Oblog de, Oblog da, Life Goes On.

... except when it doesn't

What's New?

What's New?

![]()

2017

Sunday, December 31, 2017

Previous upload was Monday, November 27, 2017

Where everything is tottering

it is above all necessary that something, no matter what, remain steadfast

so that the lost can find a connection and the strayed a refuge.

— Metternich, quoted in Kissinger, World Order.

Buddhism: What the Buddha taught. Steadfast since 480 B.C.

With this upload a process of migrating the editorial content of the What's New? pages has begun. To this point, the contents of the 'What's New?' pages for 2017, 2016, 2015 and about half of 2014 have been integrated into the site at large with most materials being placed in the following pages/sections (Some editing has been done, more pages need to be edited for better organization, elimination of redundant expositions, consolidation of closely related topics.):

The short (and sometimes somewhat longer) descriptive paragraphs for individual suttas have been incorporated into the Sutta Index listings. Noted in detail below.

Longer discussions relating to the analysis of specific suttas are now located under the Dhammatalk Forum Heading: Dhammatalk, Sutta Vibangha: Sutta Analysis

Essays on various subjects have been added to their relevant subject categories on the Forum. Some have had new pages created, some were added to existing threads.

Short quotes from the suttas have been placed in the ever-popular 'One-Liners' section.

Inspiring quotes from outside the Dhamma have been placed under a new topic-head in the Dhammatalk Forum: Inspirational and (hopefully) Thought Provoking Quotations and Short Essays from Outside the Strictly Buddhist Literature.

Pajāpati

A Name for Māra

Pajāpati A name given to Māra, because he uses his power over all creatures.

—DPPN, Volume II, page 97

See MN 1 - Rhys Davids note 22

MA i.28, 33

MN 1 - Bhk. Bodhi note 10

Prajāpati, "lord of creation," is a name given by the Vedas to Indra, Agni, etc., as the highest of the Vedic divinities. But according to MA, Pajāpati here is a name for Māra because he is the ruler of this "generation" (pajā) made up of living beings.

The fact of Māra being called Pajāpati or Māra calling himself Pajāpati is not the essential thing to understand in the case of Pajāpati's Problem. The idea is that this god believes himself to be the Creator of the Created, and it is by the fact of being the Creator of the Created that he becomes the destroyer of the created, aka Death, the Evil One, Māra.

As a side issue Pajāpati is a popular name for women for the obvious reason that they are the Mothers of us all.

![]() [AN 11.9] Sandha Suttaṃ, Sandha, the Olds translation.

[AN 11.9] Sandha Suttaṃ, Sandha, the Olds translation.

This translation is obviously an experiment in an effort to find a word which fits the ancient understanding of the term jhāna. A higher order 'knowing' than our 'knowing'. 'Gnosis' fits well, both etymologically and in the sense that it is a knowing of a higher sort. It has the disadvantage of being long out of popular use. Bhk. Bodhi has opted for the popular understanding by using 'meditation'. The problem with that is that jhāna is not just the act of pondering in mind, but is also the state of seeing things without the interference of inferential thinking ... without, even, in one sense, mind itself.

This is not just 'perceiving, perceiving, perceiving' when it comes to fodder. It is because the mind of the ill-bred horse is occupied with the delights of his fodder, that he does not see that the food he is given comes with strings attached. The well-bred horse sees the whole situation as it is.

The second thing about this sutta, and it is the most important thing, is the explanation made by the Buddha of how it can be that the well-trained practitioner of jhāna can, in perceiving things, not have things as the object of his perception, and yet there is still perceiving.

To understand this, it is necessary to understand the nature of existence as it is dealt with in the Pāḷi (see DN 15 §22). It must be understood that there is, in the Pāḷi, consciousness, perception and experience that is not identified with, is not 'consciousness in contact with named form', and is therefor not considered to exist and that for a thing to be considered as existing it must be 'consciousness in contact with named form' or stated another way, 'identified-with consciousness', 'experience' versus 'sense-experience' and 'perception' versus 'sense-perception'. It is only then that we can see that what is being said here in this sutta is: "It is because he has destroyed his identified-with conscious perception and experience through the senses of earth, that there is, without earth as its direct object, perception of earth." There is experience of extra-sensory perception of earth without the idea 'I am perceiving earth.' This perception, consciousness, experience is free. It has freedom from identified-with perception, identified-with consciousness and sense-experience of existence as its object. That is its food. And not existing, not having become, not having a changeable thing as its object, it is not subject to change and ending.

As the plantain, bamboo, and the rush

Is each by the fruit it bears undone,

So the sinner is by men's homage slain,

As by her embryo the mule.

—SN 1.6.12, Mrs. Rhys Davids translation, slightly edited. It may be remembered at some future date the rash of famous men being accused of sexual harassment in the US at this time.

![]() Brief descriptions have been added to the sutta entries on the Index pages for Aṅguttara Nikāya, Navaka-Nipāta The Book of the Nines.

Brief descriptions have been added to the sutta entries on the Index pages for Aṅguttara Nikāya, Navaka-Nipāta The Book of the Nines.

Brief descriptions have been added to the sutta entries on the Index pages for Aṅguttara Nikāya, Dasaka-Nipāta The Book of the Tens.

Brief descriptions have been added to the sutta entries on the Index pages for Aṅguttara Nikāya, Eka-dasaka-Nipāta The Book of the Elevens.

Brief descriptions have been added to the sutta entries on the Index pages for

Saṃyutta Nikāya, 1: Sagāthā Vagga:

Saṃyutta 6 Brahmā Saṃyutta;

Saṃyutta 7 Brahmana Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 8 Vaṅgīsa-Thera Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 9 Vana Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 10 Yakkha Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 11 Sakka Saṃyutta.

No descriptions have been put in for SN 1. Saṃyuttas 1 through 5 because they are more or less reasonably described by their categorization in chapter and sutta title; further descriptions would be longer than the suttas themselves.

Brief descriptions have been added to the sutta entries on the Index pages for

Saṃyutta Nikāya, 2: Nidāna Vagga:

Saṃyutta 12 Nidāna Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 13 Abhisamaya Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 14 Dhatu Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 15 Anamattagga Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 16 Kassapa Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 17 Labha-Sakkara Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 18 Rāhula Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 19 Lakkhana Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 20 Opamma Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 21 Bhikkhu Saṃyutta.

Brief descriptions have been added to the sutta entries on the Index pages for

Saṃyutta Nikāya, 3: Khandha Vagga:

Saṃyutta 22 Khandha Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 23 Radha Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 24 Diṭṭhi Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 25 Okkantika Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 26 Uppada Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 27 Kilesa Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 28 Sāriputta Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 29 Nāga Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 30 Supaṇṇa Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 31 Gandhabbakāya Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 32 Valāha Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 33 Vacchagotta Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 34 Jhāna Saṃyutta.

Brief descriptions have been added to the sutta entries on the Index pages for

Saṃyutta Nikāya, 4: Saḷāyatana Vagga:

Saṃyutta 35 Saḷāyatana Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 36 Vedanā Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 37 Matugama Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 38 Jambhukhādaka Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 39 Samandāka Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 40 Moggallāna Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 41 Citta Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 42 Gāmani Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 43 Asaṅkhata Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 44 Avyākata Saṃyutta.

Brief descriptions have been added to the sutta entries on the Index pages for

Saṃyutta Nikāya, 5: Mahā Vagga:

Saṃyutta 45 Magga Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 46 Bojjhaṅga Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 47 Satipaṭṭhana Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 48 Indriya Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 49 Sammappadhāna Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 50 Bala Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 51 Iddhipāda Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 52 Anuruddha Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 53 Jhāna Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 54 Ānāpāna Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 55 Sotapatti Saṃyutta.

Saṃyutta 56 Sacca Saṃyutta.

To this point brief descriptions have been added to all the sutta entries on the Index pages for the Dīgha Nikāya, Majjhima Nikāya, Aṅguttara Nikāya and the Saṃutta Nikāya.

![]() [AN 9.43] Kāyasakkhi Suttaṃ, Bodily Realization, the Olds translation.

[AN 9.43] Kāyasakkhi Suttaṃ, Bodily Realization, the Olds translation.

