What's New?

What's New?

What does that mean?

![]()

2016

Saturday, December 31, 2016

Previous upload was Monday, November 20, 2016

What does it mean when the Arahant states: "Debt-free (anaṇa) am I!"?

When one comes to a complete halt, stops the world, ends own-making, makes no new kammawhether of mind, speech or body, what remains is only the results of old kamma. Old kammais the debt. It is debt in the sense that kammais energy which, like electricity when it contacts the filiments in a lightbulb produces illumination needs an object to have an effect and is a force in nature out of balance until it is grounded out. The objects of kamma, the filiments, are the subjective mind and the five lower senses. No longer associating with body, sense-experience, perception, own-making or individualized consciousness, the Arahant no longer subjectively experiences the effects of returning kamma. There is no longer a subjective existing being there. His experience of such kammathat remains to be experienced to ground out is as of a detached observer. His effort at having detached himself from subjective existence is his having paid off his debt. This is the meaning of being debt-free.

See for example: — SN 1.11.17

Setting Priorities

The Idea of Death

As a Guide to Forming Priorities

You only need this one idea: You could die at any time now. In the next couple of years, or in the next year, in the next month, in the next week, tomorrow, in the next minute. You just don't know. The only reasonable way to deal with this is to act with the idea that you could die at any time from the next minute on.

Make Death your constant companion. With that idea taken seriously you can set up life priorities which will be rewarding now in the relief from stress of worry about future regret and will give you at the end the satisfaction of having done your best to meet the challenges of life in a reasoned manner.

Setting priorities is also hugely rewarding in this material world. You accomplish much more and what you accomplish assumes an order which builds on your personal growth.

Do, for yourself, that which you wish to have done or think you ought to have done before you die. Or said another way, do what you would regret not having done before you die.

Deal with all beings as though it were the last time you would be dealing with them ... before they die ... before you die.

Some sub-sets of these might be: broadening and deepening one's knowledge of the Dhamma; training yourself not to deal with people dismissively (or worse); expressing gratitude; paying off debts; righting wrongs done; doing good works.

Setting priorities is a complicated process. One's list of priorities will change over time. Priorities will change in the context of your learning. Some priorities influence other priorities so changes in one set will force changes in another. Be flexible. Do not hang on to a set of priorities just because it has served you well in the past.

This one consideration, considering the idea of death, will serve well as an over-riding guide for the setting of most lists of priorities.

■

Who's On First?

#1. Yourself: If you don't take care of yourself first, how will you be able to take care of others?

Close Family

Relations,

Friends,

Workers,

Teachers,

Bhikkhus and holy men of good moral conduct

Real People face-to-face

Real people at a distance: over the phone, via letter, e-mail ...

Virtual people: via essays, books on or off-line, blogs, tweets

■

What's Up?

Giving: Generosity

#1. Food

Clothing

Medicine

Shelter

The Dhamma

■

When?

To one in need

when you are in need

to one arriving

when you are arriving

to one departing

after you have departed

when the heart feels the desire

■

The Eight-Dimensional Way

as A Set of Priorities

#1. High Working Hypothesis

#1. 'This' is Pain

#2. This pain results from Thirst

#3. To End the Pain, End the Thirst

#4. This is The Way: High Working Hypothesis, High Principles, High Talk, High Works, High Lifestyle, High Energetic Self-Control, High Mind, High Getting High, High Vision and High Detachment

#2. High Principles

#1. Let Go

#2. Let Go Harming Living Beings

#3. Let go of Mental Cruelty

#3. High Talk

#1. Let go saying what is not true,

#2. deceitful speech, harmful speech, cruel speech, slander, distasteful speech

#4. High Works

#1. Let go harmful deeds,

#2. Taking what has not been given,

#3. Saying what is not true,

In your deeds, commerse, or working of magic charms

#5. High Lifestyle

Adopt letting go of what you can see for yourself is an unskillful form of behavior as a style of life.

#6. High Energetic Self-Control

#1. Restrain from unskillful things that have arisen in the present,

#2. Refrain from unskillful things that have not yet arisen,

#3. Obtain skillful things that have not yet arisen

#4. Retain skillful things that have arisen in the present.

#7. High Mind

#1. Live in a body, #2. in sense experience, #3. in the heart and #4. in the Dhamma, seeing these things as they are, seeing how they arise, seeing how they decline, seeing how they pass away, watchful and self-aware, letting go of indulgence in anger and depression, bound up in nothing at all in the world.

#8. High Getting High

#1. Learn to appreciate the peace and calm of solitude,

#2. Learn to enjoy the serene life,

#3. Learn to enjoy the ease of living alert and recollected,

#4. Learn to appreciate the clarity of detachment

#9. High Vision

#1. See the Four Truths as they really are, understanding

'This' being, that happens;

with the absense of 'This', the absense of that.

#10. High Detachment

Seeing from the point of view of High Vision, let that go and form no new point of view and see the detachment from points of view as freedom and in this freedom, see the freedom of Nibbāna and know:

This is having left behind rebirth,

This is having lived the Godly life,

This is having done duty's doing,

In this way there will be no more It'n-n-at'n Me!

Separating the Wheat from the Chaff

There are those who declare of a theory of salvation, enlightenment or awakening:

"This Teaching

is the Only Real Truth —

everything else is lies."

Here, in This Teaching, we do not accept such a statement.

■

Here, what we ask ourselves

is whether those who make such statements in the present,

actually know and see

of their doctrine proclaiming salvation, enlightenment or awakening that:

"This Teaching

is the Only Real Truth —

everything else is lies."

Or whether the teachers of those who make such statements,

or the teachers of their teachers,

or the originator of that teaching

actually knew and saw

of that doctrine proclaiming salvation, enlightenment or awakening that:

"This Teaching

is the Only Real Truth —

everything else is lies."

■

Here, in This Teaching,

we examine what the originators of that teaching,

actually did and said.

Here, in This Teaching,

we examine what the teachers of that teaching,

and the proclaimers of that teaching

actually do and say.

■

These five are unreliable bases for making the declaration:

"This Teaching

is the Only Real Truth —

everything else is lies."

Belief, (Saddhā),

its pleasing appeal, (ruci)

the fact that it follows from what has been heard was the Truth, (anussava),

the fact that has been constructed from the pondered over, (ākāra-pari-vitakko),

the fact that it is a view that accords with accepted knowledge, (diṭṭhi-nijjhānakkha).

Why not?

Because a thing believed to be true may be false;

and a thing believed to be false may be true.

Beliefs that please may be false;

and beliefs that displeases may be true.

Things which follow from what has been heard was the Truth may be false;

things which do not follow from what has been heard was the Truth may be true.

Things which are in accord with accepted knowledge may be false;

things which are contrary to accepted knowledge may be true.

■

Belief in a Truth,

being pleased with it,

passing a doctrine along,

ponderiing it well,

and causing it to be accepted knowledge

serve as ways of preserving a Teaching.

Simply because a Teaching has been preserved

is not sufficient to justify making the declaration:

"This Teaching

is the Only Real Truth —

everything else is lies."

For the statement to be made of a Teaching that:

"Well taught is this Dhamma by an Awakened One

who saw for himself,

teaching it afterwords to men and gods.

A saving, enlightening, awakening Dhamma.

A thing to be known and seen for one's self by the intelligent,

with results visible in this world,

not a matter of Time.

helpful in the beginning,

helpful in the middle,

helpful at the end,

a liberating thing,

leading onwards to dispassion,

letting go, giving up

culminating in the complete destruction of pain

deathlessness, freedom, utter detachment, Nibbāna."

There must also be

awakening to its truth.

■

For awakening to the truth of a Teaching

one must examine its originator or its teacher

concering three states:

States of greed (lobha)

States of hate, (dosa)

States of confusion (moha)

thus:

Does, or did this teacher exibit

through his speach and bodily actions

such evidence of greed in his mind

that he would say he knew and saw

when he did not know and see?

Or would he be capable

because of greed

of leading others to courses of action

which would be harmful to them?

If upon examination it is found

that that person's speech accords with his actions

and this conduct is not that of a greedy person,

and that that person's teaching is deep, subtle, leads to stilling, calming and tranquilizing the mind and body;

is reasonable, wise, peaceful;

leading on to letting go of harmful, low, common, un-dignified, unaristocratic states

and the attaining of utter freedom of detachment;

not something that could be taught by the greedy,

then he should examine that teacher as to states of hate.

