandharva addressed the Exalted One,

and said:

"The things, lord, that I have seen,

the things I have noted

when in the presence of the gods

in the heaven of the Three-and-Thirty,

I would tell to the Exalted One."

"Tell thou me, Five-crest,"

said the Exalted One.

2. "In days gone by, lord,

in days long long gone by,

on the Fifteenth,

the holy-day,

at the Feast of the Invitations[2]

on the night of full moon,

all the gods in the heaven of the Thirty-Three

were assembled,

sitting in their Hall of Good Counsel.

And a vast celestial company

was seated round about,

and at the four quarters of the firmament

sat the Four Great Kings.

There was Dhataraṭṭha,

king of the East,

seated facing the west,

presiding over his host;

Virūḷhaka,

king of the South,

seated facing the north,

presiding over his host;

Virūpakkha,

king of the West,

seated facing the east,

presiding over his host;

and Vessavaṇa,

king of the North,

seated facing the south,

presiding over his host.

Whenever, lord, all the gods in the heaven of the Thirty-Three

are assembled

and seated in their hall of Good Counsel,

with a vast celestial company

seated around them on every side,

and with the Four Great Kings at the four quarters of the firma- [260] ment,

this is the order of the seats of the Four.

After that come our seats.

And those gods, lord,

who had been recently reborn

in the hosts of the Thirty-Three

because they had lived the higher life

under the Exalted One,

they outshone the other gods

in appearance and in glory.

And thereat, lord,

the Thirty-Three were glad

and of good cheer,

were filled with joy and happiness,

saying:

'Verily, sirs, the celestial hosts are waxing,

the titanic hosts are waning.'

3. Now, lord, Sakka, ruler of the gods,

when he saw the satisfaction

felt by the retinue of the Three-and-Thirty,

expressed his approval in these verses:

'The Three-and-Thirty, verily, both gods and lord, rejoice,

Tathāgata they honour and the cosmic law sublime,

Whereas they see the gods new-risen, beautiful and bright,

Who erst the holy life had lived, under the Happy One,

The Mighty Sage's hearers, who had won to higher truths,

Come hither; and in glory all the other gods outshine.

This they behold right gladly, both lord and Thirty-Three,

Tathāgata they honour and the cosmic law sublime.

Hereat, lord, the Three-and-Thirty Gods

were even more abundantly glad

and of good cheer

and filled with joy and happiness,

saying:

'Verily the celestial hosts are waxing,

the hosts of the titans are waning!'

4. Then Sakka, lord,

perceiving the satisfaction

of the Three-and-Thirty gods,

addressed them thus:

'Is it your wish, gentlemen,

to hear eight truthful items

in praise of that Exalted One?'

'It is our wish, sir,

to hear them.'

Then Sakka, lord, ruler of the gods,

uttered before [261] the Three-and-Thirty gods

these eight truthful items

in praise of the Exalted One:

5. 'Now what think ye, my lords gods Three-and-Thirty?

[1] Inasmuch as the Exalted One has so wrought for the good of the many,

for the happiness of the many,

for the advantage,

the good,

happiness of gods and men,

out of compassion for the world —

a teacher of this kind,

of this character,

we find not,

whether we survey the past

or whether we survey the present —

save only the Exalted One.

■

6. [2] Inasmuch, again,

as the Doctrine has been proclaimed by that Exalted One,

a Doctrine for the life that now is,

a Doctrine not for mere temporary gain,

a Doctrine of welcome and of guidance,

to be comprehended by the wise

each in his own heart —

a preacher of such a Doctrine

so leading us on,

a teacher of this kind,

of this character

we find not,

whether we survey the past,

or whether we survey the present,

save only the Exalted One.

■

7. [3] "This is good;

that is bad" —

well has this been revealed by that Exalted One,

well has he revealed

that this is wrong,

and that is right,

that this is to be followed,

that to be avoided,

that this is base

and that noble,

that this is of the Light

and this of the Dark.[3]

Such a Revelation of the nature of things,

a teacher of this kind,

of this character

we find not,

whether we survey the past,

or whether we survey the present,

save only the Exalted One.

■

8. [4] Well revealed, again, to his disciples

by that Exalted One

is the Way leading to Nirvana;

they run one into the other,

Nirvana and the Way.

Even as the waters of the Ganges and the Jumna

flow one into the other,

and go on together united,

so it is with that well-revealed Way

leading to Nirvana;

they ran one into the other,

Nirvana and the Way.

A revealer of such a Way

leading to Nirvana,

a teacher of this kind,

[262] of this character

we find not,

whether we survey the past,

or whether we survey the present,

save only that Exalted One.

■

9. [5] Comrades too

has this Exalted One gotten,

both students, only travelling along the Way,

and Arahants who have lived "the life."

Them does he not send away,

but dwells in fellowship with them

whose hearts are set on one object.

A teacher so dwelling,

of this kind,

of this character,

we find not,

whether we survey the past,

or whether we survey the present,

save only that Exalted One.

■

10. [6] Well established[4] are the gifts made[5] to that Blessed One,

widely established is his fame,

so much so that the nobles, methinks,

continue well disposed towards him.

Yet notwithstanding,

that Exalted One takes sustenance

with a heart unintoxicated by pride.

One so living,

a teacher of this kind,

of this character,

we find not,

whether we survey the past,

or whether we survey the present,

save only that Exalted One.

■

11. [7] The acts, again, of that Exalted One

conform to his speech;

his speech conforms to his acts.

One who has so carried out hereby

the greater and the lesser matters of the Law,

a teacher of this kind,

of this character,

we find not,

whether we survey the past,

or whether we survey the present;

save only that Exalted One.

■

12. [8] Crossed, too, by that Exalted One

has been the sea of doubt,

gone by for him is all question of the "how"

and "why,"

accomplished for him is every purpose

with respect to his high resolve

and the ancient rule of right.

A teacher who has attained thus far,

of this kind,

of this character,

we find not,

whether we survey the past,

or whether we survey the present,

save only that Exalted One.'

These eight true praises, lord,

of the Exalted One

[263] did Sakka, ruler of the gods, utter before the Three-and-Thirty gods.

Hereat the Three-and-Thirty gods were even more abundantly pleased,

gladdened

and filled with joy and happiness

over the things they had heard.

13. Then certain gods, lord, spoke thus:

'Oh! sir, if only four supreme Buddhas might arise in the world

and teach the Doctrine

even as the Exalted One!

That would make for the welfare of the many,

for the happiness of the many,

for compassion to the world,

for the good

and the gain

and the weal

of gods and men.'

■

And certain other gods spoke thus:

'It would suffice, sir,

if there arose three supreme Buddhas might arise in the world

and teach the Doctrine

even as the Exalted One!