Ānanda explains the extent of what the Buddha meant by the idea of 'bodily realization.' A seer-in-body is described as one who advances through the stages to arahantship in each case living in contact with the body.

[AN 9.44] Paññā-Vimutta Suttaṃ, Wisdom-Freed, the Olds translation.

Ānanda explains the extent of what the Buddha meant by the idea of being 'wisdom-freed.' One who is wisdom-freed has advanced through the stages to arahantship seeing the wisdom of each stage.

[AN 9.45] Paññā-Vimutta Suttaṃ, By Two-Measures Freed, the Olds translation.

Ānanda explains the extent of what the Buddha meant by the idea of being 'by two-measures freed.' Such a one is both a seer-in-body and wisdom-freed. A seer-in-body is described as one who advances through the stages to arahantship in each case living in contact with the body. One who is wisdom-freed has advanced through the stages to arahantship seeing the wisdom of each stage.

Monday, November 27, 2017

Previous upload was Tuesday, October, 24, 2017

Controlling the Bent of Ones Heart

Following upon the attainment of seven

one controls the bent of his heart,

is not controlled by the bent of his heart.

What are the seven?

Here one has skill in serenity:

he has skill in attaining serenity;

he has skill in maintaining serenity;

he has skill in rousing up serenity;

he has skill in managing serenity;

he has skill in the pastures of serenity;

he has skill in abandoning serenity.

■

This translation departs from the conventional rendering of the factors said to be involved in the management of samādhi.

The term 'samādhi' itself is most frequently translated 'concentration. Here it is rendered 'serenity';

the term 'vuṭṭhānakusalo' always rendered 'skill in emergence', is here rendered 'skill in rousing up';

the term 'kallitakusalo', Bhk. Bodhi: 'fitness'; Hare: 'well-being', is here rendered 'skill in managing';

and the term 'abhinīhārakusalo' Bhk. Bodhi: 'skilled in resolution regarding' Hare: 'skilled in applying', is here rendered 'sill in abandoning'

I justify these radical departures from convention as follows:

The first consideration is the construction of the sutta. Both Hare and Bhk. Bodhi set the list up as seven different factors for controlling the heart. I have set the list up in the form of Summary: Six Factors. This, of course, creates problems as to why this should be included among the Sevens, but where one can justify 'Summary:Factors' as being composed of seven items; one has difficulty justifying what is in the first item a summary as a discrete factor among six others.

This construction is supported by the syntax of the follow-up repetition describing Sariputta's skills in this area.

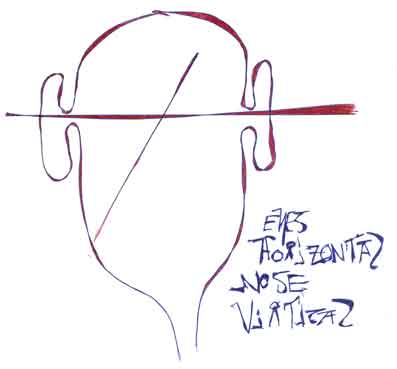

Why is it that 'samādhi' should not be rendered 'concentration'? It comes down to the fact that concentration is too limited in scope for what is covered by the idea of 'samādhi'. 'Samādhi' encompasses the entire practice of Buddhism from Generosity on up to the point of attaining 'upekkha' (detachment). 'Samādhi,' where the aspect of it applies to the cultivation of such a high degree of calm oversight that the jhānas are attained, contains the idea of concentration, but there only as one of a number of factors that must be cultivated. Further, 'samādhi' etymologically means 'even-over' an even-minded over-seeing, not a bearing down on a single thing to the exclusion of all else: the very description of the factors within the jhānas, for example, excludes the idea of a focus on a single thing. Finally, experience will show the meditator that concentration, made the exclusive practice rather than a tool is impossible to manage. The idea, where it is useful, is rather 'focus' than 'concentration'. Attempting to concentrate on the point where the breath enters and emerges from the nose, for example is the attempt to pin down a thing that is continuously changing and trying to keep it from changing in order to practice according to this method will lead to going way off track in ways that are impossible to describe as anything but a very unhappy state of madness and that liberation, when it is actually experienced in practice is precisely an even-minded over-seeing of whatever its subject may be. This is a state frequently attained and described by artists, musicians, writers and properly oriented meditators.

The next consideration is to ask why anyone would wish to emerge from serenity (we will deal with letting it go below). Here the idea of 'samādhi', because it is being translated as 'concentration' and concentration is being conflated with jhāna practice, translators have relied for what they do not experience on the exposition of the commentator. The translation I have used is both supported by the PED and by common sense.

'Kallitakusalo'. Bhk. Bodhi does not explain what he means by 'fitness for concentration', that is whether he is speaking of the fitness of the meditator or the fitness of his subject of meditation or the fitness of something else. Hare wants it to be the pleasantness of the concentration. This factor must be within the control of the meditator. This is a sutta which is describing factors to be managed by the meditator so as to render his heart controllable. He must be able to influence the situation. "Management". Again this meaning is supported by PED.

'Abhinīhārakusalo.' Here Hare apologizes in a footnote for a rendering in a previous translation of this term as 'resolve' where his understanding was the use of a mental command such as 'let this session last one hour,' or 'let no damage by earth, water, fire, or wind occur to my abode during this session'. He then, following commentary, adopts the term 'skill in applying', meaning 'skill in attaining the jhānas ' Bhk. Bodhi, not mentioning what he follows, renders the term "skilled in resolution." It is tempting to break ones serenity by ridicule here, but I will manage my serenity, not emerging from my serenity, and simply ask the reader to understand that serenity is not the final goal in this system. It is a stepping-stone to detachment (upekkha) which is itself a stepping stone to freedom and knowledge of freedom in freedom, and therefore must be let go of, pleasant abiding though it may be.

For a sutta to be a lesson in True Dhamma, it should always point in the direction of the final goal. Such is the intent of this translation.

—From the Introduction to the Olds translation of AN 7.38.

![]() [AN 4.133] Neyya Puggala Suttaṃ, Led to Comprehension, the Olds translation.

[AN 4.133] Neyya Puggala Suttaṃ, Led to Comprehension, the Olds translation.

[AN 4.140] Vādī Suttaṃ, Professors, the Olds translation.

[AN 7.38] Citta-Vasavattana Suttaṃ, Controlling the Bent of Ones Heart, the Olds translation.

[AN 9.9] Puggala Suttaṃ, Men, the Olds translation.

The Buddha lists the nine stages from commoner to Arahant.

Four Types of Persons Found in This World

One who comprehends intuitively;

one who comprehends upon analysis;

one who comprehends after being instructed;

one who comprehends only the letter.

—[AN 4.133] Neyya Puggala Suttaṃ, Olds trans.

The first inderstands the full scope of the statement: "This is Pain" immediately upon hearing it.

The second understands the full scope of the statement: "This is Pain" upon figuring out that the scope of the term 'this' includes form, sense-experience, perception, own-making, and consciousness.

The third understands the full scope of the statement: "This is Pain" upon being instructed again and again that the scope of the term 'this' includes form, sense-experience, perception, own-making, and consciousness, and that this group of terms encompasses all that which is understood to be a living, existing being, and that birth, aging, sickness and death, grief and lamentation, pain and misery and despair; not getting what is wished-for; getting what is not wished-for; in a word, that the entire stockpile of temptations (form, sense-experience, perception, own-making, and consciousness) is a heap of flaming du-k-kha.

The fourth type is able only to repeat that in the Buddhism that is taught on this site, what is taught is that "This is pain" and that the scope of the term 'this' is said to include form, sense-experience, perception, own-making, and consciousness, and that this group of terms encompasses all that which is understood to be a living, existing being, and that birth, aging, sickness and death, grief and lamentation, pain and misery and despair; not getting what is wished-for; getting what is not wished-for; in a word, that the entire stockpile of temptations (form, sense-experience, perception, own-making, and consciousness) is a heap of flaming du-k-kha.

Four Types of Professors Found in This World

The Professor who is baffled by the sense

not the letter.

The Professor who is baffled by the letter,

not the sense.

The Professor who is baffled by both the sense

and the letter.

The Professor who is baffled by neither the sense

nor the letter.