■

Does, or did this teacher exibit

through his speach and bodily actions

such evidence of hate in his mind

that he would say he knew and saw

when he did not know and see?

Or would he be capable

because of hate

of leading others to courses of action

which would be harmful to them?

If upon examination it is found

that that person's speech accords with his actions

and this conduct is not that of a person full of hate,

and that that person's teaching is deep, subtle, leads to stilling, calming and tranquilizing the mind and body;

is reasonable, wise, peaceful;

leading on to letting go of harmful, low, common, un-dignified, unaristocratic states

and the attaining of utter freedom of detachment;

not something that could be taught by one who hates,

then he should examine that teacher as to states of confusion.

■

Does, or did this teacher exibit

through his speach and bodily actions

such evidence of confusion in his mind

that he would say he knew and saw

when he did not know and see?

Or would he be capable

because of confusion

of leading others to courses of action

which would be harmful to them?

If upon examination it is found

that that person's speech accords with his actions

and this conduct is not that of a confused person,

and that that person's teaching is deep, subtle, leads to stilling, calming and tranquilizing the mind and body;

is reasonable, wise, peaceful;

leading on to letting go of harmful, low, common, un-dignified, unaristocratic states

and the attaining of utter freedom of detachment;

not something that could be taught by one is confused,

then one may reasonably place faith in that individual.

■

To this extent

there is the method of separating the wheat from the chaff,

but there is not yet awakening

to knowing and seeing this Dhamma.

■

Placing faith in This Dhamma and This Teacher;

one should approach this Dhamma;

approaching,

one should pay attention;

paying attention,

one should listen carefully;

listening carefully,

one will hear the details of this Dhamma;

hearing this Dhamma,

one should remember what has been heard;

what one has remembered

should be pondered in mind

and tested by implementation

in one's thoughts, words and deeds;

through testing the Dhamma,

one will see its veracity;

seeing the truth of this Dhamma,

one will approve of it;

approving, one will be pleased;

pondering the results,

approving of the results,

pleased,

one redoubles one's effort,

exerts one's self whole-heartedly,

becomes resolved on attainment;

become resolved on attainment,

one realizes the Dhamma,

knowing it and seeing it for one's self

by having penetrated it

through the knowledge, wisdom and vision

generated by this method.

■

To this extent he can say:

"I know, I see."

■

To this extent what has been accomplished

is awakening to knowing and seeing This Dhamma,

but it cannot yet be said

that there is attainment of the goal of This Dhamma.

■

For the attainment of the goal of This Dhamma

there must be walking-the-talk,

making it an encompasing reality,

that which follows from This Dhamma must be unbroken in practice.

In a word,

one must become Dhamma.

■

In the service of walking-the-talk,

making it real,

unbroken practice,

becoming Dhamma,

is starting;

In the service of starting

familiarity.

In the service of familiarity

is pondering and evaluation;

In the service of pondering and evaluation,

is exertion.

In the service of exertion,

is desire to attain.

In the service of desire to attain,

is approval of This Dhamma.

In the service of approval of This Dhamma,

is testing the truth.

In the service of testing the truth,

is remembering This Dhamma.

In the service of remembering This Dhamma,

is knowledge of This Dhamma.

In the service of knowledge of This Dhamma,

is lending a ready ear.

In the service of lending a ready ear

is paying careful attention.

In the service of paying careful attention

is approaching with an open mind.

In the service of approaching with an open mind is faith.

See also:

![]() Majjhima Nikāya,

Majjhima Nikāya,

![]() FD 2 A PDF file of the page-images of Further Dialogues II (MN 77-152). This is a very poor quality scan with 2 pages missing, no frontmatter and no indexes, just the suttas, but it will do to check the html files if that is desirable.

FD 2 A PDF file of the page-images of Further Dialogues II (MN 77-152). This is a very poor quality scan with 2 pages missing, no frontmatter and no indexes, just the suttas, but it will do to check the html files if that is desirable.

Note: In this volume Lord Chalmers has changed his translation of sankhārā (Olds: own-making; Horner: habitual tendencies; Rhys Davids: activities; Bhk. Bodhi: formations aggregate; Bhk. Thanissaro: fabrications;) from 'plastic forces' to 'constituents'. We have no explanation from Lord Chalmers in Volume I of why he translated this term as he did, and there is apparently no new introduction in Volume II which might have explaned his change.

The html formatted Lord Chalmers, Sacred Books of the Buddhists translation, Further Dialogues of the Buddha, Vol. II.

[MN 77] Mahā Sakuludāyi Suttaṃ, The Key to Pupils' Esteem,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, the Wisdom Publications' Ñanamoli Thera translation, edited and revised by Bhikkhu Bodhi, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

In a discourse which amounts to a full course in Awakening the Buddha teaches Sakuludayi and his followers the reasons his disciples admire and follow him.

[MN 78] Samaṇa-Maṇḍikā Suttaṃ, The Suckling,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, the Bhikkhu Thaissaro translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

The Buddha teaches Five-tools, the carpenter about ethical standards, their origination, their stopping and the way to go about causing their stopping; intentions, their origin, their stopping and the way to go about their stopping.

[MN 79] Cūḷa Sakuludāyi Suttaṃ, So-Called Perfection,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

In another encounter with the Wanderer Sakuludayi, the Buddha explains what it is in his system that constitutes perfection and which is the state beyond bliss that his followers attain.

[MN 80] Vekhanassa Suttaṃ, More So-Called Perfection,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

The wanderer Vekhanassa has come to challenge Gotama but is shown to be holding a viewpoint based entirely on hearsay which breaks down under close questioning. He is then led to acceptance of the more realistic doctrine of the Buddha.

[MN 81] Ghaṭīkāra Suttaṃ, The Potter's Devotion,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

The Buddha's wandering brings him to a spot where the Buddha Kassapa once taught and where at that time in a previous birth as Jotipala, Gotama had to be dragged by the hair to visit this Buddha and hear his Dhamma.

Of course there developed a great controversy over this sutta concerning the idea that a Buddha is 'self-awakened', not brought to awakening by having heard another's doctrine. But there is hearing a doctrine and even professing great belief in it without understanding a word of it or what it was intended to accomplish. Gotama makes the statement that it was under this Buddha (Kassapa Buddha) that he '... lived the higher life for supreme enlightenment in the future.' This can mean no more than that he lived within the rules of a bhikkhu with the intent to attain awakening. It says nothing about having accomplished even the first step of this desire. See: KV Appendix 6a and KV.04.08 for more details.

Four Inspiring Spurs

Upanīyati loko addhuvo;||

Attāṇo loko anabhissaro;||

Assako loko sabbaṃ pahāya gamanīyan;||

Ūno loko atitto taṇhādāso.|| ||

■

Carried off, the world, unstable;

No refuge, the world, without protective power;

Unowned, all the world, out of hand, done gone;

Needy, the world, unsatisfied, hunger-enslaved.

[MN 82] Raṭṭhapāla Suttaṃ, Of Renouncing The World,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation, the Walter Lupton translation, the Wisdom Publications' Ñanamoli Thera translation, edited and revised by Bhikkhu Bodhi, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

The story of Ratthapala who, inspired by a Dhammatalk given by the Buddha wishes to enter the order but is refused the permission of his parents. He vows to die on the spot unless he receives permission and after many pleadings by his parents and friends finally gets his parents concent. He thereafter quickly becomes arahant. On revisiting his family he is first unrecognized and subjected to abuse, then his father tries to tempt him to return to the world with gold and his former wives. He is not persuaded and delivers a sermon in verses on the subject of the pains in the world. Still later he discourses to the king on four doctrines of the Buddha concerning the futility of living in the world.

[MN 83] Makhādeva Suttaṃ, Of Maintaining Great Traditions,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

The Buddha relates a past life and uses it to inspire Ānanda not to be the last of the line to live by the Eightfold Path.

[MN 84] Makhādeva Suttaṃ, Of Maintaining Great Traditions,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the J.R.A.S, 1894 Chalmers translation, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

King Avantiputta of Madhura has heard a boast by the Brahmins that they were superior to all other peoples. He asks Venerable Kaccana the Great about this and receives a discourse showing that this is a lot of hot air. A very good example of the use of questions to bring about understanding in a questioner.