That would make for the welfare of the many,

for the happiness of the many,

for compassion to the world,

for the good

and the gain

and the weal

of gods and men.'

■

And certain other gods spoke thus:

'It would suffice, sir, if two supreme Buddhas might arise in the world

and teach the Doctrine

even as the Exalted One!

That would make for the welfare of the many,

for the happiness of the many,

for compassion to the world,

for the good

and the gain

and the weal

of gods and men.'

14. Then answered Sakka, ruler of the gods

to the Three-and-Thirty:

'Nowhere, gentlemen,

and at no time

is it possible

that, in one and the same world-system,

two Arahant Buddhas supreme should arise together,

neither before

nor after the other.

This can in no wise be.

Ah! gentlemen

would that this Blessed One might yet live for long years to come,

free from disease

and free from suffering!

That would make for the welfare of the many,

for the happiness of the many,

for loving compassion to the universe,

for the good

and the gain

and the weal

of gods and men!'

Then, lord, the Three-and-Thirty gods

having thus deliberated

and taken counsel together

concerning the matter for which they were assembled

and seated in the Hall of Good Counsel,

with respect to that matter

the Four Kings were receivers of the spoken word,

the Four Great Kings were receivers of the admonition given,

remaining the while in their places,

not retiring.[6] [264]

Taking the uttered word and speech,

the Kings Stood there,

serene and calm,

each in his place.

15. Then, lord, from out of the North

came forth a splendid light,

and a radiance shone around,

surpassing the divine glory of the gods.

Then did Sakka, ruler of the gods,

say to the dwellers in the heaven of the Three-and-Thirty:

'According, gentlemen, to the signs now seen,

the light that ariseth,

the radiance that appeareth —

will Brahmā now be made manifest.

For this is the herald sign of the manifestation of Brahmā,

when the light ariseth

and the glory shineth.

Even by yonder signs

great Brahmā draweth nigh.

For this is Brahmāā's sign,

this glorious splendour vast.'

Then, lord, the Three-and-Thirty gods

sat down again in their own places, saying:

'We will ascertain

what shall be the result of this radiance;

when we have realized it,

we will go to meet him.'

The Four Kings also sat down in their places,

saying:

'We will ascertain

what shall be the result of this radiance;

when we have realized it,

we will go to meet him.'

And when they heard that,

the Three-and-Thirty gods were all agreed saying:

'We will ascertain

what shall be the result of this radiance;

when we have realized it,

we will go to meet him.'

16. When, lord, Brahmā Sanaṃkumāra appears before the Thirty-Three gods,

he manifest himself as an individual of relatively gross substance

which he has specially created.

For Brahmā's usual appearance

is not sufficiently materialized

for the scope of the sight of the Thirty-Three Gods.

And, lord, when Brahmā Sanaṃkumāra is manifested before the Thirty-Three Gods,

he outshines the other gods

in his appearance and his glory.

Just, lord, as a figure made of gold

outshines the human frame,

so, when Brahmā Sanaṃkumāra is manifested before the Thirty-Three Gods,

does he outshine the other gods

in his appearance and his glory.

And when, lord, Brahmā Sanaṃkumāra is manifested [265] before the Thirty-Three Gods,

not one god in that assembly salutes him,

or rises up,

or invites him to be seated.

They all sit in silence,

with clasped hands

and cross-legged,

thinking:

'Of whichever god Brahmā Sanaṃkumāra now desires anything,

he will sit down on that god's divan.'

And that god by whom he does so seat himself,

is filled with a sublime satisfaction,

a sublime happiness,

even as a Kshatriya king

newly anointed and crowned

is filled with a sublime satisfaction,

a sublime happiness.

17. Then, lord, Brahmā Sanaṃkumāra perceiving how gratified were those Three-and-Thirty gods,

uttered his approval in these verses:

'The Three-and-Thirty, verily, both gods and lord, rejoice,

Tathāgata they honour and the cosmic law sublime,

Whereas they see these gods new-risen, beautiful and bright,

Who erst the holy life had lived, under the Happy One,

The Mighty Sage's hearers, who had won to higher truths,

Come hither; and in glory all the other gods outshine.

This they behold right gladly, both lord and Thirty-Three,

Tathāgata they honour and the cosmic law sublime.'

18. This was the matter of Brahmā Sanaṃkumāra's speech.

And he spoke it with a voice of eightfold quality —

in a voice that was fluent,

intelligible,

sweet,

audible,

sustained,

distinct,

deep,

and resonant.

And whereas, lord, Brahmā Sanaṃkumāra

made himself audible to that assembly by his voice,

the sound thereof did not penetrate beyond the assembly.

He whose voice has these eight characteristics

is said to have a Brahmā-voice.

19. Then, lord, to Brahmā the Eternal Youth

the Three-and-Thirty gods spoke thus:

'Tis well, O Brahmā!

we do rejoice at this that we have noted.

Moreover Sakka, ruler of the gods,

[266] hath rehearsed to us

eight truthful praises of that Exalted One,

and these too we have marked and do rejoice thereat.'

Then, lord, Brahmā the Eternal Youth spoke thus

to Sakka, ruler of the gods:

'Tis well, O ruler of the gods;

we too would hear the eight truthful praises of that Exalted One.'

'So be it, O Great Brahmā,'

replied Sakka.[7]

20. 'Now what think ye, my lord, the Great Brahmā?

Inasmuch as the Exalted One has so wrought for the good of the many,

for the happiness of the many,

for the advantage,

the good,

happiness of gods and men,

out of compassion for the world —

a teacher of this kind,

of this character,

we find not,

whether we survey the past

or whether we survey the present —

save only the Exalted One.

21. Inasmuch, again,

as the Doctrine has been proclaimed by that Exalted One,

a Doctrine for the life that now is,

a Doctrine not for mere temporary gain,

a Doctrine of welcome and of guidance,

to be comprehended by the wise

each in his own heart —

a preacher of such a Doctrine

so leading us on,

a teacher of this kind,

of this character

we find not,

whether we survey the past,

or whether we survey the present,

save only the Exalted One.

22. "This is good;

that is bad" —

well has this been revealed by that Exalted One,

well has he revealed

that this is wrong,

and that is right,

that this is to be followed,

that to be avoided,

that this is base

and that noble,

that this is of the Light

and this of the Dark.

Such a Revelation of the nature of things,

a teacher of this kind,

of this character

we find not,

whether we survey the past,

or whether we survey the present,

save only the Exalted One.

23. Well revealed, again, to his disciples

by that Exalted One

is the Way leading to Nirvana;

they run one into the other,

Nirvana and the Way.