It is, however, impossible, there is no probability,

that the Professor, who is possessed of the four analytical powers (having knowledge of sense; knowledge of things; knowledge of etymology; and having his wits about him),

could be baffled by both the sense and the letter."

—[AN 4.140] Vādī Suttaṃ, Olds trans.

![]() — p.p.

— p.p.

![]() Brief descriptions have been added to the sutta entries on the Index pages for the Majjhima Nikāya, The Middle-Length Discourses.

Brief descriptions have been added to the sutta entries on the Index pages for the Majjhima Nikāya, The Middle-Length Discourses.

Brief descriptions have been added to the sutta entries on the Index pages for the Dīgha Nikāya, The Long Discourses.

Brief descriptions have been added to the sutta entries on the Index pages for Aṅguttara Nikāya, Tika-Nipāta The Book of the Threes.

No descriptions have been added for the Ones and Twos as the descriptions would end up being longer than the suttas themselves. Chapter titles give sufficient information as to the subject covered.

Brief descriptions have been added to the sutta entries on the Index pages for Aṅguttara Nikāya, Catukkanipata-Nipāta, The Book of the Fours.

Brief descriptions have been added to the sutta entries on the Index pages for Aṅguttara Nikāya, Pancakanipata-Nipāta, The Book of the Fives.

Brief descriptions have been added to the sutta entries on the Index pages for Aṅguttara Nikāya, Chakkanipata-Nipāta, The Book of the Sixes.

Brief descriptions have been added to the sutta entries on the Index pages for Aṅguttara Nikāya, Sattaka-Nipāta, The Book of the Sevens.

Brief descriptions have been added to the sutta entries on the Index pages for Aṅguttara Nikāya, Atthaka-Nipāta, The Book of the Eights.

![]() [MN 19] Dvedhā-Vitakka Suttaṃ, Two Kinds of Thoughts, the Venerable M. Punnaji translation.

[MN 19] Dvedhā-Vitakka Suttaṃ, Two Kinds of Thoughts, the Venerable M. Punnaji translation.

The Buddha describes a method for categorizing thought which makes it less difficult to supress disadvantageous thoughts, still advantageous thoughts and attain tranquillity of mind.

[MN 20] Vitakka-Saṇṭhāna Suttaṃ, Technique of Calming Thoughts, the Venerable M. Punnaji translation.

The Buddha describes five stands the seeker after higher states of mind can adopt in his effort to eliminate unwanted, degenerate, debilitating thoughts.

[MN 107] Gaṇaka-Moggallāna Suttaṃ, Gaṇaka-Moggallāna, the Venerable M. Punnaji translation.

The Buddha teaches a brahman his Gradual Course of instruction and answers his question as to why some attain Nibbāna this way and why some do not.

[MN 125] Danta-Bhūmi Suttaṃ, The Grade of the Tamed, the Venerable M. Punnaji translation.

The Buddha describes the course of training for a bhikkhu.

The Anatta-me Lesson

It is vital to an understanding of Dhamma, to the escape from kamma, to the attainment of freedom, to the attainment of detachment that this be clearly understood:

It is not:

"There is no self,"

it is:

"This is not the self," or "All Things are Not-Self," or "There is no thing there that is the self."

The statement: "There is no self," is a diṭṭhi, a point of view, an opinion, a theory, an hypothesis, a deduction, a baseless conclusion, unprovable, wrong, and a thing which prevents attaining escape from kamma, the attainment of freedom, the attainment of detachment. It is a statement that is not made by the Buddha and is against true Dhamma.

It is a point of view, or opinion because it is one among several ways of seeing the phenomena of individuality.

It is a theory or hypothesis because it postulates an unproven position.

It is a deduction or conclusion made from the statement "sabba Dhamma anatta". But to say "There is no self" is not a conclusion that can be drawn from the statement 'all things are not the self' (suppose there were a self that was not a 'thing'? And in fact the definition of existence in the Buddha's Dhamma, the definition of a 'thing' which has become a 'thing', a dhamma, is not that which is commonly understood as the meaning of existence. In this system 'existence' means the living of a living being that has come into existence through own-making or con-struction by an individual and consists of named-form plus consciousness [DN 15]— being some sort of identified being in some sort of world of beings — such a definition allows for consciousness outside of existence, just not individually identified-with consciousness); it is not the same thing as to say "there is no self." The latter is an absolute statement. For it to be stated truthfully by someone, that person would need to be able to see all things at all times, past, future and present. Even the Buddhas do not claim such vision.

It is unprovable because it is impossible for anyone to say such a thing is true from personal knowledge.

It is wrong because there are opposing opinions and points of view on the matter. From those points of view it is wrong.

For him who sees the coming into existence of things there can be no holding of the opinion: "There is not";

For him who sees the passing out of existence of things there can be no holding of the opinion "There is."

It is a thing which prevents attainment of escape from kamma, attainment of freedom and detachment because an individual who holds the belief that there is no self has no incentive to improve himself or escape kamma or existence in this world. In this visible world his philosophy is "Eat, drink and make merry, for tomorrow we die!" or "We're not here for a long time, we're here for a good time," or "We only have one life, so make the most of it," and thus he is bound to kamma. At the break-up of the body at death he will be unable to adhere to his position that there is no self and will identify, as he has habitually done, (as he would see if he had any reasonable degree of knowledge of himself) with the disintegrating elements and follow them into rebirth.

It is a point of view condemned in the Dhamma as being the annihilationist view.

On the other hand, to say "This", or "'All Things' are not the self" is to point to something that can be seen for himself by anyone who looks at the matter understanding the criteria defining the idea of self in the Buddha's system: That it is something that is under one's control; that it is without change (in the sense that it is always "me" and "mine"); that it is without pain, ending and subject to rebirth in accordance with kamma. The individual can see of himself how it is out of his control, changes and is painful and he can determine that all things that have come into existence are by definition of the same nature.

Here's the thing. Understanding this not-self idea clearly is not enough, neither is understanding and seeing the logic, neither is understanding and seeing the logic and believing that it is the correct way to see things. What is needed is to be able to see that This is not the self is a fact. You need to be able to look down there or out there and see the body or whatever it is you have previously felt was the you of you and see it as a separate entity. Not you. A thing that is not your self out there. It is only then that it can be let go. It cannot be done sitting there 'seeing' no self. You can't see no self. How can you then let it go?

Here's the other thing that is important: If you do not have this idea clearly in your mind, you have not yet broken the sakāyadiṭṭhi and breaking the sakāyadiṭṭhi is one of the three things you must do in order to be able to call yourself a Streamwinner and being a Streamwinner is necessary to assure yourself that rebirth in Hell, as a Ghost or daemon or animal is no longer a possibility for you.

Otherwise you may be a Streamwinner by faith, but if you die in that state there is this much that must be done by you before you move on in the next life. Now is the Time!

Be careful! Do not let yourself carelessly state this matter or by reading without paying attention accepting the incorrect statement as made by others.

See especially: [AN 6.38] Self-doer, Olds trans, introductiona and translation.

Authenticity

'The doctrines, Upali, of which you may know: "These doctrines lead one not to complete weariness of the world, nor to dispassion, nor to ending, nor to calm, nor to knowledge, nor to the awakening, nor to the cool" — regard them definitely as not Dhamma, not the discipline, not the word of the Teacher. But the doctrines of which you may know: "These doctrines lead one to complete weariness, dispassion, ending, calm, knowledge, the awakening, the cool" — regard them unreservedly as Dhamma, the discipline, the word of the Teacher.'

—AN 7.79 Hare translation

A thing that is both misleading and stripping the Dhamma of all its magic by directing people's attention to fault finding is the question of authenticity.

Because a sutta which appears in one place is made up from ideas found individually in other places does not make either the one or the other inauthentic. It is the effectiveness of the idea in promoting freedom from pain and detachment from existence that determines its authenticity.

It is not because a certain idea found in the Suttas was spoken by a disciple and not the Buddha that that idea is inauthentic. It is the effectiveness of the idea in promoting freedom from pain and detachment from existence that determines its authenticity.

It is not even that an idea found completely outside of the Dhamma is necessarily inauthentic. If that idea is effective in promoting freedom from pain and detachment from existence in both its wording and spirit, then that statement is Dhamma; is to that extent the product of an awakened mind.