[MN 85] Bodhi-Rāja-Kumāra Suttaṃ, Aptness to Learn,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

Prince Bodhi is given a discourse in refutation of the idea that the end of pain is to be got through suffering pain. A sutta built around circumstances of the Buddha's practice of austerities and the practice that lead to his awakening.

[MN 86] Aṅgulimāla Suttaṃ, The Bandits Conversion,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, the Edmunds translation, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation the Wisdom Publications' Ñanamoli Thera translation, edited and revised by Bhikkhu Bodhi, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

The Majjhima Nikāya version of the story of Angulimala, the bandit/murderer who, after killing 999 people, was converted by the Buddha and became an Arahant.

See also: Garland of Thumbs (discussion)

The Sutasoma-Jātaka (No. 537)

The verses ascribed to Aṅgulimāla are at Thag. 806 ff.

[MN 87] Piya-Jātika Suttaṃ, Nullius Rei Affectus*,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation and the Sister Upalavana translation.

*I do not see how to translate this — 'Nothing comes from Affection'?) Queen Mallika convinces King Pasenadi of the truth in the Buddha's saying that grief and lamentation, pain and misery and despair are born of affection, originate in affection.

Sanity Test

Test your version of Sanity.

The Buddha says:

"Born of love is

grief and lamentatin,

pain and misery,

and despair."

Are you saying to yourself:

"That is not true! All our joys are born of love!"

or

"So what? We have to take the bad with the good."

or are you saying:

That is the voice of Sanity in a world gone blind and is, at the least, a truth by which I must try and direct my course.

'Love,' Pāḷi 'Piya', is not 'wishing you well' or 'regarding with a heart of friendliness,' Pāḷi 'metta', which is a fine thing; it is attachment to 'my affection for you'. Love is a need for the pleasure felt by the self when in contact with or pondering another. It is an intense form of immediate kammic feedback. One ponders the pleasant feature of another and liking is generated which produces a pleasant sensation and like the feedback that results from placing a microphone too close to the speaker it is connected to, an intense cycle of liking and pleasant sensations results. Alteration in the source of the pleasant sensation results in pain felt at the loss of the pleasure. Always. To the degree of the attachment. To say that indulging in this behavior with its transient pleasure and certain pain is anything less than insanity is insanity.

[MN 88] Bāhitika Suttaṃ, On Demeanour,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

In an exchange between Ānanda and King Pasenadi Ānanda defines what is offensive and what is inoffensive conduct of body, speech and thought and is thanked by the king with a gift of a fine piece of cloth.

[MN 89] Dhamma-Cetiya Suttaṃ, Monuments of the Doctrine,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

Raja Pasenadi pays a visit to the Buddha and shows great respect and enumerates the reasons for his great respect.

[MN 90] Kaṇṇakatthala Suttaṃ, Omniscience and Omnipotence,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

King Pasenadi questions the Buddha about omniscience, the difference between the casts, and about the exisence and destinies of the gods and Brahma.

[MN 91] Brahmāyu Suttaṃ, The Superman,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

The Brahmin Brahmayu, at the age of 120, is converted and becomes a non-returner when he sees the 32 marks of a great man in Gotama and is taught a gradual course in Dhamma.

This sutta has several interesting features. The casual mention of this Brahmin as being 120 years old and 'reaching life's termination'! is only one of several such examples of life expectancy at the time. The 32 marks of the Superman are always a good challenge. Try and work out in your mind how these marks can be both physically visible and representative of superiority or special powers in a being. Note the manner of the exchange; that is, in verse. This was a frequent form of debate and required that the one challenged reply to the challenge in the form of the challenge. Verse required a reply in verse, etc. Today such debates are still to be found in Spain and Arab countries and in musical battles in many countries. Also note the extreme politeness and respect in the brahmin's behavior.

[MN 92] Sela Suttaṃ, The Real Superman,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

Keniya, a matted hair ascetic is greatly satisfied by a teaching of the Buddha and invites him and the order of bhikkhus, 1200 in number to a meal for the next day. In the meantime Sela the Brahman seeing the preparations for the meal being made by Keniya, is told that it is for an Awakened One. Sela is stirred by the idea of an Awakened One and visits the Buddha immediately and he, and his 300 followers are converted. The next day the Buddha and the order of bhikkhus, now some 1500 in number show up for the meal.

[MN 93] Assalāyana Suttaṃ, Brahmin Pretentions,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation and the Sister Upalavana translation.

A debate between a Brahmin and the Buddha concerning the relative merits of the casts. A thoroughly rational and convincing set of arguments for the position that it is individual merit, not birth that distinguishes one man from another.

Well, this is not just a debate with good logical points being made. It is withering assault on a stupid idea that twists the argument into a knot and tosses it aside. It is to the credit of Gotama's opponent that he never believed he would win the argument in the first place and that he so gracefully acknowledges defeat in becoming a disciple of the Buddha.

An interesting point that comes up in passing is the notion of how conception occurs and the role in that of the Gandhabba. The role of the Gandhabba is questioned by some. Here it is clear that the Gandhabba is the spirit of the being to be reborn. This is not some guardian spirit or musical chorus attending the event to make sure of its success. Further, though there is no mention of this here, or elsewhere that I know of, there is competition for this role in the event. Fierce competition, as with the stream of millions of spermatozoa competing to be the one fertalizing the one egg. Imagine then, on top of the competition between Ghandhabbas seeking rebirth, and the competition between the millions of spermatazoa coming down one individual's ... um ... stream, the competition between beings for the roles as the participating male and female in the picture, and you begin to get some sense of the difficulty of finding rebirth again as a human, once death has overtaken the body.

[MN 94] Ghoṭamukha Suttaṃ, Against Torturing,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

The Brahman Ghotamukha is converted by the bhikkhu Udena with a discourse on the four types of persons found in the world.

[MN 95] Cankī Suttaṃ, Brahmin Pretensions,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, the Wisdom Publications' Ñanamoli Thera translation, edited and revised by Bhikkhu Bodhi, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation and the Sister Upalavana translation.

The Buddha points out the flaws in reliance on faith, inclination, report, consideration of reasons, reflection on and approval of an opinion and describes the path that leads to seeing the truth of a proposition for one's self.

[MN 96] Esukārī or Phasukārī Suttaṃ, Birth's Invidious Bar,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

The Buddha teaches brahman Esukari with a very powerful sutta on the error of discrimination by birth or color, or wealth.

[MN 97] Dhānañjāni Suttaṃ, The World's Claims,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation and the Sister Upalavana translation.

Sariputta instructs the brahman Dhananjani about how to rise above careless behavior and attain the Brahmā world.

[MN 98] Vāseṭṭha Suttaṃ, The Real Brahmin,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

The Buddha resolves the dispute between two brahman youths. One held the belief that a brahman was a brahman because of birth, the other that a brahman was a brahman because of deeds. In many examples the Buddha shows that one is a brahman because of deeds.

This sutta is cut off mid-way because of missing pages in my copy. Links are given to other translations.

This sutta is hard to swallow as an authentic utterance of the Buddha. The point is within the scope of the Dhamma, the argument over all is reasonable, but the details are carelessly put and subject the whole argument to rebuttal. Gotama is not a careless speaker. For example it is said here that there is no difference in color. (Color is also 'cast', but here it uses as an example the differences in color between animals.) But we see there are differences in color. We can see differences in some of the other characteristics which this sutta claims are not different. The human being can be bread to bring out differences like any other animal and that has happened over time. The idea is that any differences in physical characteristics between human beings resulting from birth are superficial in the sense that they are not taken into consideration in the determination of nobility of character.

Personally I would put this sutta to one side as being doubtful. It seems probable that it was an elaborated version of some real discussion, but the story-teller got carried away with himself.

[MN 99] Subha Suttaṃ, Real Union with Brahmā,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

Subha asks the Buddha about what he thinks of a number of Brahman doctrines.

[MN 100] Sangārava Suttaṃ, Yes, There Are Gods,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

The Buddha converts the brahman youth Sangarava with a discourse about the different types of people that claim to be supremely awakened. He tells Sangarava about some of the events of his struggle for awakening and the method he discovered for doing so.