Even as the waters of the Ganges and the Jumna

flow one into the other,

and go on together united,

so it is with that well-revealed Way

leading to Nirvana;

they ran one into the other,

Nirvana and the Way.

A revealer of such a Way leading to Nirvana,

a teacher of this kind,

of this character

we find not,

whether we survey the past,

or whether we survey the present,

save only that Exalted One.

24. Comrades too

has this Exalted One gotten,

both students, only travelling along the Way,

and Arahants who have lived "the life."

Them does he not send away,

but dwells in fellowship with them

whose hearts are set on one object.

A teacher so dwelling,

of this kind,

of this character,

we find not,

whether we survey the past,

or whether we survey the present,

save only that Exalted One.

25. Well established are the gifts made to that Blessed One,

widely established is his fame,

so much so that the nobles, methinks,

continue well disposed towards him.

Yet notwithstanding,

that Exalted One takes sustenance

with a heart unintoxicated by pride.

One so living,

a teacher of this kind,

of this character,

we find not,

whether we survey the past,

or whether we survey the present,

save only that Exalted One.

26. The acts, again, of that Exalted One

conform to his speech;

his speech conforms to his acts.

One who has so carried out hereby

the greater and the lesser matters of the Law,

a teacher of this kind,

of this character,

we find not,

whether we survey the past,

or whether we survey the present;

save only that Exalted One.

27. Crossed, too, by that Exalted One

has been the sea of doubt,

gone by for him is all question of the 'how'

and 'why,'

accomplished for him is every purpose

with respect to his high resolve

and the ancient rule of right.

A teacher who has attained thus far,

of this kind,

of this character,

we find not,

whether we survey the past,

or whether we survey the present,

save only that Exalted One.'

These eight true praises, lord,

of the Exalted One

did Sakka, ruler of the gods, utter before the Great Brahmā.

Hereat, lord, Brahmā the Eternal Youth was pleased and gladdened,

and was filled with joy and happiness

when he had heard those praises.

28. And so, lord, Brahmā the Eternal Youth materializing himself and becoming in appearance like the youth Five-crest,

manifested himself to the Three-and-Thirty gods,

and rising up into the air,

he sat down cross-legged in the sky.

Just, lord, as easily as a strong man

might sit down cross-legged on a well-spread divan

or a smooth piece of ground,

even so did Brahmā the Eternal Youth,

rising up into the air,

sit down cross-legged in the sky.

And he addressed the Three-and-Thirty gods thus:

29. 'Now what think ye, my lord gods Thirty-and-Three?

For how long hath the Blessed One been of great wisdom?[8]

Once upon a time there was a king named Disampati.

And king Disampati's minister was a brahmin named Govinda (the Steward).[9]

And king Disampati had a son named Reṇu,

and Govinda had a son named Jotipāla.

And prince Reṇu

and the young Jotipāla

and six other young nobles —

these eight—were great friends.

Now in the course of years Govinda [267] died.

And king Disampati mourned for him, saying:

"Alas! just when we had devolved all our duties on Govinda the brahmin,

and were surrounded by

and giving ourselves up to

the pleasures of sense,

Govinda has died!"

Then said prince Reṇu to the king:

"Mourn not, sire, so excessively for Govinda, the brahmin.

Govinda has a son,

young Jotipāla,

who is wiser than his father was,

better able to see what is profitable than his father.

Let Jotipāla administer all such affairs

as were entrusted to his father."

"Do you think so, my boy?"

"I do, sire."

30. Then king Disampati summoned a man and said:

"Come you, good man,

go to Master Jotipāla, and say to him:

'May good fortune attend the honourable Jotipāla!

King Disampati calls for the honourable Jotipāla.

King Disampati would like to see the honourable Jotipāla.'

"So be it, sire,"

responded the man,

and going to Jotipāla he repeated the message.

"Very good, sir,"

responded Jotipāla,

and went to wait upon the king.

And when he had come into the king's presence,

he exchanged with the king the greetings and compliments of politeness and courtesy,

and sat down on one side.

Then said king Disampati to Jotipāla:

"We would have the honourable youth Jotipāla administer for us.

Let him not refuse to do so.

I will set him in his father's place

and appoint him to the Stewardship."[10]

"So be it, sire,"

replied Jotipāla in assent.

31. So king Disampati appointed Jotipāla as his Steward,

and set him in his father's place.

And thus appointed and installed,

whatever matters his father had administered,

those did Jotipāla administer;

and [268] whatever his father had not administered,

those matters did he too not administer.

And whatever works his father had accomplished,

and no others,

even such works,

and no others,

did he too accomplish.

Of him men said:

"The brahmin is verily a Steward!

A Great Steward is verily this brahmin!"

And on this wise Jotipāla came to be called the High Steward.

32. Now it came to pass that the Great Steward went to those six nobles,

and said to them:

"Disampati the king is old

and wasted with age,

full of years,

and arrived at the term of life.

Who indeed can answer for the survival of the living?

When the king dies,

it will behove the king-makers to anoint Reṇu the prince as king.

I suggest, gentlemen,

that you wait on prince Reṇu,

and say to him thus:

'We are the dear, beloved, and congenial friends of our lord Reṇu.

We are happy when our lord is happy;

unhappy when he is unhappy.

Disampati, our lord king,

is old and wasted with age,

full of years and arrived at the term of life.

Who indeed can answer for the living?

When the king dies,

it will behove the kingmakers

to anoint our lord Reṇu king.

If our lord Reṇu should gain the sovereignty,

let him divide it with us.'

33. "So be it,"

responded the six nobles,

and waiting upon prince Reṇu

they repeated these words to him.

"Why, sirs, who besides myself

ought to prosper in this realm

if it be not you?

If I, sirs, shall gain the sovereignty,

I will divide it with you."

34. And it came to pass in course of time

that king Disampati died.

And after his death,

the kingmakers anointed Reṇu his son king.

And he, when he was made king,

lived surrounded by

and given up to

the pleasures of sense.

Then the High Steward went to those six nobles and said thus:

"Disampati, gentlemen, is dead,

and my lord Reṇu lives surrounded by

and given up to

the pleasures of sense.

Well, gentlemen, who can say?

The pleasures of sense are intoxicating,

I would suggest, gentlemen,

[269] that you wait on king Reṇu

and say to him:

'King Disampati, my lord, is dead,

my lord Reṇu is anointed king.

Does my lord remember his promise?'"

"Very good, sir,"

responded the six nobles,

and going into Reṇu's presence,

they said:

"King Disampati, sire, is dead,

and my lord Reṇu is anointed king.

Does my lord remember his promise?"

"I do remember my promise, gentlemen.

Which of you gentlemen now

is able successfully to divide this mighty [land

so broad on the north end,

Sakaṭamukka[11] on the south,

into seven equal portions?"