The idea of determining authenticity by comparison of sutta with sutta was never intended as a substitute for putting the teaching into practice. The truth of an idea, or its effectiveness is not proven by its agreement with ideas found in other places in the Dhamma. Such a test of authenticity is useful only where there is an outright contradiction in terminology that cannot be resolved through practice. Such a test of authenticity is found to be useful to the very beginner who is confused by conflicting statements made by commentaries, summaries, interpretations, translations and discussions and the suttas. Comparison of what is stated in a commentary with what is stated in the suttas; or what is stated as being stated in the suttas with what is actually to be found in the suttas is a valuable tool in this case. It should not be being used to whittle away at the suttas through ignorant fault-finding — pointing out contradictions which are simply changes in wording or context or (the majority) differences in translations.

But in more than 50 years of Dhamma study I have yet to find or hear of a question of authenticity based on an apparent contradiction in the Suttas that did not prove to be in stead a paradox that required only that it be resolved by an elevation of perspective.

Again, it is not because a certain sutta contains phrases that are older than another sutta that makes the one authentic and the other inauthentic. The suttas were collected from the very first and the four official collections were an early aspect of the life of the bhikkhus and were in the charge of the highest level of Gotama's followers. Over the period of their collection (which spanned from the beginning of Gotama's teaching to well beyond his death) suttas were added when they were found or remembered. Early and late were intermixed early and late as was dictated by the various organizations of the baskets. The four baskets were made so as to be redundant within themselves and across the Nikāyas in different, independent ways. When a new sutta was added it, or its ideas were incorporated into each of the four Nikāyas in different ways. This was a matter of preserving the ideas in the Dhamma.

It is not a proof of inauthenticity that a sutta is missing or present in the Pāḷi when it is present or absent in the Chinese or Sanskrit or Tibetan or in one collection or another or the reverse.

It is not a proof of inauthenticity that a sutta or a part of a sutta is in one order in one collection and in another order in another collection.

It is the effectiveness of the idea in promoting freedom from pain and detachment from existence that determines its authenticity. That is the only criteria that is useful and not a waste of time.

Further, the idea that what we have in the Pāḷi is not the language of the Buddha is absurd. It should be dismissed by any rational thinking mind. For that to be the case the whole of the Dhamma as we have it would have required translation from Gotama's spoken language into the Pāḷi and that from the very first and by a continuous coherent body of translators as wide-awake as the Buddha himself and not by the various groups and individuals to whom we know the suttas were actually delivered. We can see the mess that has been made of the effort to translate the Pāḷi into English, which is for the modern translator conveniently in written form with its consistent terminology and ideas already worked out for him. It took more than a hundred years just to complete the four Nikāyas and there is still no translation which has a consistent vocabulary (and therefore construction of a consistent Dhamma) across the entire four nikayas. As mentioned previously, memorization began during the lifetime of the Buddha; is it being said that the translation too began during his lifetime? If so or if not, at what point, and by whom, and how is it that such a monstruous project is nowhere mentioned? And how is it that the Four Nikāyas maintain such consistency? It is preposterous; it is beyond reasonable to maintain this idea. There may have been editing and errors around the edges, but the Dhamma within is consistent and employs massive redundancy which acts to scour out wrong doctrine; such consistency could only have been maintained by an awakened Buddha or Arahant and the arahant would never alter word or spirit of the Teacher or have had any reason to translate it from one vernacular to another.

The idea that the language of the Buddha was different than the Pāḷi is suggested by the theory that the Pāḷi came after the Vedic and Sanskrit and that traces of supposedly older prakrits, or spoken languages are found here and there in the Pāḷi. Leaving open the idea that language begins perfect and complex and deteriorates into common language defies reason, there is no reason to think that what we have in the Pāḷi is not an artificial language in the sense that of the terms in common use in the Time of Gotama, Gotama selected those which most concretely expressed his ideas and that among those were some of the oldest terms known as well as some that were more modern, and that, just to be safe, they were all defined internally. We could, and translators of the Pāḷi really should, do the same thing with English.

It is the nature of the Pāḷi that it is so constructed as to be comprehensible across Time, Culture and state of consciousness such that it is possible to translate it in a great vareity of ways that are more or less completely consistent across its entirety and which cannot but be called true or correct translations but which will produce as a result a Dhamma which is strictly limited to a certain strata of reader.

Such is the case, for example, in the translation of 'dukkha' as 'stress'. It is possible for the well-educated American-English speaker to understand this term as applicable to aging, sickness and death; grief and lamentation; pain and misery; and despair. It is also subject to being misunderstood by those who do not both understand the aim of the Dhamma and the scope of the intended use of this term. One result is an industry riding on the authority of the Buddha that makes money from teaching businesses how to reduce stress in their employees. Another is a class of Buddhists that view the scope of the Dhamma in strictly worldly terms; as a practice aimed strictly or predominantly at bringing one success and happiness in this world. There are similar objections to the use of 'anxiety' 'angst' and even 'suffering' (the lower classes do not admit they suffer). 'Pain' works across Time and State of consciousness for English speakers. The gods would have a hard time understanding the term. 'Shit' is understood across Time, Culture, and State of Consciousness and can be pointed to where even the very clear connotation and near universal meaning of the sounds do not come across clearly.

Authenticity in this sense can only be claimed by the original Pāḷi. Do not make the mistake that is found throughout the web of arguing a point based on translation or worse of confusing the terms of one translation with those of another. Again: there is no set of translations out there today that is consistent in its terminology across the whole of the suttas.

You need to understand why you are interested in becoming a Buddhist. If you are simply seeking a rudder to keep you on a steady ethical course in the madness of this world, you have found a good rudder, but do not mistake your satisfaction at the rationality of the Dhamma in this area for the full scope of its purpose. Similarly you may be seeking success in this world through skillful manipulation of kamma. Again you will find a consummate guide in the Dhamma for that purpose, but again, do not mistake that success for the purpose of the Dhamma. The Dhamma was intended, over and above all as a method for escaping kamma, escaping the endless cycle of rebirth. To achieve this end you need to understand that this study needs to become your primary interest in life and that it is, baring the fact that you are some sort of genius or have arrived here in some advanced state because of hard work done in a previous life, going to take you the rest of your life to get to any degree of accomplishment in the system and it will be the hardest task you have ever put yourself through. Then you may understand:

Beggars! The best course does not have a gains-honour-reputation-core,

nor an accomplishment-in-ethics-core,

nor a accomplishment-in-serenity-core,

nor a knowledge-vision-core.

But there is beggars, unshakable heart-release —

here, beggars the best course is for attainment of this.

This is its hardwood.

This is its encompassing end.

Desire and Temptation

Taṇhā and Upādāna

[Wolf Larsen] "... 'as I see it, a man does things because of desire. He has many desires. He may desire to escape pain, or to enjoy pleasure. But whatever he does, he does because he desires to do it.'

[Mr. Van Weyden] "'... temptation is temptation whether the man yield or overcome. Fire is fanned by the wind until it leaps up fiercely. So is desire like fire. It is fanned, as by a wind, by sight of the thing desired, or by a new and luring description or comprehension of the thing desired. There lies the temptation. It is the wind that fans the desire until it leaps up to mastery. That's temptation. It may not fan sufficiently to make the desire overmastering, but in so far as it fans at all, that far is it temptation. And ... it may tempt for good as well as for evil.'"

The Sea Wolf by Jack London, First published in book form by The Macmillan Co., New York, in 1904. A book that should be read as an exercise in the cultivation of ethical thinking.

Extension: Understanding that this is not a literal translation, just a useful one: Upādāna-K-khandhā = Storehouses of Temptation = the Chinese idea of the Warehouse-Consciousness. Piles of stuff which fan the flames of becoming when dwelt on without caution. Forms, Sensations and sense experiences; perceptions, own-makings or 'things to do'; states of consciousness.