[MN 101] Devadaha Suttaṃ, Jain Fatuities,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation, the M. Olds paraphrase 'translation', and the Sister Upalavana translation.

The Buddha gives a detailed refutation of the doctrine of the Jains and sets forth his counter-argument in his method for the ending of kamma.

[MN 102] Pañcattaya Suttaṃ, Warring Schools,

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation.

In this sutta the Buddha outlines various views about the nature of the real, essential self and the world, past, future and present and points out that these views are all speculative and that for true satisfaction and liberation one must let go of all that which has been constructed, including speculative opinions.

This sutta is seriously flawed as we have received it. There is an obvious section missing, it begins in an untypical way, and there is a disjoint between its stated purpose in the beginning and the way it concludes. It looks like a fragment that has been expanded by the commentator(s) blindly appending an orthodox set of teachings which are nevertheless out of place here. Neither Chalmers nor Horner notice the missing segment. Bhk. Bodhi has it correctly (though he leaves it explained in a doubtful manner by the commentator) but his version of this sutta was not among those released for free distrbution. Put this one aside, or take just the beginning 'summary' and see how the point is understanding how the set of five can be encompassed by the set of three. Here is my version of the opening section:

Three-from-Five

I HEAR TELL:

Once Upon a Time, The Lucky Man, Sāvatthī-town

Anāthapiṇḍika's Jeta Grove,

came-a revisiting.

There then, the Lucky Man addressed the beggars:

"Beggars!" he said.

And, the beggars responding "Bhante!",

the Lucky man said this to them:

There are, beggars, some shaman-brahmin,

of Time hereafter,

undertaking of the herafter

a view-theory of the herafter,

that propose, in various formulations,

a definitive claim.

1. Thus some claim:

'Percipient, the self is fine after death.'

2. Thus some claim:

'Non-percipient, the self is fine after death.'

3. Thus some claim:

'Neither-percipient-nor-non-percipient, the self is fine after death.'

4. Or they declare the chopping off,

destruction,

non-existence of any future mind for beings.

5. Or some claim Nibbāna in this seen thing.

■

1. Thus they declare of self its being fine after death.

2. Or they declare that any future mind for beings

is chopped off,

destroyed,

non-existent.

3. Or again some claim Nibbāna in this seen thing.

■

Thus do these five come to three

the three come to five.

Thus is the encapsulation of the three-from-five.

[MN 103] Kinti Suttaṃ, Odium Theologigum,*

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, the Wisdom Publications' Ñanamoli Thera translation, edited and revised by Bhikkhu Bodhi, the Sister Upalavana translation, and an outline of the sutta by M. Olds.

*Theological Dispute. In this sutta the Buddha outlines the various ways in which argument and contention arise; the ways bhikkhus should attempt to resolve argument and contention; and the way one should respond if asked if one were the person who resolved an argument or raised another from the dark into the light.

[MN 104] Sāmagāma Suttaṃ, Unity and Concord

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, the Wisdom Publications' Ñanamoli Thera translation, edited and revised by Bhikkhu Bodhi, and the Sister Upalavana translation

Hearing of the great disorder among the followers of Nataputta the Jain upon his death, Ānanda approaches the Buddha about taking measures to insure it does not happen in his sangha. The Buddha then explains to Ānanda those things which will retain unity in the order.

[MN 105] Sunakkhatta Suttaṃ, Leechcraft

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation

The Buddha shows Sunakkhatta a path to Nibbāna together with several similes to help illustrate his points.

[MN 106] Āneñja-Sappāya Suttaṃ, Real Permanence

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation

The Buddha elaborates a hierarchy of stages in the realization of Nibbāna with unshakability as the initial point of entry, that is, Streamwinning.

A very important sutta in that it describes the stages of progress towards Nibbāna not with the usual 'Streamwinner', 'Once-returner', 'Non-Returner', 'Arahant', but gives us a perspective on these by describing stages to Nibbāna in terms of attainment of unshakability, the Realm of No-things-had, the Realm of Neither-perception-nor-non-perception, Crossing the Flood, and the Aristocratic Release.

[MN 107] Gaṇaka-Moggallāna Suttaṃ, Step by Step

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation

The Buddha teaches a brahman his Gradual Course of instruction and answers his question as to why some attain Nibbāna this way and why some do not.

[MN 108] Gopaka-Moggallāna Suttaṃ, Gotama's Successor

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation, the Wisdom Publications' Ñanamoli Thera translation, edited and revised by Bhikkhu Bodhi, and the Sister Upalavana translation

Ānanda responds to questions about how the order can maintain harmony without a designated leader.

Bhikkhu Thanissaro's introduction to this sutta:

This discourse presents a picture of life in the early Buddhist community shortly after the Buddha's passing away. On the one hand, it shows the relationship between the monastic community and the political powers that be: the monks are polite and courteous to political functionaries, but the existence of this discourse shows that they had no qualms about depicting those functionaries as a little dense. On the other hand, it shows that early Buddhist practice had no room for many practices that developed in later Buddhist traditions, such as appointed lineage holders, elected ecclesiastical heads, or the use of mental defilements as a basis for concentration practice.

[MN 109] Mahā Puṇṇama Suttaṃ, The Personality Craze

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation

The teacher of a group of bhikkhus leads them to arahantship by asking a series of questions of the Buddha.

An example of persons attaining Arahantship while listening to a discourse.

[MN 110] Cūḷa Puṇṇama Suttaṃ, Bad Men and Good

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation

The Buddha discourses on the qualities of the bad man and those of the good man.

This sutta, as well as describing the bad man and the good man, brings up the interesting idea that it is not possible for a bad man to "know" a bad man or a good man. The idea is that it is not possible for a person to see as a fault in another a fault he himself does not believe is a fault or a virtue he does not think is a virtue. I think this does not mean, for example, that the liar cannot tell another liar. He is just unable to see a fault in telling lies. In other words what he cannot see is not the fault, but the goodness or badness of the qualities. There are those who have faults they understand as faults and I think it does not contradict this sutta when we find that these persons are sometimes able to acknowledge in someone else the goodness that they do not themselves possess. Indeed this is a necessary pre-requisite for undertaking the effort at salvation taught by the Buddha.

[MN 111] Anupada Suttaṃ, The Complete Course

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation, the Wisdom Publications' Ñanamoli Thera translation, edited and revised by Bhikkhu Bodhi, the M. Olds translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation

This Sutta describes how Sariputta attained the goal through tracking down the essential factors necessary for insight.

This is a very interesting and unique sutta as is evidenced by the number of translations we have. In it we find the details of the jhānas described in more than the usual detail, and we have the over-arching method which is: observation of the component parts of a mental state; tracing them back to their point of origin; following them back to their point of ending; drawing the conclusion that these are ending things and do not constitute that which is self or belonging to self; and then separating one's self from them, becoming detached. Probably the most instructive sutta when it comes to developing and using the jhānas to attain detachment.

[MN 112] Chabbisodhana Suttaṃ, The Sixfold Scrutiny

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, the Wisdom Publications' Ñanamoli Thera translation, edited and revised by Bhikkhu Bodhi, the M. Olds translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation

The questions that should be put to one who has stated that for him rebirth is left behind, lived is the best of lives, done is duty's doing, there is no more being any sort of an 'it' at any place of 'atness' left for him; i.e., he has declared arahantship.

Here the Buddha has specifically used this formula for declaring arahantship. This is possibly because the term Arahant was used at the time to designate an honorable (worthy) person other than an arahant. So by using this specific formula the exact meaning of the term in this context is unmistakable.

[MN 113] Sappurisa Suttaṃ, Attitudes, Good and Bad

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation

The Buddha gives the bhikkhus a course leading to Nibbāna by way of contrasting the attitudes of the good man and the not so good man to each stage of the process.

Another very important sutta for meditators. At the point in this sutta where he begins describing the pride of a bad man in his accomplishments regarding the jhānas, we find the statement:

'Paṭhamajjhāna- [through to the n'eva-saññā-nāsaññāyatanaṃ] -samāpattiyā pi kho atammayatā vuttā Bhagavatā:|| ||

'Yena yena hi maññanti,

tato taṃ hoti aññathā' ti.|| ||

Of just this not-'Thus'-made acquirer of the First- [~+] jhāna then, the Lucky Man has said:

'In whatever way, by whomsoever such is imagined,

from that it becomes otherwise.