"Who, sire, is able

if it be not the Great Steward, the brahmin?"

55. Then king Reṇu sent a man to the Great Steward, saying:

"Come, my good fellow,

go to the Great Steward, the brahmin, and say:

'The king has sent for you, my lord.'"

And the Great Steward was told and obeyed,

and, coming into the king's presence,

exchanged with him the greetings and compliments of politeness and courtesy,

and sat down on one side.

Then said the king to him:

"Will you go, my lord Steward,

and so divide this great [land

so broad at the north end,

as narrow at the south as the pole of a bull cart,]

into seven portions, all equal."

"Very good, sire,"

responded the High Steward,

and he so divided this great [land

so broad at the north end,

as narrow at the south as the pole of a bull cart,]

into seven portions, all equal.

36. And king Reṇu's country held the central position.

As it is said:

[270] Dantapura of the Kālingas, and Potana for the Assakas,

Māhissati for the Avantis, and Roruka in the Sovira land.

Mithila of the Videhās, and then Campā among the Aṇgas,

Lastly Benares in the Kāsi realm: — all these did the Great Steward wisely plan.

Then were those six nobles well pleased each with his allotted gain,

and at the success of his plan.

For they said:

"What we wished for,

what we desired,

what we intended,

what we aimed at,

lo! that is what we have gotten."

And the seven kings were named:

Sattabhu and Brahmādatta,

Vessabhu with Bharata,

Reṇu and two Dhaṭaraṭṭhas:

These are the seven Bharatas.[12]

§

Here ends the first Portion for Recitation.

Chapter II

[271] 37. Now those six nobles came to the High Steward and said to him:

"Just as the honourable Steward

was dear, beloved and congenial

as companion to Reṇu the king,

so has he been also to us a companion,

dear, beloved and congenial.

We would that the honourable Steward administer our affairs;

we trust he will not refuse to do so."

"Very good, sirs"

replied the Great Steward.

And so he instructed those seven anointed kings in government;

and he taught the mantras to seven eminent and wealthy Brahmāns

and to seven hundred young graduates.

38. Now later on

the excellent reputation of the brahmin, the High Steward,

was noised abroad after this fashion:

"With his own eyes

the High Steward sees Brahmā!

Face to face

does the High Steward commune with Brahmā,

converse and take counsel with Him!"

Then the High Steward thought:

"This flattering rumour is noised abroad about me,

that I both see Brahmā

and hold converse with Him.

Now I neither see Him,

nor commune with Him,

nor converse

or take counsel with Him.

But I have heard aged and venerable brahmins,

teachers and pupils, say:

'He who remains in meditation the four months of the rains,

and practises the ecstasy of pity,

he sees Brahmā,

communes,

converses,

takes counsel with Brahmā.'

What if I now were to cultivate that discipline?"

39. So the High Steward waited on king Reṇu,

and telling him:

"This flattering rumour is noised abroad about me,

that I both see Brahmā

and hold converse with Him.

Now I neither see Him,

nor commune with Him,

nor converse

or take counsel with Him.

But I have heard aged and venerable brahmins,

teachers and pupils, say:

'He who remains in meditation the four months of the rains,

and practises the ecstasy of pity,

he sees Brahmā,

communes,

converses,

takes counsel with Brahmā.'

I wish, sir, to meditate

during the four months of the rains

and to practise the ecstasy of pity.

No one is to come near me

save some one who will bring me my meals."

"Do, honourable Steward, whatever seems to you fit."

40. And the High Steward went round to each of the six nobles,

and told them:

"This flattering rumour is noised abroad about me,

that I both see Brahmā

and hold converse with Him.

Now I neither see Him,

nor commune with Him,

nor converse

or take counsel with Him.

But I have heard aged and venerable brahmins,

teachers and pupils, say:

'He who remains in meditation the four months of the rains,

and practises the ecstasy of pity,

he sees Brahmā,

communes,

converses,

takes counsel with Brahmā.'

I wish, sir, to meditate

during the four months of the rains

and to practise the ecstasy of pity.

No one is to come near me

save some one who will bring me my meals."

"Do, honourable Steward, whatever seems to you fit."

41. Then he went to those seven eminent and wealthy Brahmāns,

and to the seven hundred graduates, [272]

and told them:

"This flattering rumour is noised abroad about me,

that I both see Brahmā

and hold converse with Him.

Now I neither see Him,

nor commune with Him,

nor converse

or take counsel with Him.

But I have heard aged and venerable brahmins,

teachers and pupils, say:

'He who remains in meditation the four months of the rains,

and practises the ecstasy of pity,

he sees Brahmā,

communes,

converses,

takes counsel with Brahmā.'

Wherefore, sirs, according as you have heard the mantras

and have committed them to memory,

continue to rehearse them in full,

and teach them to each other.

I, sirs, wish to meditate during the four months of the rains,

and to practise the ecstasy of pity.

No one is to come near me

save some one who shall bring me my meals."

"Do, honourable Steward, whatever seems to you fit."

42. Next the High Steward went to his forty wives

who were all on an equality,

and told them:

"This flattering rumour is noised abroad about me,

that I both see Brahmā

and hold converse with Him.

Now I neither see Him,

nor commune with Him,

nor converse

or take counsel with Him.

But I have heard aged and venerable brahmins,

teachers and pupils, say:

'He who remains in meditation the four months of the rains,

and practises the ecstasy of pity,

he sees Brahmā,

communes,

converses,

takes counsel with Brahmā.'

I, sisters, wish to meditate during the four months of the rains,

and to practise the ecstasy of pity.

No one is to come near me

save some one who shall bring me my meals."

"Do, honourable Steward, whatever seems to you fit."

43. Then the High Steward had a new rest-house built eastward of the city,

and there for the four months of the rains he meditated,

rapt in the Ecstasy of Pity;

nor did any one have access to him

save one who brought him his meals.

But when the four rainy months were over,

then verily came disappointment and anguish over him

as he thought:

"Here have I heard aged and venerable brahmins,

teachers and their pupils, say:

'He who remains in meditation the four months of the rains,

and practises the Ecstasy of Pity,

he sees Brahmā,

communes,

converses,

and takes counsel with Brahmā.'

But I see not Brahmā,

I commune not,

nor converse,

nor take counsel with Him."

44. Then Brahmā, the Eternal Youth,

when in his mind

he knew the thoughts of the High Steward's mind,

vanished from his heaven,

and, like a strong man shooting his arm out

or drawing back his out-shot arm,

appeared before the High Steward.

Then verily came fear,

then came trembling

upon the High Steward,

then did the hair of his flesh stand up[13]

when he saw this thing that had never been seen before.