This is a very useful piece of information to have when reflecting on your meditation practice. What it means is that when you are sitting there with your mind focused on the mouth and the breathing, you are in effect "not-engaging" with temptations. This is the practice for 'samādhi' (serenity; being 'even-over'; blissfully above it all) in its highest form. It is not the same as, in fact it is the mirror opposite of the practice as found in [DN 22] the Satipatthāna Sutta where the practice of minding the mouth and the breathing is directed at observing the origination, existence and passing away of things.

What has happened then, in practice, is that properly exercised, the Satipaṭṭhana sutta will bring one to the perception that there is no thing there that does not change, bring pain and is only mistakenly taken for the self. The next logical step is to let go of 'things' and this is the practice for accomplishing that end.

Misunderstood, satipatthāna practice is being described as a concentration on the breathing, and is further being confused in the same way with samādhi practice, but even a casual reading without the blinders imposed by authorities will show you that the idea is not paying attention to the breathing in-and-of itself, it is understanding the breathing and all sorts of other phenomena encompassed under the headings of body, sense experience, mental states and the Dhamma, in terms of their origin, existence and passing away. Concentrated focus on the breathing as an end in itself, will result in going completely wacka-ding-hoy. Using the same focus on the mouth and the breathing when it is not the object in-and-of itself, but a tool for rising above all else does not lead to madness and does lead to serenity.

Summary: Satipatthāna practice begins with minding the breathing and there minding the breathing is intended to be a take-off point for analyzing body, sense experience, mental states and the Dhamma.

When insight into the nature of body, sense experience, mental states and the Dhamma has shown one that there is no thing there that does not change, bring pain and is the self, the practice moves on to the cultivation of serenity by way of using focus on the mouth and the breathing as a tool for rising above that which fans the fuel of becoming (temptations): desire for forms, sensations, perceptions, doing things, and consciousness itself.

One more time: When minding the breathing is focused outward it is Satipaṭṭhana Practice; when it is used to rise above outward focus it is Samādhi practice.

Tuesday, October, 24, 2017

Previous upload was Tuesday, September 26, 2017

The Pāḷi Text Society announces the publication of a new book:

The Suttanipata: An Ancient Collection of the Buddha's Discourses Together with its Commentaries, tr. Bhikkhu Bodhi. [Published under agreement with Wisdom Publications]

ISBN-10 0 86013 516 0

ISBN-13 978 0 86013 516 6

List price: £ 50.00

This volume offers a new translation of the Suttanipata together with its commentarial apparatus. It is an anthology of discourses ascribed to the Buddha, included in the Khuddaka Nikāya, the fifth collection in the Sutta Pitaka of the Pāḷi Canon. Most of the discourses in the Suttanipata are in verse, some in mixed prose and verse. Several occur elsewhere in the Sutta Pitaka, but most are unique to this collection. The commentary, the Paramatthajotika II, already recognizes its composite nature when, in its introductory verses, it says that "it is so designated because it was recited by compiling suitable suttas from here and there." Exactly when the anthology came into existence is not known, but since, as a collection it has no parallel in the texts surviving from other Early Buddhist schools, it is likely to be unique to the Pāḷi school now known as Theravada.

![]() [SN 5.48.40] Uppatika Suttaṃ In Order Experienced, the M. Olds translation.

[SN 5.48.40] Uppatika Suttaṃ In Order Experienced, the M. Olds translation.

Linked to the Pāḷi and the Woodward translation.

The Buddha explains how each of the five forces (that of pleasure, that of pain, that of mental ease, that of mental discomfort and that of detachment) is to be understood in its arising, in its settling down and in the escape from it.

There is some discussion of this sutta centering on the question: How is it that this sutta speaks of ending domanassa in the second jhāna, when unwholesome states are spoken of as being gotten rid of to attain the first jhana?

The very first thing to understand here is that 'dukkha' or 'domanassa' or any of the other terms mentioned here are not the same things as 'Dukkh'indriyam', etc. The sutta is not speaking about 'dukkha', etc., it is speaking about 'dukkha-indriya' 'dukkha's force' or 'the force of dukkha'.

The second thing to understand is that the translation of 'indriya' as 'sense organ' or 'faculty' breaks down here. The Indriya are 'forces'; energy fields. How is 'dukkha' (pain) in any way a sense organ or faculty?

The next thing to understand is that neither pain nor the force of pain (or any of the other forces and their sources) are in-and-of-themselves unwholesome states. It is the personal reaction to the force that is the unwholesome state. The force can exist or appear to one without it being allowed to become an unwholesome state.

Again, to understand that this is not a corrupt sutta it must be understood that the Forces are not things in-and-of themselves. They are terms describing the potential of things which arise during jhāna (or elsewhere) to disrupt the jhāna or other aspects of one's practice.

'Force' describes the ability of a thing to affect one. Like 'horse-power'. The force of a hurricane (1,2,3,4) is not the wind or rain, it is the power of the wind or rain to cause damage. The force of an earthquake (5, 6, 7) is a measure of its ability to cause damage. It is not the actual shaking of the earth.

So the force of dukkha is not pain itself, but its potential to cause one to become upset, want to get away from it, or for it to otherwise disrupt one's ability to achieve freedom from pain. Rebirth has enormous potential to cause disturbance. Physical pain much less so.

These forces can enter your practice at any stage. You have been sitting in the first jhāna, above unskillful states, for the past three hours and that pain in the ass that arises after such a time from the impression made there from the seam in your pants threatens to cause you to get up and do something else. Recognizing in the force of pain, its ability to disturb your sitting practice, knowing how it arises (from wanting to get rid of the pain itself), knowing how it ends (by ending the wanting), one has recognized and understood the force.

The work of entering the various jhāna, the factors involved in attaining the jhanas, progressively eliminates the various forces as described in the sutta.

Though the pain may endure, it does not disturb.

The force of pain is to be got rid of in the first jhana; pain itself may not be got rid of before the fourth jhāna, the unskillful state of being disturbed by the force is got rid of prior to the first jhāna.

The force of misery (domanassa) is to be eliminated by the process of entering the second jhāna, domanassa itself may not be eliminated before achieving the third jhāna in the process of entering the fourth jhāna, the unskillful state of being disturbed by the force is to be got rid of prior to the first jhāna.

And it is the same with the other forces.

There are a number of other things we can learn from this sutta. The first is that we do not, as teachers of the Dhamma, need always to stick ridigidly to the precise order of the various lists of elements of the Dhamma. Here, for example, the usual order of this group of five Forces has been modified by Gotama so as to render it more in line with the experience and needs of the meditator. I suggest that the teacher who has a firm grip on his understanding of Dhamma should regard its various elements as tinker toys or pieces in an erector set, to be formed into a lesson as would best suit the student being instructed. Another thing that can be taken from this sutta is the understanding by the translator that not only do the various Pāḷi Dictionaries represent translations, so that the definitions given in them and are suspect in themselves, but that the so-called 'original' Pāḷi itself is a product of an editing that must have followed a translation of sorts for its breaking up into words and sentenses (the earliest written documents ran-in all the words without breaks) and is also, therefore, subject to revision. A third thing we can learn is, when paying close attention to both translation and the Pāḷi, the methodology of the translator can be seen. Difficulties are passed over, terminologies and phrasings from previous translations are adopted without careful consideration. Translations are derived from inference and logical reasoning where understanding through experience could be the only way a true meaning could be known. Etymologies which could go both forward and backward are taken to go in one direction only. And some things can now never be known with absolute certainty (for example the jhanas) because the only absolutely reliable authority (the Buddha, or one who learned directly from him) is long gone. I'm just saying! The Buddha tells us to beware of reliance on authority.

Exercise: Take this sutta and substitute the other 'authoritative' translations for the term 'Indriya' and think through the way these differences would change the entire practice:

Hare, Woodward: Controlling faculties, controlling powers,

Bhk. Bodhi, Rhys Davids, Bhk. Thanissaro, Walshe, Woodward: faculties.

Bhk. Thanissaro has an entire meditation course mapped out using 'faculties' as a translation for "Indriya"!

"... it is a curious fact, that the more ignorant and degraded men are, the more contemptuously they look upon those whom they deem their inferiors."