1 atammayatā Not in PED. A + TAṂ + MAYATA 'Thus' meaning awakened. But the explanation used by Ms. Horner serves just as well. The Awakened One is one who is Thirst-Freed'.

For a person who is not Arahant, all the jhānas from the first to the ending of perception and sense experience are states 'in the world'. They, in sequence, or from one only, are but a path to detachment, Nibbāna. Until the point where they are let go they are one and the same in their nature as part of the world: they are transient and do not belong to one though the 'not-Thus-made' imagines them to be 'acquired' 'by' 'himself' though they are none of these things. Subsequent to their being let go, they are let go and are seen as transient and not belonging to one.

The person not free from desire attains jhāna as a possession, not as a step along the way, itself to be seen as transient and not belonging to self and to be let go. He has imagined the state from what he has conceived it to be prior to attaining it and (however accurately he may have imagined it, as, for example, from a previous attainment) has therefore been chasing the past and that which he attains, upon its being attained, is not what he imagined, but something different and still 'in the world'.

In the same way a person experiencing hunger, remembers that which satisfied his hunger in past time and sets his mind on attaining that satisfaction again through the aquiring of that same meal again. What he does acquire is not what he imagined which is past and gone, but something new and different.

In essence, then, his effort at attainment has been fruitless: he has not gained what he imagined. Having focused on the jhāna itself he overlooks its function as a steping-stone to detachment. Finding nothing in jhāna but the worldly attributes of the jhāna, being attched to those worldly attributes, he remains downbound to the world and subject to its changeability and the pain that results from that changeability.

My say.

Horner: "Lack of desire2 even for the attainment of the first meditation has been spoken of by the Lord; for whatever they imagine it to be, it is otherwise'

She does not attempt to explain.

2atammayatā This is nittaṇhatā, while tammayatā is taṇha, MA. iv. 99, Cf. M. i. 319, iii. 220, A. i. 150.

Bhikkhu Thanissaro: 'The Blessed One has spoken of non-fashioning,3 even with regard to attainment of the first jhāna, for by whatever means they construe it, it becomes otherwise from that.

3 Atammayata

Which he explains in a footnote:

"In other words, whatever the condition of the ground on which one might base a state of becoming — a sense of one's self or the world one inhabits — by the time that state of becoming has taken shape, the ground has already changed. In this case, if one tries to shape a sense of self around one's attainment of jhāna, the attainment itself has already changed."

Bhk. Bodhi/Ñanamoli [Not available on line]: "Non-identification4 (atammayatā,) even with the attainment of the first jhāna has been declared by the Blessed One; for in whatever way they conceive, the fact is ever other than that.'

4[#1066]: MA explains "non-identification" (atammayatā, lit. "not consisting of that") as the absence of craving. However, the context suggests that the absence of conceit may be the meaning. The statement "for in whatever way they conceive, the fact is ever other than that" (yena yena hi maññanti tato taṃ hoti aññathā) is a philosophical riddle appearing also at Sn 588, Sn 757, and Ud 3:10. Though MA is silent, the Udāna commentary explains it to mean that in whatever way worldly people conceive any of the five aggregates - as self or self's belonging, etc. - the thing conceived turns out to be other than the aspect ascribed to it; it is not self or self's belonging, not "I" or "mine."

Make up your own mind, but I think Bhk. Bodhi's explanation of his translation of atammayatā, as 'non-identification' is a little off track and not helpful in understanding the point. As to the rest of the comment it would better read: 'in whatever way worldly people conceive any thing (which described generally consists of the five piles: form, sense-experience, perception, own-making and consciousness) they will always be conceiving it as being permanent, belonging to self and pleasurable whereas the thing itself will always turn out to be transient, not belonging to the self and ultimately painful.

Sn V588 (Fausbøll): "In whatever manner people think (it will come to pass), different from that it becomes, so great is the disappointment (in this world); see, (such are) the terms of the world.

(Thanissaro): For however they imagine it, it always turns out other than that.

Sn V757 (Fausbøll): 34. 'Whichever way they think (it), it becomes otherwise, for it is false to him, and what is false is perishable.

(Thanissaro): Entrenched in name and form, they conceive that 'This is true.' In whatever terms they conceive it it turns into something other than that, and that's what's false about it: changing, it's deceptive by nature.

UD III.10 (Bhk. Thanissaro, trans.): "By whatever it construes [things], that's always otherwise.

As for 'maññanti' ... translating as 'imagine' is probably better than the usual: 'think' which we find most frequently in the question: "What do you think?" ~, which is just as well translated 'What do you imagine?' This way it is distinct from vitakka and vicara, and we can conceive of the second jhāna and the rest as being without 'thinking' but still having 'imagining' as the work of several of the factors of jhāna that we find nn MN 111.

[MN 114] Sevitabba-Asevitabba Suttaṃ, What Does It Lead To?

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Pāḷi Text Society Horner translation, and the Sister Upalavana translation

The Buddha delivers three discourses in brief on the subject of how to judge whether or not something should be done or used or practiced or associated with. In each case Sariputta expands the brief discussion in detail and the Buddha confirms Sariputtas analysis.

[![]() PDF ■ Read On-Line]

PDF ■ Read On-Line]

The first iteration of The Pāḷi Line c 1987. The original was typewritten. This version has been reset using Times Roman. The illustrations are from the original. Some very slight editing. Handy as a quick reference to one way of organizing the Dhamma. 74 pages.

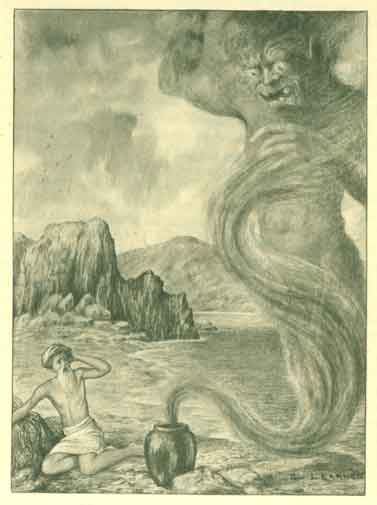

Yakka

... and when an hour of the day had gone by, lo! they herd a mighty roar and uproar in the middle of the main as though the heavens were falling upon the earth; and the sea brake with waves before them, and from it towered a black piller, which grew and grew till it rose skywards and began making for that meadow. Seeing it, they waxed fearful exceedingly and climbed to the top of the tree, which was a lofty; whence they gazed to see what might be the matter. And behold, it was a Jinni,[1] huge of height and burly of breast and bulk, broad of brow and black of blee ...

Q:15.27: "And the ginns had we created before of smokeless fire." — Palmer, 1880, S.B.E. Vol.6

Q:55.14: "And He created the ginn from smokeless fire." — Palmer, 1880, S.B.E. Vol.9

Genisis 3.5: "And Adam lived an hundred and thirty years, and begat a son in his own likeness, and after his image; and called his name Seth:" K.J.V.

![]() — p.p.

— p.p.

[1] The Arab singular (whence the French "génie"); fem. Jinniyah; the Div and Rakshah of old Guebre-land and the "Rakshasa,' or "Yaksha," of Hinduism. It would be interesting to trace the evident connection, by no means "accidental," of "Jinn" with the "Genius" who came to the Romans through the Asiatic Etruscans, and whose name I cannot derive from "gignomai" or "genitus." He was unknown to the Greeks, who has the Daimon (δαιμων, a family which separated, like the Jinn and the Genius, into two categories, the good (Agatho-dæmons) and the bad (Kako-dæmons). We know nothing concerning the status of the Jinn amongst the pre-Moslemitic or pagan Arabs: the Moslems made him a supernatural anthropoid being, created of subtile fire (Koran, chapts. xv. 27; lv.14), not of earth like man, propagating his kind, ruled by mighty kings, the last being Ján bin Ján, missionarised by Prophets and subject to death and Judgment. From the same root are "Junún" = madness (i.e., possession or obsession by the Jinn) and "Majnún" = madman. According to R. Jeremiah bin Eliazar in Psalm xli. 5, Adam was excommunicated for one hundred and thirty years, during which he begat children in his own image (Gen. v. 3) and these were Mazikeen or Shedeem - Jinns.