And he,

full of fear and dread

with stiffening hair,

addressed Brahmā the Eternal Youth in these verses:

[273] "O Vision fair, O glorious and divine!

Who art thou, lord? knowing thee not we ask,

That we may know!

In heaven supreme I'm known

As the Eternal Youth. All know me there.

Know me e'en thou, Govinda.

To a Brahmā Blest

Let seat and water for the feet and sweet

Cooked cakes and drink be brought. We ask what gift

The Lord would take. Would he himself decide

The form for us.[14]

Hereby we take thy gift,

And now — whether it be for good and gain

In this thy present life, or for thy weal

In that which shall be — Thou hast leave. Come, ask,

Govinda, whatsoe'er thou fain would'st have?"

45. Then the High Steward thought:

"Leave is given me by Brahmā the Eternal Youth!

What now shall I ask of him,

some good thing for this life,

or a future good?"

Then it occurred to him:

"I am an expert regarding what is profitable for this life.

Even others consult me about that.

What now if I were to ask Brahmā the Eternal Youth

for something of advantage in a life to come?"

And he addressed the god in these verses:

"I ask the Brahmā, the Eternal Youth,

Him past all doubt I, doubting, ask anent

The things that others would fain know about.

Wherein proficient, in what method trained

Can mortal reach th'immortal world of Brāhm?"

[274] "He among men, O Brahmān, who eschews

All claims of 'me' and 'mine'; he in whom thought

Rises in lonely calm, in pity rapt,

Loathing all foul things, dwelling in chastity, —

Herein proficient, in such matters trained,

Mortal can reach th'immortal heaven of Brāhm."

46. "What the Lord saith touching

'eschewing all claims of "me" and "mine"'

I understand.

It is to renounce all property

whether it be small or large,

and to renounce all family life,

whether the circle of one's kin be small or large,

and with hair and beard cut off

and yellow robes donned,

to go forth from the home into the homeless life.

Thus do I understand this.

What the Lord saith touching

'thought rising in lonely calm'

I understand.

It is when one chooses a solitary abode —

the forest,

at the foot of a tree,

a mountain brae,

a grotto,

a rock-cavern,

a cemetery,

or a heap of grass out in the open field.

Thus do I understand this.

What the Lord saith touching

'in pity rapt'

I understand.

It is when one continues to pervade

one quarter of the horizon

with a heart charged with pity,

and so the second quarter,

and so the third,

and so the fourth.

And thus the whole wide world,

above,

below,

around and everywhere

does one continue to pervade

with a heart charged with pity,

far-reaching,

expanded,

infinite,

free from wrath and ill will.

Thus do I understand this.

Only in what He saith touching

'loathing the foul'

do I not understand thee, Lord.

What mean'st thou by

'foul odours among men,'

O Brahmā? here I understand thee not.

Tell what these signify, who knowest all.

When cloaked and clogged by what is man thus foul.

Hell-doomed, and shut off from the heaven of Brāhm?"

"Anger and lies, deceit and treachery,

Selfishness, self-conceit and jealousy,

[275] Greed, doubt, and lifting hands 'gainst fellow men,

Lusting and hate, dullness and pride of life, —

When yoked with these man is of odour foul,

Hell-doomed, and shut out from the heaven of Brāhm."

As I understand the word of the Lord concerning these

'foul odours,'

they cannot easily be suppressed

if one live in the world.

I will therefore go forth from the home

into the life of the homeless state."

"Do, lord steward, whatever seems to you fit."

47. Then the High Steward waited on king Reṇu

and said to him:

"Will my lord now seek another minister,

who will administer my lord's affairs?

I wish to leave the world

for the homeless life.

I am going forth

in accordance with the word of Brahmā

which I have heard

concerning foul odours.

These cannot be easily suppressed

when one is living in the world.

King Reṇu, lord o' the land, I here declare: —

Do thou thyself take thought for this thy realm!

I care no longer for my ministry."

"If for thy pleasures aught there lacketh yet,

I'll make it good. If any injure thee,

Them I'll restrain, warlord and landlord I!

Thou art my father, Steward, lo! I am thy son!

Abide with us, Govinda, leave us not."

"Naught lack I for my pleasures, nor is there

One who doth injure me. But I have heard

Voices unearthly. Henceforth home holds me not."

"What like is this Unearthly? What did He say

To thee, that having heard thou will straightway

Forsake our house and us and all the world?"

"Ere I had passed through this Retreat, my care

Was for due altar-rites, the sacred fire

Was kindled, strewn about with kusa-grass.

But lo! Brahmā I saw, from Brahmā's heaven,

Eternal god. I asked; he made reply;

I heard. And now irksome is home to me."

[276] "Lo! I believe the words that thou hast said.

Govinda. Having heard the Unearthly Voice.

How could it be thou should'st act otherwise?

Thee will we follow after. Be our guide,

Our teacher! So, like gem of purest ray,

Purg'd of all dross, translucent, without flaw, —

As pure as that we'll walk according to thy word.

If the honourable Steward goes forth

from the home into the homeless,

I too will do the like.

For whither thou goest, I will go."

48. Then the High Steward, the brahmin,

waited upon the six nobles,

and said to them:

"Will my lords now seek another minister who will administer my lords' affairs?

I wish to leave the world for the homeless life.

I am going forth

in accordance with the word of Brahmā

which I have heard concerning foul odours.

These cannot be easily suppressed

when one is living in the world."

Then the six nobles went aside together

and thus deliberated:

"These brahmin folk are greedy for money.

What if we were to gain him over through money?"

And coming to the High Steward they said:

"There is abundance of property, sir,

in these seven kingdoms.

Wherefore, sir, take of it as much as seems profitable to you."

"Enough, sirs!

I have already abundant possessions,

thanks to the action of my lords.

It is that luxury

that I am now relinquishing

in leaving the world

for the homeless life.

I am going forth

in accordance with the word of Brahmā

which I have heard concerning foul odours.

These cannot be easily suppressed

when one is living in the world."

49. Then the six nobles went aside together,

and thus deliberated:

"These brahmin folk are greedy about women.

What if we were to gain him over through women?"

And coming to the High Steward they said:

"There is, sir, in those seven kingdoms abundance of women.

Wherefore, sir, conduct away with you as many as you want."

"Enough, sirs!

I have already these forty wives

equal in rank.

All of them I am forsaking

in leaving the world for the homeless life.'

I am going forth

in accordance with the word of Brahmā

which I have heard concerning foul odours.

These cannot be easily suppressed

when one is living in the world."

[277] 50. "If the honourable Steward goes forth

from the home into the homeless life,

we too will do the like.

Whither thou goest we will go.

If ye would put off fleshly lusts that worldling's heart coerce,

Stir ye the will, wax strong, firm in the power of patience.