■

"In the days of Paganism, it [the regal office in Tahiti] was supported by all the power of a numerous priesthood, and was solemnly connected with the entire superstitious idolatry of the land. The monarch claimed to be a sort of bye-blow of Tararroa, the Saturn of the Polynesian mythology, and cousin-german to inferior deities. His person was thrice holy; if he entered an ordinary dwelling, never mind for how short a time, it was demolished when he left; no common mortal being thought worthy to inhabit it afterward.

'I'm a greater man than King George,' said the incorrigible young Otoo to the first missionaries; 'he rides on a horse, and I on a man.' Such was the case. He travelled post through his dominions on the shoulders of his subjects; and relays of mortal beings were provided in all the valleys.

But alas! how times have changed; how transient human greatness. Some years since, Pomaree Vahinee I, the granddaughter of the proud Otoo, went into the laundry business; publicly soliciting, by her agents, the washing of the linen belonging to the officers of ships touching in her harbours."

- Herman Melville, Omoo, 1847

"Speech, originally, was the device whereby Man learned, imperfectly, to transmit the thoughts and emotions of his mind. By setting up arbitrary sounds and combinations of sounds to represent certain mental nuances, he developed a method of communication - but one which in its clumsiness and thick-thumbed inadequacy degenerated all the delicacy of the mind into gross and guttural signaling.

Down - down - the results can be followed: and all the suffering that humanity ever knew can be traced to the one fact that no man in the history of the Galaxy, until Hari Seldon, and very few men thereafter, could really understand one another. Every human being lived behind an impenetrable wall of choking mist within which no other but he existed. Occasionally there were the dim signals from deep within the cavern in which another man was located - so that each might grope towards the other. Yet because they did not know one another, and could not understand one another, and dared not trust one another, and felt from infancy the terrors and insecurity of that ultimate isolation - there was the hunted fear of man for man, the savage rapacity of man toward man.

-Second Foundation, Vol. 3 of the Foundation Trillogy, by Isaac Asimov, Everyman's Library, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2010, pg. 493

We must object to the statement that no man has ever understood his fellow men, and to the one that suggests that Hari Seldon, standing in for Isaac Asimov, did, at least in so far as it is demonstrated in this book. What is the case is that very few have ever learned how to understand their fellow men from those that did understand and taught the way to do so in a way that could have been understood by them.

Tuesday, September 26, 2017

Previous upload was Saturday, August 12, 2017

![]() [AN 5.106] Aṅguttara Nikāya, The Book of the Fives, #106, Comfortably Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation.

[AN 5.106] Aṅguttara Nikāya, The Book of the Fives, #106, Comfortably Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation.

Linked to the Pāḷi and the Hare translations.

Ānanda asks about living comfortably as a bhikkhu. The Buddha gives him five ways which are also stages on the way.

[AN 10.99] Aṅguttara Nikāya, The Book of the Tens, #99, To Upāḷi Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation.

Upali asks leave to become a forest-dwelling bhikkhu. The Buddha, discourages him with a long discourse on what actually needs to be accomplished in this system to achieve the goal and how difficult it is to do that as a forest bhikkhu with no skill at serenity.

[MN 21] Majjhima Nikāya, #21: The Simile of the Saw, Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation, unabridged from what was previously only an excerpt.

Linked to the Chalmers, Horner, Nanamoli/Bodhi, and Upalavana translations.

A famous sutta dealing with the idea that the student of this system should not concern himself with worldly matters, even those so close to home as the abuse of nuns; also dealing with the need for patience and endurance when faced with abusive speech ... to be counteracted by training in a heart of friendliness towards one and all.

Bhikkhu Thanissaro Posts New Essay

A new essay by Bhikkhu Thanissaro addresses some timely issues. Worth a read.

Love Your Anxiety

"The flood of anxiety is not the end for man. It is, rather, a "school" that provides man with the ultimate education, the final maturity. It is a better teacher than reality, says Kierkegaard, because reality can be lied about, twisted, and tamed by the tricks of cultural perception and repression. But anxiety cannot be lied about. Once you face up to it, it reveals the truth of your situation; and only by seeing that truth can you open a new possibility for yourself.

'He who is educated by dread [anxiety] is educated by possibility. ... When such a person, therefore, goes out from the school of possibility, and knows more thoroughly than a child knows the alphabet that he demands of life absolutely nothing, and that terror, perdition, annihilation, dwell next door to every man, and has learned the profitable lesson that every dread which alarms may the next instant become a fact, he will then interpret reality differently. ...'"

The Denial of Death, Ernest Becker, Free Press Paperbacks, Published by Simon & Schuster, New York 1973 discussing Kierkegaard, The Concept of Dread, 1844, Princeton: University Press edition, 1957, translated by Walter Lowrie.

I cannot recommend this book, (nor Kierkegaard's either). On page 90 he concludes that dropping the programmed personality and facing the terror of the loneliness of a life bound up in chaos can only avoid madness through the individual placing faith that an Ultimate Creator God has some reasonable design in back of it all.

At this point the Buddhist educated mind just shuts down.

Facing 'the terror', is of course Pajapati's problem, but what Becker and Kierkegaard fail to see is that this faith is just another sort of social conditioning the results of which are as stale, unsatisfactory and impermanent as any other and that there is another solution, namely the abandoning of any idea of self there. By realizing through examination at the time of perception of the chaos of the world that there is nothing in that that is the self, one actually experiences the dropping off of attachment to this world and by that the subjective experience of terror that results from being helpless within it.

Virtual Reality

"There is something extraordinary that you might care to notice when you are in VR, though nothing compels you to: you are no longer aware of your physical body. Your brain has accepted the avatar as your body. The only difference between your body and the rest of the reality you are experiencing is that you already know how to control your body, so it happens automatically and subconsciously.

But actually, because of homuncular flexibility, any part of reality might just as well be a part of your body if you happen to hook up the software elements so that your brain can control it easily. Maybe if you wiggle your toes, the clouds in the sky will wiggle too. Then the clouds would start to feel like part of your body. All the items of experience become more fungible than in the physical world. And this leads to the revelatory experience.

The body and the rest of reality no longer have a prescribed boundary. So what are you at this point? You're floating in there, as a center of experience. You notice you exist, because what else could be going on? I think of VR as a consciousness-noticing machine."

- You Are Not A Gadget, Jaron Lanier, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2010. I requested permission to use this quote, but have received no response. I am therefore using it under the heading of 'fair use.' If Jaron or his representatives object, this article will be revised to eliminate the quote.

Now put this together with Don Juan's 'Dream Body', and Gotama's 'Mind-made Body'. Both of these are brought into existence by work of imagination rather than creations of software-created hardware ... or one might characterize the efforts of the software and hardware VR engineers as being crude efforts at creation of an imaginary alternative bodily experience which could be much more swiftly and skillfully accomplished by trusting the mind.

Lanier then goes on to speculate on the nature of identified with consciousness as the experience of existence. For the Buddhist this is not the issue. For us it is a given that the individual, in his blindness, creates identified-with conscious existence through his actions of mind, speech and body. Where the Buddhist can profit from Lanier's observation is in the acceptance of the notion that experience of self is not tied irredeemably to this or any body.

The Buddhist can also answer Lanier's question: "You notice you exist, what else could be going on?" by suggesting that there is no need for this conclusion. It is a struggle to force the idea of personal existence on something that can be shown to be out of control of the individual. Or you could say that the individual is intruding himself into a reality unnecessarily. Unnecessary for the rest of the phenomenological world to be occurring. A currently subjectively identified with existence (the so-called 'real' body) is creating subjective identified-with consciousness of existence through acts of mind, speech and body. At such a time as that consciousness strips off the blindness at the root of this creative effort and sees that the product is always going to be flawed and end badly, all that is needed to avoid that unpleasantness is to avoid that creating.

In the Virtual Reality world, without creating what they are calling an avatar (a representation of the self) the experience would still involve consciousness of things and others in that Virtual Reality world.

It would have helped if this book had had a Glossary.

homuncular flexibility: the ability of humans to identify with forms other than 'their' human bodies. 'Fungibility' is a term generally used in finance to describe a similar phenomena. Oil and gold are 'fungable': they can be used in trade without reference to a national currency.