— The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night, Volume 1, pg 10, translated by Richard F. Burton, Printed by The Burton Club for Private Subscribers only, 1885. Image from same source.

See also SN 1.10.1, n.1

■

Yojanāni

... when lo! a damsel appeared ahead and she was in tears. The King's son asked, "Who art thou?" and she answered, "I am daughter to a King among the Kings of Hind, and I was travelling with a caravan in the desert when drowsiness overcame me, and I fell from myu beast unwittingly; whereby I am cut off from my people and sore bewildered." The Prince, hearing these words, pitied her case and, mounting her on his horse's crupper, travelled until he passed by an old ruin, when the damsel said to him, "O my master, I wish to obey a call of nature": he therefore set her down at the ruin where she delayed so long that the King's son thought that she was only wasting time; so he followed her without her knowledge and belhold, she was a Ghúlah,† a wicked Ogress, who was saying to her brood, "O my children, this day I bring you a fine fat youth for dinner;" whereto they answered, "Bring him quick to us, O our mother, that we may browse upon him our bellies full."

† The Ghúlah (fem. of Ghúl)[Ed. Goul] is the Heb. Lilith or Lills; the classical Lamia; the Hindu Yogini and Dàkini; the Chaldean Utug and Gigim (desert-demons) as opposed to the Mas (hill-demon) and Telal (who steal into towns); the Ogress of our tales and the Bala yaga [ed. Baba Yaga] of Russian folk-lore. Etymologically "Ghul" is a calamity, a panic fear; and the monster is evidently the embodied horror of the grave and the graveyard.

— Ibid, pg 54-55.

... in Gandhāra, two thousand leagues away, there stands the city of Takkasilā. If you can reach that city, in seven days you will become king there. But there is peril on the road thither, in journeying through a great forest. It is double the distance round the forest that it is to pass through it. Ogres have their dwelling therein, and ogresses make villages and houses arise by the wayside. Beneath a goodly canopy embroidered with stars overhead, their magic sets a costly couch shut in by fair curtains of wondrous dye. Arranged in celestial splendour the ogresses sit within their abodes, seducing wayfarers with honied words. 'Weary you seem,' they say; 'come hither, and eat and drink before you journey further on your way.' Those that come at their bidding are given seats and fired to lust by the charm of their wanton beauty. But scarce have they sinned, before the ogresses slay them and eat them while the warm blood is still flowing. And they ensnare men's senses; captivating the sense of beauty with utter loveliness, the ear with sweet minstrelsy, the nostrils with heavenly odours, the taste with heavenly dainties of exquisite savour, and the touch with red-cushioned couches divinely soft. But if you can subdue your senses, and be strong in your resolve not to look upon them, then on the seventh day you will become king of the city of Takkasilā."

Blee: Color, hue; complexion, visage; appearance. O.E.D.

![]() [SN 4.36.6] By Arrow Shot, M. Olds translation.

[SN 4.36.6] By Arrow Shot, M. Olds translation.

How do we reconcile 'kamma', which teaches that actions produce returning results that are hugely amplified with the law of physics that states that actions produce reactions which are equal and opposite?

By factoring in the force of the recipient's reaction or response plus the combined forces of all those that are influenced positively or negatively by the force of the actor's action on the recipient down through Time forever to the point where it is beyond notice.

We might say that if the pitcher's pitch represents the force of the action, then the force of the pitch, plus the response of the batter plus the reaction of the audience, boosters and detractors, plus the reaction of the team and the team owners, plus the reaction of the television sponsors, etc. etc. etc. down through Time represents the force returning to the pitcher. It is still in effect when some fan looks up ancient baseball statistics a thousand years later.

In this light, there is no deed, no matter how slight that is not significant. "Walk as one would walk who was with each step planting the seeds of the gold-fruit tree."

Monday, November 20, 2016

Previous upload was Monday, October 24, 2016

You don't need to leave your room.

Remain sitting at your table and listen.

Don't even listen, simply wait.

Don't even wait.

Be quiet and still and solitary.

The world will freely offer itself to you.

To be unmasked. It has no choice.

It will roll in ecstasy at your feet.

— Franz Kafka, quoted by Tom Robbins in Still Life with Woodpecker

Kafka clearly reached the point where he was able to see from the point of view of Pajapati, but at least in so far as his published work is concerned, he did not see the solution to Pajapati's problem.

![]() Dīgha Nikāya, The html formatted Pāḷi Text Society edition of the Pāḷi text ed by T.W. Rhys Davids and J.E. Carpenter.

Dīgha Nikāya, The html formatted Pāḷi Text Society edition of the Pāḷi text ed by T.W. Rhys Davids and J.E. Carpenter.

Volume 1, Suttas 1-13.

Volume 2, Suttas 14-23.

Volume 3, Suttas 24-34.

Majjhima Nikāya, The html formatted Pāḷi Text Society edition of the Pāḷi text.

Volume 1, Suttas 1-76. ed. by V. Trenckner.

Volume 2, Suttas 77-106. ed. by R. Chalmers.

Volume 3, Suttas 107-152. ed. by R. Chalmers.

Aṅguttara Nikāya, The html formatted Pāḷi Text Society edition of the Pāḷi text.

Volume 1 Ones, Twos and Threes, ed. by R. Morris, London: Pāḷi Text Society 1885, second edition, revised by A.K. Warder, 1961.

Volume 2 Fours, ed. by R. Morris, London: Pāḷi Text Society 1888, second edition 1961.

Volume 3 Fives and Sixes, ed. by E. Hardy, London: Pāḷi Text Society 1897.

Volume 4 Sevens, Eights and Nines, ed. by E. Hardy, London: Pāḷi Text Society 1899.

Volume 5 Tens and Elevens, ed. by E. Hardy, London: Pāḷi Text Society 1900.

Saṃyutta Nikāya the html formatted Pāḷi Text Society edition of the Pāḷi text.

Volume 1, Sagāthā-Vagga ed. by M. Léon Feer, London: Pāḷi Text Society 1884.

Volume 2, Nidāna-Vagga ed. by M. Léon Feer, London: Pāḷi Text Society 1888.

Volume 3, Khandha-Vagga ed. by M. Léon Feer, London: Pāḷi Text Society 1890.

Volume 4, Saḷāyatana-Vagga ed. by M. Léon Feer, London: Pāḷi Text Society 1894.

Volume 5, Mahā-Vagga ed. by M. Léon Feer, London: Pāḷi Text Society 1898.

This collection represents the unproofread, superficially reformatted files of the Dhammakaya-input Pāḷi Text Society hard copy version of the Pāḷi texts, otherwise known as 'the Goettingen files'.

With some exceptions noted below no effort has been made to proofread the 'Goettingen' files because our adaptation of the BJT Pāḷi is being read against the PTS hard copy and has in addition the advantages of being fully unabridged and formatted according to the original and organizational phrase and paragraph breaks all of which will eventually make for a much more useful version of the Pāḷi for both Dhamma researchers and Pāḷi linguists. The PTS revisions are not intended to produce a 'critical' edition, and in effect act to preserve error.

Since even re-formatting involves checking against the hard copy for certain features, here and there I have made the occasional correction.

Revised editions of some volumes were not the editions used for the original 'Goettingen' conversion but there appears to have been some secondary and incomplete revision made based on the later versions. The revised editions retain the page breaks of the original hard copy edition, and all volumes of our html formatted edition have been subjected to a certain amount of correction based on the changes suggested in the revised editions — specifically where a search-and-replace function could be easily performed across all volumes.

The 'Goettingen' files have converted what was the degree sign (°) (indicating Feer's own (that is, not found in the original Pāḷi) abridgment of some frequently used terms) into the hyphen. The problems caused in converting these back to the degree symbol are obvious. To do the job thoroughly would require a close proofreading of these files against the hard copy which is not within the scope of this posting as explained above. Some of these have been caught in passing, most are left as is. One problem that results is that occasionally a place where there were two degree signs together has further been mistaken for a single hyphenated word.

Researchers beware.

Each file represents a complete hard-copy volume. The files can be accessed from the top of the Index Page for each Nikāya volume, but the individual suttas are not linked-to from the Index pages and sutta translations are not linked to this version of the Pāḷi.