This is the Way, the Way that's Straight,[15] the Way unto the End,[16]

The Righteous Path that good men guard, to birth in Brahmā's heaven.

51. Wherefore, my lord Steward, wait yet seven years,

and when they are over,

we too will go forth from the world

into the homeless life.

Whither thou goest we will go."

"Too long, my lords, are seven years!

I cannot wait for my lords seven years.

For who can answer for the living?[17]

We must go toward the future,

we must learn by wisdom,[18]

we must do good,

we must walk in righteousness,

for there is no escaping death

for all that's born.

Now I am going forth

in accordance with the word of Brahmā

which I have heard concerning foul odours.

They cannot be easily suppressed

when one is living in the world."

■

52. "Well then, lord Steward, wait for us six years,

and when they are over,

we too will go forth from the world

into the homeless life.

Whither thou goest we will go."

"Too long, my lords, are six years!

I cannot wait for my lords six years.

For who can answer for the living?

We must go toward the future,

we must learn by wisdom,

we must do good,

we must walk in righteousness,

for there is no escaping death

for all that's born.

Now I am going forth

in accordance with the word of Brahmā

which I have heard concerning foul odours.

They cannot be easily suppressed

when one is living in the world."

■

"Well then, lord Steward, wait for us five years,

and when they are over,

we too will go forth from the world

into the homeless life.

Whither thou goest we will go."

"Too long, my lords, are five years!

I cannot wait for my lords five years.

For who can answer for the living?

We must go toward the future,

we must learn by wisdom,

we must do good,

we must walk in righteousness,

for there is no escaping death

for all that's born.

Now I am going forth

in accordance with the word of Brahmā

which I have heard concerning foul odours.

They cannot be easily suppressed

when one is living in the world."

■

"Well then, lord Steward, wait for us four years,

and when they are over,

we too will go forth from the world

into the homeless life.

Whither thou goest we will go."

"Too long, my lords, are four years!

I cannot wait for my lords four years.

For who can answer for the living?

We must go toward the future,

we must learn by wisdom,

we must do good,

we must walk in righteousness,

for there is no escaping death

for all that's born.

Now I am going forth

in accordance with the word of Brahmā

which I have heard concerning foul odours.

They cannot be easily suppressed

when one is living in the world."

■

"Well then, lord Steward, wait for us three years,

and when they are over,

we too will go forth from the world

into the homeless life.

Whither thou goest we will go."

"Too long, my lords, are three years!

I cannot wait for my lords three years.

For who can answer for the living?

We must go toward the future,

we must learn by wisdom,

we must do good,

we must walk in righteousness,

for there is no escaping death

for all that's born.

Now I am going forth

in accordance with the word of Brahmā

which I have heard concerning foul odours.

They cannot be easily suppressed

when one is living in the world."

■

"Well then, lord Steward, wait for us two years,

and when they are over,

we too will go forth from the world

into the homeless life.

Whither thou goest we will go."

"Too long, my lords, are two years!

I cannot wait for my lords two years.

For who can answer for the living?

We must go toward the future,

we must learn by wisdom,

we must do good,

we must walk in righteousness,

for there is no escaping death

for all that's born.

Now I am going forth

in accordance with the word of Brahmā

which I have heard concerning foul odours.

They cannot be easily suppressed

when one is living in the world."

■

"Well then, lord Steward, wait for us one year,

and when they are over,

we too will go forth from the world

into the homeless life.

Whither thou goest we will go."

53. "Too long, my lords, is one year!

I cannot wait for my lords one year.

For who can answer for the living?

We must go toward the future,

we must learn by wisdom,

we must do good,

we must walk [278] in righteousness,

for there is no escaping death

for all that's born.

Now I am going forth

in accordance with the word of Brahmā

which I have heard concerning foul odours.

They cannot be easily suppressed

when one is living in the world."

■

"Well then, lord Steward, wait for us seven months,

and when they are over,

we too will go forth from the world

into the homeless life.

Whither thou goest we will go."

53. "Too long, my lords, is seven months!

I cannot wait for my lords seven months.

For who can answer for the living?

We must go toward the future,

we must learn by wisdom,

we must do good,

we must walk in righteousness,

for there is no escaping death

for all that's born.

Now I am going forth

in accordance with the word of Brahmā

which I have heard concerning foul odours.

They cannot be easily suppressed

when one is living in the world."

■

"Well then, lord Steward, wait for us six months,

and when they are over,

we too will go forth from the world

into the homeless life.

Whither thou goest we will go."

53. "Too long, my lords, is six months!

I cannot wait for my lords six months.

For who can answer for the living?

We must go toward the future,

we must learn by wisdom,

we must do good,

we must walk in righteousness,

for there is no escaping death

for all that's born.

Now I am going forth

in accordance with the word of Brahmā

which I have heard concerning foul odours.

They cannot be easily suppressed

when one is living in the world."

■

"Well then, lord Steward, wait for us five months,

and when they are over,

we too will go forth from the world

into the homeless life.

Whither thou goest we will go."

53. "Too long, my lords, is five months!

I cannot wait for my lords five months.

For who can answer for the living?

We must go toward the future,

we must learn by wisdom,

we must do good,

we must walk in righteousness,

for there is no escaping death

for all that's born.

Now I am going forth

in accordance with the word of Brahmā

which I have heard concerning foul odours.

They cannot be easily suppressed

when one is living in the world."

■

"Well then, lord Steward, wait for us four months,

and when they are over,

we too will go forth from the world

into the homeless life.

Whither thou goest we will go."

53. "Too long, my lords, is four months!

I cannot wait for my lords four months.

For who can answer for the living?

We must go toward the future,

we must learn by wisdom,

we must do good,

we must walk in righteousness,

for there is no escaping death

for all that's born.

Now I am going forth

in accordance with the word of Brahmā

which I have heard concerning foul odours.

They cannot be easily suppressed

when one is living in the world."

■

"Well then, lord Steward, wait for us three months,

and when they are over,

we too will go forth from the world

into the homeless life.

Whither thou goest we will go."

53. "Too long, my lords, is three months!

I cannot wait for my lords three months.

For who can answer for the living?

We must go toward the future,

we must learn by wisdom,

we must do good,

we must walk in righteousness,

for there is no escaping death

for all that's born.

Now I am going forth

in accordance with the word of Brahmā

which I have heard concerning foul odours.

They cannot be easily suppressed

when one is living in the world."

■

"Well then, lord Steward, wait for us two months,

and when they are over,

we too will go forth from the world

into the homeless life.

Whither thou goest we will go."

53. "Too long, my lords, is two months!

I cannot wait for my lords two months.

For who can answer for the living?