Saturday, August 12, 2017

Previous upload was Monday, January 30, 2017

On the Intent Associated with Virtuous Behavior

"The fable of Ixion, who, embracing a cloud instead of Juno, begot the Centaurs, has been ingeniously enough supposed to have been invented to represent to us ambitious men, whose minds, doting on glory, which is a mere image of virtue, produce nothing that is genuine or uniform, but only, as might be expected of such a conjunction, misshapen and unnatural actions. Running after their emulations and passions, and carried away by the impulses of the moment, they may say with the herdsmen in the tragedy of Sophocles,

We follow these, though born their rightful lords,

And they command us, though they speak no words.

For this is indeed the true condition of men in public life, who, to gain the vain title of being the people's leaders and governors, are content to make themselves the slaves and followers of all the people's humors and caprices. For as the lookout men at the ship's prow, though they see what is ahead before the men at the helm, yet constantly look back to the pilots there, and obey the orders they give; so these men, steered, as I may say, by popular applause, though they bear the name of governors, are in reality the mere underlings of the multitude. The man who is completely wise and virtuous, has no need at all of glory, except so far as it disposes and eases his way to action by the greater trust that it procures him. A young man, I grant, may be permitted, while yet eager for distinction, to pride himself a little in his good deeds; for (as Theophrastus says) his virtues, which are yet tender and, as it were in the blade, cherished and supported by praises, grow stronger, and take the deeper root. But when this passion is exuberant, it is dangerous in all men, and in those who govern a commonwealth, utterly destructive. For in the possession of large power and authority, it transports men to a degree of madness; so that now they no more think what is good, glorious, but will have those actions only esteemed good that are glorious. As Phocion, therefore, answered king Antipater, who sought his approbation of some unworthy action, "I cannot be your flatterer, and your friend," so these men should answer the people, "I cannot govern and obey you." For it may happen to the commonwealth, as to the serpent in the fable, whose tail, rising in rebellion against the head, complained, as of a great grievance, that it was always forced to follow, and required that it should be permitted by turns to lead the way. And taking the command accordingly, it soon inflicted, by its senseless courses, mischiefs in abundance upon itself, while the head was torn and lacerated with following, contrary to nature, a guide that was deaf and blind. And such we see to have been the lot of many, who, submitting to be guided by the inclinations of an uninformed and unreasoning multitude, could neither stop, nor recover themselves out of the confusion."

Plutarch, Lives of Illustrious Men, translated from the Greek by John Dryden and others in 3 volumes. Volume III, pg 61-62, David McKay, no copyright or publication date.

![]() Majjhima Nikāya. The Bhikkhu Ñāṇamoḷi 3-volume manuscript used as the basis for the Bhk. Bodhi edited edition. "Manuscript" here means hand written! and his script is no easy thing to read. Note that the PDFs and zipped downloads are very large files.

Majjhima Nikāya. The Bhikkhu Ñāṇamoḷi 3-volume manuscript used as the basis for the Bhk. Bodhi edited edition. "Manuscript" here means hand written! and his script is no easy thing to read. Note that the PDFs and zipped downloads are very large files.

![]() MN 1 Ñāṇamoḷi.

MN 1 Ñāṇamoḷi.

![]() MN 2 Ñāṇamoḷi.

MN 2 Ñāṇamoḷi.

![]() MN 3 Ñāṇamoḷi.

MN 3 Ñāṇamoḷi.

[MN 1.1] The Root of All Dhammas, the Bhikkhu Ñāṇamoḷi translation. A typeset rendering of the Bhikkhu Ñāṇamoḷi translation of MN 1.1, published in Pāḷi Buddhist Review, Volume 5 #1-2, page 1, 1980.

The images for the pdf files were sent to me by Bhikkhu Hiriko at pathpress.org after I requested permission to publish this work from them. He informed me that this work is managed by Path Press, The Island Hermatage and The Forest Hermatage and that it was a matter of courtesy to check in with them concerning usage. I did e-mail both The Island Hermatage and The Forest Hermatage, but have received no answer. 'Perceiving that they agreed silently,' I am putting up these files with gratitude and the hope that this does not conflict with their wishes. If there is any objection by the Island Hermatage, or the family of Bhk. Nanamoli to our publication of this work on this site it will be removed immediately. Otherwise consider it published for the use of individual researchers seeking to determine precisely what changes were made by Bhk. Bodhi.

Monday, January 30, 2017

Previous upload was Saturday, December 31, 2016

![]() Majjhima Nikāya, [MN 8] Hoeing the Row, Olds, trans.

Majjhima Nikāya, [MN 8] Hoeing the Row, Olds, trans.

Mahā Cunda approaches the Buddha to ask how to eliminate ideas of 'I' and 'mine'. The Buddha's response is to give him pairs of opposites to be resolved upon, thought of, used as guides to follow, things leading upward and which will scour out ideas of 'I' and 'Mine.'

![]() Majjhima Nikāya,[MN 22] The Snake Simile Nyanaponika Thera, trans.

Majjhima Nikāya,[MN 22] The Snake Simile Nyanaponika Thera, trans.

A wide-ranging very famous sutta that begins with a forceful teaching on the dangers of indulgence in sense pleasures. This sutta contains two famous similies: the similie of the snake illustrating how a wrong grasp of the Dhamma is like taking hold of a poisonous snake from the wrong end; and the simile of the raft illustrating how the Dhamma should be used to attain its ends and then be let go. The sutta concludes with a thorough examination of the way 'not self' should be considered.

Mount Meru (Sumeru, Sineru)

DPPN: Sineru. A mountain, forming the centre of the world. It is submerged in the sea to a depth of eighty-four thousand yojanas and rises above the surface to the same height. It is surrounded by seven mountain ranges — Yugandhara, Sadhara, Karavīka, Sudassana, Nemindhara, Vinataka and Assakaṇṇa. On the top of Sineru is Tāvatiṃsa, while at its foot is the Asurabhavana of ten thousand leagues; in the middle are the four Mahādīpā [great islands or lands or continents] with their two thousand smaller dīpa.

Sineru is often used in similes, its chief characteristic being its unshakability (suṭṭhuṭhapita). It is also called Meru or Sumeru, Hemameru, and Mahāneru. Each Cakkavāla [world system] has its own Sineru, and a time comes when even Sineru is destroyed.

"... nay i had removed its very stone to the back side of Mount Káf."1

1 Popularly rendered Caucasus (see Night cdxcvi): it corresponds so far with the Hindu "Udaya" that the sun rises behind it; and the "false dawn" is caused by a hole or gap. It is also the Persian Alborz, the Indian Meru (Sumeru), the Greek Olympus, and the Rhiphæn Range (Veliki Camenypoys) or great starry girdle of the world, etc.

A vision attained by those who 'see', Mt. Meru is not a physical place in the ordinary world though it is a representation of a real perception from 'on high.'

To toss something beyond Mt. Meru (Mt. Káf) is to cast it out of this world.

— The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night, Volume 1, pg 72, translated by Richard F. Burton, Printed by The Burton Club for Private Subscribers only, 1885.

![]() Majjhima Nikāya,

Majjhima Nikāya,

![]() FD 2 A PDF file of the page-images of Further Dialogues II (MN 77-152). This is a very poor quality scan with 2 pages missing, no frontmatter and no indexes, just the suttas, but it will do to check the html files if that is desirable.

FD 2 A PDF file of the page-images of Further Dialogues II (MN 77-152). This is a very poor quality scan with 2 pages missing, no frontmatter and no indexes, just the suttas, but it will do to check the html files if that is desirable.

The html formatted Lord Chalmers, Sacred Books of the Buddhists translation, Further Dialogues of the Buddha, Vol. II.

[MN 115] Bahu-Dhātuka Suttaṃ, Diverse Approaches

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

The Buddha defines what it is that makes a person wise.

A very informative sutta when it comes to the study of equivalents in the Dhamma.

[MN 116] Isigili Suttaṃ, A Nominal List

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, the Piyadassi Thera translation and the Sister Upalavana translation.

The Buddha sings the praises of a number of paccekabuddhas.