[Pages in all these files can be found or linked-to by appending "#pg000" (three digits in all cases, i.e.: 001) to the end of the url for that file. For example:

../../dhamma-vinaya/pts_pali/mn/mn.3.107-152.pts_pali.htm#pg100

brings you to page 100 of MN 3.]

These files are released under a licence which allows anyone to reproduce, modify, distribute and even sell them as long as they are properly attributed and as long as the reproduced copy is distributed under the same licence and as long as changes from the original are noted. Some of the changes listed were made in the original 'Goettingen files'. The most important of these to note is that all footnotes were removed and content straddling page breaks have had content moved back to the preceding page sometimes in units of whole phrases. The relation to the original pagination will therefore sometimes be off by several lines.

Vinaya Piṭaka, Volume 1. Mahā Vagga. Based on the edition by Hermann Oldenberg, London: Pāḷi Text Society 1879. This is an unedited, unformatted copy of the Original 'Goettingen' file. Only a header and footer have been added and tag changes were made to make the file conform to HTML 5 standards and at the request of the PTS a notice as to the license has been inserted. The remaining volumes of the Vinaya Piṭaka in the 'Goettingen' edition are from the BJT version of the Pāḷi and are therefore not included here.

Dīgha Nikāya, The Sri Lanka Buddha Jayanti Tripitaka Series Pāḷi text

Volume 1, Suttas 1-13.

Volume 2, Suttas 14-23.

Volume 3, Suttas 24-34.

Majjhima Nikāya, The Sri Lanka Buddha Jayanti Tripitaka Series Pāḷi text

Volume 1, Suttas 1-76.

Volume 2, Suttas 77-106.

Volume 3, Suttas 107-152.

Aṅguttara Nikāya, The Sri Lanka Buddha Jayanti Tripitaka Series Pāḷi text

Volume 1 Ones, Twos and Threes,

Volume 2 Fours,

Volume 3 Fives and Sixes,

Volume 4 Sevens, Eights and Nines,

Volume 5 Tens and Elevens,.

Saṃyutta Nikāya The Sri Lanka Buddha Jayanti Tripitaka Series Pāḷi text.

Volume 1, Sagāthā-Vagga

Volume 2, Nidāna-Vagga

Volume 3, Khandha-Vagga

Volume 4, Saḷāyatana-Vagga

Volume 5, Mahā-Vagga

Vinaya Piṭaka, The Sri Lanka Buddha Jayanti Tripitaka Series Pāḷi text.

Volume 1. Mahā Vagga.

Volume 2. Culla Vagga,

Volume 3. Suttavibhaṅga, Part I,

Volume 4. Suttavibhaṅga, Part II,

Volume 5. Parivāra.

These files were reproduced from those originally located on the Journal of Buddhist Ethics website. These are the files (but from the version found on Metta Net Lanka) on which the hybrid BJT/PTS version of the Pāḷi which is linked-to from all sutta translations on this site. The files here presented are the 'raw' unproofed, unedited and unformatted original files found on that site. Only the headers, footers and PTS page number references have been altered.

This version of these files appears to have had some slight proofreading done over the version I have used, and it retains footnotes (generally regarding alternative readings). The footnotes are not linked to and from their point of reference, but are indicated by number within pages and are found at the end of each page.

The page numbering, especially in the Saṃyutta Nikāya, is haphazard due especially to copy and paste errors, but also apparently from fatigue. I have done no more to straighten out the mess than to insure that there are no duplicate 'id's' which would have produced html errors.

What you need to know is that the Pāḷi text linked-to from the translations on this site has, for the most part, been proofed against the hard copy of the PTS Pāḷi. Where the sutta was not proofread it will most closely resemble the BJT version presented above.

Monday, October 24, 2016

Previous upload was Monday, September 19, 2016

![]() Vinaya Piṭaka Index Vinaya Piṭaka, Mahā Vagga and Kulla Vagga

Vinaya Piṭaka Index Vinaya Piṭaka, Mahā Vagga and Kulla Vagga

(The Sacred Books of the East translation of Vinaya Texts by T.W. Rhys Davids and Hermann Oldenberg consists of 3 Volumes, #s 13, 17, and 20. Volume 13, which contains the Patimokkha and the start of the Mahā Vagga, was previously uploaded to this site. This completes the html formatting of Volumes 17 and 20 which completes the Vinaya Texts)

This work is especially important in that it is to it that the references to the Vinaya Pitaka in the PTS translations are directed. Finding the reference to the Vinaya Texts it is then easy to locate the same chapter in the PTS Horner translation by reference to the Vinaya Index.

'Loud is the noise that ordinary men make.

Nobody thinks himself a fool, when divisions arise in the Saṅgha,

nor do they ever value another person higher than themselves.

'Bewildered are even the clever words

of him who is versed in the resources of eloquence.

As wide as they like they open their mouth.

By whom they are lead they do not see.

'"He has reviled me, he has beaten me, he has oppressed me, he has robbed me," -

in those who nurse such thoughts,

hatred will never be appeased.

'"He has reviled me, he has beaten me, he has oppressed me, he has robbed me,"-

in those who do not nurse such thoughts,

hatred is appeased.

'For not by hatred is hatred ever appeased;

by not-hatred it is appeased;

this is an eternal law.

'The others do not know

that we must keep ourselves under restraint here;

but those who know it,

their quarrels are appeased.

'They whose bones are broken by their foes,

who destroy lives,

who rob cows, horses, and treasures,

who plunder realms, -

even these may find conciliation.

How should you not find it?

'If a man find a wise friend,

a companion who lives righteously,

a constant one,

he may walk with him,

overcoming all dangers,

happy and mindful.

'If he find no wise friend,

no companion who lives righteously,

no constant one,

let him walk alone,

like a king who leaves his conquered realm behind,

like an elephant in the elephant forest.

'It is better to walk alone;

with a fool there is no companionship.

Let a man walk alone;

let him do no evil,

free from cares,

like an elephant in the elephant forest.'

VP 2. MV 10.4 - Rhys Davids/Oldenberg trans.

Monday, September 19, 2016

Previous upload was Monday, August 22, 2016

![]() The Pāḷi Line in Zipped PDF file. This is substantially the same as the on line version. Intended for printing 8-1/2 X 11 format 359 pages. For use as a workbook.

The Pāḷi Line in Zipped PDF file. This is substantially the same as the on line version. Intended for printing 8-1/2 X 11 format 359 pages. For use as a workbook.

![]() The Thera-Gāthā: Psalms of the Brethren, Mrs. Rhys Davids translation.

The Thera-Gāthā: Psalms of the Brethren, Mrs. Rhys Davids translation.