We must go toward the future,

we must learn by wisdom,

we must do good,

we must walk in righteousness,

for there is no escaping death

for all that's born.

Now I am going forth

in accordance with the word of Brahmā

which I have heard concerning foul odours.

They cannot be easily suppressed

when one is living in the world."

■

"Well then, lord Steward, wait for us one month,

and when they are over,

we too will go forth from the world

into the homeless life.

Whither thou goest we will go."

53. "Too long, my lords, is one month!

I cannot wait for my lords one month.

For who can answer for the living?

We must go toward the future,

we must learn by wisdom,

we must do good,

we must walk in righteousness,

for there is no escaping death

for all that's born.

Now I am going forth

in accordance with the word of Brahmā

which I have heard concerning foul odours.

They cannot be easily suppressed

when one is living in the world."

■

"Well then, lord Steward, wait for us half a month,

and when they are over,

we too will go forth from the world

into the homeless life.

Whither thou goest we will go."

53. "Too long, my lords, is half a month!

I cannot wait for my lords half a month.

For who can answer for the living?

We must go toward the future,

we must learn by wisdom,

we must do good,

we must walk in righteousness,

for there is no escaping death

for all that's born.

Now I am going forth

in accordance with the word of Brahmā

which I have heard concerning foul odours.

They cannot be easily suppressed

when one is living in the world."

■

"Well then, lord Steward, wait for us seven days,

till we have devolved our kingdoms

on to our sons and brothers.

When seven days are over,

we will leave the world for the Homeless State.

Whither thou goest we will go."

"Seven days, my lords,

is not a long time.

I will wait, my lords, for seven days."

56. Then the High Steward, the brahmin,

came to those seven eminent and wealthy brahmins

and to those seven hundred graduates,

and said:

"Will ye now seek another teacher, sirs,

who will (by repetition) teach you the mystic verses?[19]

I wish to leave the world

for the homeless life.

I am going forth in accordance with the word of Brahmā

which I have heard concerning foul odours.

These cannot easily be suppressed

when one is living in the world."

"Let the honourable Steward not leave the world for the homeless life!

Leaving the world means little power

and little gain;

to be a brahmin brings great power

and great gain."

"Speak not so, gentlemen,

of leaving the world

or of being a brahmin.

Who for that matter has greater power or wealth than I?

I, sirs, have been hitherto as a king of kings,

as Brahmā to brahmins,

as a deity[20] to householders.

And this,

all this,

I put away

in leaving the world,

in accordance with the word of Brahmā

which I have heard concerning foul odours.

These cannot easily be suppressed

when one is living in the world."

"If the lord Steward leaves the world for the Homeless State,

we too will do the like.

Whither thou goest, we will go."

[279] 57. Then the High Steward, the Brahmān,

went to his forty wives,

all on an equality,

and said:

"Will each of you, ladies,

who may wish to do so,

go back to her own family

and seek another husband?

I wish, ladies, to leave the world

for the homeless life, in accordance with the of Brahmā

which I have heard concerning foul odours.

These cannot easily be suppressed

when one is living in the world."

"Thou, even thou,

art the kinsman of our hearts' desire;

thou art the husband of our hearts' desire.

If the lord Steward leaves the world for the Homeless State,

we too will do the like.

Whither thou goest, we will go."

58. And so the High Steward, the brahmin,

when those seven days were past,

let his hair and beard be cut off,

donned the yellow robes

and went forth from his home into the Homeless State.

And he having so acted,

the seven kings also,

anointed kshatriyas,

as well as the seven eminent and wealthy brahmins

and the seven hundred graduates,

the forty wives all on an equality,

several thousand nobles,

several thousand brahmins,

several thousand commoners

and several young women from women's quarters,

let their hair be cut,

donned the yellow robes

and went forth from their homes

into the Homeless State.

And so, escorted by this company,

the High Steward, the brahmin,

went a-wandering through the villages,

towns,

and cities.

And whether he arrived at village or town or city,

there he became as a king to kings,

as Brahmā to brahmins,

as a deity to commoners.

And in those days when any one sneezed or slipped,

they called out:

"Glory be to the High Steward, the brahmin!

Glory be to the Minister of Seven!"

59. Now the High Steward, the brahmin,

continued to pervade one quarter of the world with thoughts of Love;

and so the second quarter,

and so the third,

and so the fourth.

And thus the whole wide world,

above,

below,

around,

and everywhere,

did he continue to pervade with heart of Love,

far-reaching,

grown great,

and beyond measure,

free from the least trace of anger or ill-will.

■

And he let his mind pervade one quarter of the world with thoughts of Pity;

and so the second quarter,

and so the third,

and so the fourth.

And thus the whole wide world,

above,

below,

around,

and everywhere,

did he continue to pervade with heart of Pity,

far-reaching,

grown great,

and beyond measure,

free from the least trace of anger or ill-will.

■

And he let his mind pervade one quarter of the world with thoughts of Sympathy;

and so the second quarter,

and so the third,

and so the fourth.

And thus the whole wide world,

above,

below,

around,

and everywhere,

did he continue to pervade with heart of Sympathy,

far-reaching,

grown great,

and beyond measure,

free from the least trace of anger or ill-will.

■

And he let his mind pervade one quarter of the world with thoughts of Equanimity;

and so the second quarter,

and so the third,

and so the fourth.

And thus the whole wide world,

above,

below,

around,

and everywhere,

did he continue to pervade with heart of Sympathy,

far-reaching,

grown great,

and beyond measure,

free from the least trace of anger or ill-will.

And he taught to disciples

the way to union with the world of Brahmā.

[280] 60. Now all they who at that time

had been the High Steward's disciples

and in all points wholly understood his teaching,

were after their death

reborn into the blissful world of Brahmā.

They who had not in all points

wholly understood his teaching,

were after their death

reborn into the company either of

the gods who Dispose of Joys purveyed from without,

or of the gods of the Heaven of Boundless Delight,

or of the gods of the Heavens of Bliss,

or of the Yāma gods,

or of the Three-and-Thirty gods,

or of the gods who are the Four Kings of the Horizon.

Even they who accomplished the lowest realm of all,

attained to the realm of the Gandharva fairies.

Thus of all those clansmen

there was not one whose renunciation proved vain or barren;

in each case it bore fruit and development.'

§

61. Does the Exalted One remember?"

"I do remember, Five-crest.

I was the High Steward of those days.[21]

I taught my disciples the way to communion with the Brahmā world.

But, Five-crest,

that religious life

did not conduce to detachment,

to passionlessness,

to cessation of craving,

to peace,

to understanding,

to insight of the higher stages of the Path,

to Nirvana,

but only to rebirth in the Brahmā-world.