A very old way of remembering the past practiced in Ancient Greece (where some teachers are reported to have memorized the entire contents of large libraries) and throughout the Ancient East, still practiced by some tribes in Africa. Before writing and the printing press, and the radio, and the TV and the computer and the i-phone, the mere recollection of a single word or name would bring to mind a much expanded story as handed down from generation to generation. In the Buddha's time it was expected that a person could at least remember the history of his family back seven generations on both sides. We see evidence in the udanas at the ends of chapters in the Pāḷi of how this technique was used to memorize the entire collection of suttas before it was written down. Recently 'rediscovered' this memory enhansing method can now be found advertised on late night TV and on the Internet whence you can pay a hefty sum to learn to make associations in the mind.

[MN 117] Mahā Cattārīsaka, Right Views Rank First

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, the Wisdom Publications Ñanamoli Thera translation edited by Bhikkhu Bodhi, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation and the Sister Upalavana translation.

In this sutta the Buddha teaches that there is a misguided way and a high way and that the high way may be undertaken in a low way and a high way depending upon one's point of view, the direction of one's effort and the set of one's mind.

Note in this sutta the definition of 'Sammā Diṭṭhi' High View. It is on this sutta that a certain school of Buddhism holds that any effort at accomplishment is mundane practice and that there is nothing to do to attain the super-mundane practice. If they have any logic to their reasoning it is because this so-called supermundane practice is made up entirely of letting go. But letting go is still kamma, action, something to be done and often requires great effort just to get to the point where letting go is possible. I am of the belief that the intent in this sutta was not to suggest two separate paths, but to create awareness that if a practice is pursued with grasping the result will not be the liberation one saught. In practice one will tread both paths, first with grasping and then upon becoming aware of the grasping, with letting go.

[MN 118] Ānāpāna-Sati Suttaṃ, On Breathing Exercises

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, the Wisdom Publications Ñanamoli Thera translation edited by Bhikkhu Bodhi, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation the M. Olds translation and the Sister Upalavana translation.

The Buddha explains how recollecting aspiration developed and made much of, completely perfects the four settings-up of memory; the four settings-up of memory, developed and made much of, completely perfects the seven dimensions of awakening; the seven dimensions of awakening, developed and made much of, completely perfects freedom through vision.

[MN 119] Kāyagatā-Sati Suttaṃ, Meditation on the Body

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, the Wisdom Publications Ñanamoli Thera translation edited by Bhikkhu Bodhi, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation and the Sister Upalavana translation.

The Buddha goes into detail concerning minding the body.

This sutta is identical with the section in the Satipaṭṭhana Suttas concerning body. What is unique about it is that it is divided from minding the breath which is described in the preceding sutta. Remember that the Buddha states that he considers breath and body to be equivalents.

[MN 120] Saṅkhār'uppatti Suttaṃ, Plastic Forces

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

The Buddha teaches how the intent to create experience for the self results in rebirth in accordance with the intent in a sequence that progresses from the intent to experience rebirth as a wealthy or powerful individual through a detailed list of gods to Arahantship.

Lord Chalmers here has both reverted to his previous translation of Sankhārā as 'plastic forces' and taken on to that the definition of it as being faith, virtue, instruction, munificence and understanding. This is not supported by the Pāḷi. There is no 'these five Sankhārā' there. In the 'wherever are these Sankhārā' the 'these' refers back to the previous set (fixing his heart, setting his heart, training his heart in this translation). He confirms his error in the following cases but breaks down towards the end, using there 'qualities'. He is not alone in his confusion. Both Bhk. Bodhi and Ms. Horner's translations of Sankhārā change in this sutta. The confusion results from their original translations, which, say I, should always have followed the Pāḷi etymology and been translated 'own-making' or at the least 'construction'.

[MN 121] Cūḷa Suññata Suttaṃ, True Solitude I

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, the Wisdom Publications Ñanamoli Thera translation edited by Bhikkhu Bodhi, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation, the M. Olds translation, the Nyanamoli Thera translation edited and arranged by Phra Khantipalo and the Sister Upalavana translation.

The Buddha teaches Ānanda a technique for reaching an undisturbed state empty of lust, hate and blindness.

[MN 122] Mahā Suññata Suttaṃ, True Solitude II

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, the Wisdom Publications Ñanamoli Thera translation edited by Bhikkhu Bodhi, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation, the M. Olds translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

The Buddha extoles living in solitude and describes the effort the student must make to return again and again to each stage of the path when upon evaluation of his accomplishments he realizes he is not yet satisfied that he is completely liberated.

[MN 123] Acchariya-abbhūta Suttaṃ, Wonders of the Nativity

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

Ānanda relates what he has heard about certain wonderous events that accompanied the birth of the Buddha.

[MN 124] Bakkula Suttaṃ, A Saint's Record

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

Bakkula utters a lion's roar to his old friend the wanderer Kassapa the Unclothed who is so impressed he joins the order and soon attains arahantship himself.

As received this sutta is flawed. It begins as a telling by an individual of the encounter of Bakkula with an old friend that he converts. Early on, however, there is interjected (Chalmers: 'intercalated') a refrain reputedly uttered by the Compilers. Presumably this was because the sutta was added to the collection at a late point and the compilers, to be forthright needed to make the fact known. It would have been better to have stated this at the start. As it is it has a disjointed feel which breaks the spell.

The sutta describes the wonderful scene of Bakkhula going from door to door among the bhikkhu's huts anouncing to the bhikkhus that he was going to die and if they wanted to witness the same they should come along now.

[MN 125] Danta-Bhūmi Suttaṃ, Discipline

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

The Buddha describes the course of training for a bhikkhu.

This sutta has in it the simile of two friends, one of whom climbs a mountain and describes what he can see from the summit. The other friend doubts such as is described. So then the first climbs down the mountain again and leads his friend by the hand to the top where he realizes that he could not see the sights because his view was obscured by the mountain. The mountain = blindness.

[MN 126] Bhūmija Suttaṃ, Right Outlook Essential

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

The Buddha explains that it is not enough to have hopes, aspirations, yearnings for freedom from pain, one must behave in a way that brings pain to and end for that to happen. He provides four similes to illustrate this point: trying to get oil by pressing sand, trying to get milk by pulling a bull's horn, trying to get butter by churning water, and trying to light a fire with a wet sappy stick.

[MN 127] Anuruddha Suttaṃ, As They Have Sown

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

Venerable Anuruddha explains the difference between 'boundless' freedom of mind and 'wide-spread' freedom of mind and then answers further questions concerning the manner in which 'wide-spread' freedom of mind manifests its results in rebirth in a deva world.

[MN 128] Upakkilesa Suttaṃ, Strife and Blemishes

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

The Buddha is not able to halt the argument and contention of the Saṅgha in Ghosita's vihara in Kosambī and so moves on to Visit Bhago in Balakallonakara village where he teaches him Dhamma and then he visits the Anuruddhas staying in the Eastern Bamboo Grove there. There he teaches the Anuruddhas in great detail the process of eliminating the obstructions to clairvoyant sight and describes the method of jhāna practice in threes which he himself used to attain arahantship.

An absolutely invaluable sutta when it comes to developing insight, clairvoyance and the jhānas.

Developing Psychic Powers

and

Jhāna Practice that Leads to Awakening

Being an analysis of Majjhima Nikāya, Sutta 128

by

obo

After first having understood the goal, having trained in ethical thinking and behavior, having trained in self-control to the point where living intent on the goal is such as to be able to say of one's self that one is living carefully, ardently and self-directed [pahitattā]:

Intent on stilling, calming and tranquilizing the breath or on some other subject that absorbs the attention, at a point where one is fully alert and attention has been fully focused on that object to the exclusion of external distractions, there will occasionally appear a brilliant flash of white light [obhāsa] something like a flash of sunlight in a dark room; and there will occasionally appear clear mental visions [dassanañ ca rūpānaṃ: and seeing forms (in the mind)]. But these will quickly vanish.

To extend the duration of these phenomena it is necessary to ask yourself: What were the signs [nimitta] of the driving forces, what was it that resulted in the vanishing of the light and the perception of forms?

Note the direction of this thinking: it is not "how do I prolong the light/visions", but "what brought them to an end?" The implied presumption is that the light/visions will be there in one who is in a state of calm impassive wakeful serene focused observation [samādhi] if what is causing them to vanish is eliminated.