On the other hand

my religious system, Five-crest,

conduces wholly and solely to detachment,

to passionlessness,

to cessation of craving,

to peace,

to understanding,

to insight of the higher stages of the Path,

to Nirvana.

And that is the Aryan Eightfold Path, to wit,

right views,

right intention,

right speech,

right, action,

right livelihood,

right effort,

right mindfulness,

right rapture.

62. Those of my disciples, Five-crest,

who in all points

wholly understand my teaching,

they from the [281] destruction of the Deadly Taints

have by and for themselves understood,

realized

and attained to,

even in this life,

freedom from taint,

liberty of heart,

liberty of intellect.

Those who do not in all points

wholly understand my teaching,

some of them,

in that they have broken away the five Fetters belonging to the Hither Side,

are reborn without parents,

where they will utterly pass away,

being no more liable to return to this world.

And some of them,

in that they have broken away three [other] Fetters,

and have worn down passion and hate and dullness,

become Once-Returners,

who after once returning to this world

shall make an end of I11.

And some of them, again,

in that they have broken away those three Fetters,

become Stream-Attainers,

not liable to be reborn in any state of woe,

but assured of attaining to the Insight.

And so, Five-crest, of all,

even all those persons,

there is not one whose renunciation

is vain or barren;

in each case it will have brought fruit and development."

Thus spoke the Exalted One.

And Five-crest of the Gandharva fairies

was pleased at the word of the Exalted One,

and in delight and gladness

he saluted the Exalted One,

and with the salutation of the right side

he vanished from that place.

Here endeth the Story of the Lord High Steward.

[i1] This question has been fully discussed, and the reasons for the failure given, above, VoL I, pp. 105, 138 ff., and especially 141.

[i2] This difference in the mental endowments of the two gods, — the one the mere king of the gods, an Indian Zeus; and the other the Great First Cause, the outcome of the highest speculation — is always carefully observed in the various speeches ascribed, in the early Buddhist texts, to these divinities. See above, p. 175, for another instance.

[i3] The doctrinal material stands on a different footing. Already in 1877 I ventured to point out the difference (in 'Buddhism,' pp. 86-7), and the point has since increasingly forced itself upon my notice. Professor Windisch (in 'Die Composition des Mahāvastu' Leipzig, 1909, p. 494) supports this view.

[i4] Rhys Davids, J.R.A.S., 1898, 424.

[i5] There is a supplementary work, the Parivāra, much shorter, and consisting mainly of what we should now call examination papers. This volume, though most interesting from the point of view of the history of Indian education, presupposes the old Vinaya, and is later.

As is well known the Khandhakas come first in Oldenberg's edition, but the order in the MSS. is as above. See for instance Oldenberg's 'Catalogue of the Pāli MSS. in the India Office Library,' J.P.T.S., 1882, p. 59.

[i6] Compare Oldenberg's remarks on the Chinese translations of Vinaya at the end of his introduction to the Pāli Text.

[1] Pañcasikho Gandhabbo. See above, p. 244.

[2] Pavāraṇā.

[3] In Milinda, these contrasted distinctions are given to illustrate the exercise of sati ('minding' or 'remembering') by way of careful practice. 'Questions of King Milinda,' i. 58.

[4] Abhinippanno lābho.

[5] Ajjhāsayaṃ ādi-brahmacariyaṃ. Buddhaghosa says these two words are to be taken distributively, and refer to his lofty intentions and to the ethics of the Aryan Path.

[6] This sounds very much as if the Four Great Kings were looked upon as Recorders (in their memory, of course) of what had been said. They kept the minutes of the meeting. If so (the gods being made in the image of men) there must have been such Recorders at the meetings in the Mote Halls of the clans.

[7] §§ 5-12 repeated in the text. [Ed.: included in this version.]

[8] The Cy. here supplements: Himself desirous of clearing up this problem, it is as if he went on to say, that there was nothing wonderful in that, so he tells the story.

[9] It is evident from §§ 30, 31 that Govinda, literally 'Lord of the Herds,' was a title, not a name, and means Treasurer or Steward.

[10] Govindiye abhisiñcissāmi. Literally, 'I will anoint him to the Govinda-ship' (the Lordship over the herds). The expression 'anoint' is noteworthy. It suggests that the office was of royal rank. But a king was of lower rank then than now.

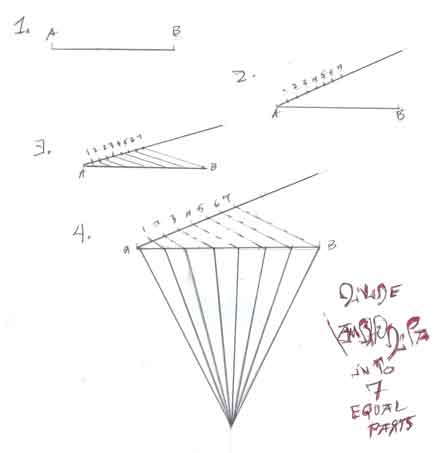

Sakaṭamukka. Cart-faced or fronted or mouthed. Apparently generally understood to be the shape of India, that is, wedge-shaped. This maybe from the shape of the Bullock's face, or from the narrowing of the cart at the front to the pole-yoke. See the map. Even just taking the Ganges Valley as 'the world' and squishing things around just a little one gets a triangle. So the translation might be: "So broad in the north and as narrow as the pole of a bullock cart at the south. So the question was how can a triangle be divided into 7? 'Central in the case of 7 pie-slices would be the fourth from either side.

First: this solves the problem only for a triangle of this shape. A solution to the question more compatable with the Dhamma would be:

To divide this Rose-Apple-Land into seven equal parts, place Mind (sati) in the center portion; on the right place Energy (viriya), Dhamma Research (Dhamma-Vicaya), and Enthusiasm (pīti); on the left place Impassivity (passadhi), Serenity (samādhi) and Detachment (upekkha).

![]() — p.p.

— p.p.

[11] Sakaṭamukka. This adjective, applied here to the earth, and at the end of the next section to the seven kingdoms, is at present quite unintelligible; and is left untranslated. The traditional explanations differ. Samarasekara (Colombo, 1905) translates here (p. 1016) dakuṇu pasin gael mukhayak lesaṭa, that is, 'on the south side like a waggon's mouth.' Buddhaghosa has nothing here; but below as applied to the kingdoms he explains 'with their mouths debouching together.' Neither is satisfactory. It has been suggested that it might mean 'facing the Wain,' that is, the constellation of the Great Bear. But this is unfortunately in the North. The front opening of a bullock waggon is (now) elliptical in form.

[12] If we follow the order of the names in this no doubt very old mnemonic doggerel, the result may be tabulated thus:

| City | Tribe | King |

| Dantapura | Kālingas | Sattabhu |