#6. Sīta-Vaniya, #7. Bhalliya, #8. Vīra, #9. Pilinda-Vaccha, #10. Puṇṇamāsa, #11. Gavaccha the Less, #12. Gavaccha the Great, #13. Vana-Vaccha, #19. Kula, #20. Ajita, #21. Nigrodha, #22. Cittaka, #23. Gosāla, #27. Lomasakangiya, #31. Gahvaratīriya, #32. Suppiya, #33. Sopāka, #34. Posiya, #42. Khadira-Vaniya, #43. Sumaṅgala, #44. Sānu, #45. Ramaṇīyavihārin, #47. Ujjaya, #48. Sañjaya, #49. Rāmaṇeyyaka, #50. Vimala, #51-54. Godhiko, Subāhu, Valliyo, Uttiyo, #55. Añjana-vaniya, #56. Kuṭivihārin (1), #57. Kuṭivihārin (2), #58. Ramaṇiyakuṭika, #59. Kosalavihārin, #71. Vacchapāla, #72. Ātuma, #73. Māṇava, #74. Suyāmana, #75. Susārada, #76. Piyañjaha, #77. Hatthāroha-Putta, #78. Meṇḍasīra, #79. Rakkhita, #80. Ugga, #81. Samitigutta, #82. Kassapa, #83. Sīha, #84. Nīta, #85. Sunāga, #86. Nāgita, #87. Paviṭṭha, #88. Ajjuna, #89. Devasabha, #90. Sāmidatta, #91. Paripuṇṇaka, #92. Vijaya, #93. Eraka, #94. Mettaji, #95. Cakkhupāla, #98. Abhaya (2), #99. Uttiya, #100. Devasabha (2), #101. Belaṭṭhakāni, #102. Setuccha, #103. Bandhura, #113. Vana-Vaccha (2), #114. Adhimutta, #115. Mahanāma, #116. Pārāpariya, #123. Valliya, #124. Gaṅgātīriya, #132. Jotidāsa, #133. Heraññakāni, #134. Somamitta, #135. Sabbamitta, #136. Mahākāḷa, #140. Sirimat, #144. 'Valliya', #145. Vitasoka, #146. Puṇṇamāsa, #147. Nandaka, #148. Bharata, #149. Bhāradvāja, #150. Kaṇhadinna, #151. Migasira, #152. Sivaka, #155. Sambula-Kaccāna, #156. Khitaka, #157. Soṇa-Poṭiriyaputta, #158. Nisabha, #159. Usabha, #160. Kappaṭa-Kura, #161. Kumāra-Kassapa, #162. Dhammapāla, #163. Brahmāli, #164. Mogharājan, #165. Visākha, Pañcālī's Son, #166. Cūḷaka, #167. Anūpama, #168. Vajjita, #172. Bākula, #173. Dhaniya, #175. Khujja-Sobhita, #176. Vāraṇa, #177. Passika, #178. Yasoja, #179. Sāṭimattiya, #180. Upāli, #181. Uttarapāla, #182. Abhibhūta, #183. Gotama (2), #184. Hārita (2), #185. Vimala (2), #186. Nāgasamāla, #190. Jambuka, #191. Senaka, #194. Candana, #197. Mudita, #198. Rājadatta, #199. Subhūta, #200. Girimānanda, #201. Sumana, #203. Kassapa of the River, #207. Yasadatta, #210. Kassapa of Uruvelā, #211. Tekicchakāri, #212. Mahā-nāga, #213. Kulla, #216. Katiyāna, #223. Sabbakāma, #224. Sundara-Samudda, #227. Sopāka (2), #227. Sarabhanga, #230. Sirimitta, #231. Panthaka Major, #232. Bhūta, #233. Kāḷudāyin, #235. Kappina the Great, #238. Upasena, Vanganta's Son, #239. Gotama, #243. Soṇa-Koḷivisa, #244. Revata, #248. Adhimutta, #249. Pārāpariya, #250. Telakāni, #257. Pārāpariya

This concludes the html formatting and uploading of The Thera-Gāthā: Psalms of the Brethren, Mrs. Rhys Davids translation.

[v. 947]

Saritvā pubbake yogī tesaṃ vatta-manussaraṃ,||

Kakiñ cā pi pacchimo kālo phuseyya amataṃ padaṃ.|| ||

Remembering the saints of other days,

And recollecting how it was they lived,

E'en though to-day be but the after-time,

He may yet win the Ambrosial Way of Peace.

THAG #257: Pārāpariya Mrs. Rhys Davids, trans.

Kāḷi itthī brahatī dhaṅka-rūpā||

Satthiṃ ca bhetvā aparaṃ ca satthiṃ,||

Bāhaṃ ca bhetvā aparaṃ ca bāhuṃ||

Sīsaṃ ca bhetvā dadhithālakaṃ' va||

Esā nisinnā abhisadda-hitvā.|| ||

Kāḷī woman huge shinny-black as crow

A thigh breaks off, and another thigh,

An arm breaks off, and another arm,

A skull breaks fashioning a bowl ere

this one sits won o'r to faith.

Saṇsāra

Saṇsāra. Saṇ = on, own, with, one's own; sarati: to go, flow, run, move along. On-flow, own-flow. Another case where the 'saṇ' would be well-served by being translated 'own'. The identification with an aspect (a living being) in the on going flow of existence.

Hunger

"We received no food. We lived on snow; it took the place of bread. The days resembled the nights, and the nights left in our souls the dregs of their darkness. The train rolled slowly, often halted for a few hours, and continued. ... There followed days and nights of traveling. ... One day when we had come to a stop, a worker took a piece of bread out of his bag and threw it into a wagon. There was a stampede. Dozens of starving men fought desperately over a few crumbs. ... A crowd of workmen and curious passersby had formed all along the train. They had undoubtedly never seen a train with this kind of cargo. Soon, pieces of bread were falling into the wagons from all sides. And the spectators observed these emaciated creatures ready to kill for a crust of bread.

A piece fell into our wagon. ... I saw, not far from me, an old man dragging himself on all fours. He had just detached himself from the struggling mob. He was holding one hand to his heart. At first I thought he had received a blow to his chest. Then I understood: he was hiding a piece of bread under his shirt. With lightning speed he pulled it out and put it to his mouth. His eyes lit up, a smile, like a grimace, illuminated his ashen face. And was immediately extinguished. A shadow had lain down beside him. And this shadow threw itself over him. Stunned by the blows, the old man was crying: "Meir, my little Meir! Don't you recognize me ... You're killing your father ... I have bread ... for you too ... for you too ..." He collapsed. But his fist was still clutching a small crust. He wanted to raise it to his mouth. But the other threw himself on him. The old man mumbled something, groaned, and died. Nobody cared. His son searched him, took the crust of bread, and began to devour it. He didn't get far. Two men had been watching him. They jumped him. Others joined in. When they withdrew there were two dead bodies next to me, the father and the son.

Elie Wiesel, Night, pg 100 ff., translated by Marion Wiesel, Hill and Wang, New York 2006. First published in French 1958 by Les Éditions de Minuit, France, as La Nuit.

![]() Saṃyutta Nikāya, Salayatana Vagga

Saṃyutta Nikāya, Salayatana Vagga

[SN 4.35.85] Empty Is the World, the Bhikkhu Bodhi translation.

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation and the F.L. Woodward translation.

Ānanda asks about the extent of what is encompassed by the idea 'Empty is the World.'

[SN 4.35.86] The Dhamma in Brief, the Bhikkhu Bodhi translation.

Linked to the Pāḷi, and the F.L. Woodward translation.

Ānanda asks for a teaching in brief. The Buddha gives him a walk to walk to begin the uprooting of thoughts about 'I am' and 'me.'

[SN 4.35.87] Channa, the Bhikkhu Bodhi translation.

Linked to the Pāḷi, and the F.L. Woodward translation.

Sariputta and Mahā Cunda visit Channa who is dying a painful death. Channa announces he will 'take the knife' (commit suicide). Sariputta questions him as to his understanding of Dhamma and Mahā Cunda recites for him a saying of the Buddha warning against the wavering that results from attachments. Later, after Channa has 'taken the knife' Sariputta questions the Buddha as to Channa's fate. The Buddha states that his was a blameless end.

[SN 4.35.88] Puṇṇa, the Bhikkhu Bodhi translation.

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation and the F.L. Woodward translation.

Punna, after being given an instruction 'in brief' by the Buddha, is questioned as to how he will deal with the fierce people of Sunaparanta where he intends to dwell. He gives a series of answers which shows he has the patience to deal with them even to the point of death.

[SN 4.35.89] Bāhiya, the Bhikkhu Bodhi translation.

Linked to the Pāḷi, and the F.L. Woodward translation.

Bahiya asks for a teaching in brief and The Buddha gives him a walk to walk to begin the uprooting of thoughts about 'I am' and 'me.'

[SN 4.35.90] Being Stirred 1 the Bhikkhu Bodhi translation.

Linked to the Pāḷi, and the F.L. Woodward translation.

The Buddha presents a method for eliminating passion which he characterizes as a sickness, a boil a being pierced by an arrow.

[SN 4.35.91] Being Stirred 2 the Bhikkhu Bodhi translation.

Linked to the Pāḷi, and the F.L. Woodward translation.

The Buddha presents a method for eliminating passion which he characterizes as a sickness, a boil a being pierced by an arrow.

[SN 4.35.92] The Dyad 1 the Bhikkhu Bodhi translation.

Linked to the Pāḷi, the M. Olds translation and the F.L. Woodward translation.

The Buddha describes the ultimate duality and states that no one could reject this duality and point out another duality.

[SN 4.35.93] The Dyad 2, the Bhikkhu Bodhi translation.

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation the M. Olds translation and the F.L. Woodward translation.

The Buddha explains that it is a consequence of the meeting of a sense organ and a sense object that sense-consciousness, sense-contact, sense-experience, feeling, and self-awareness appear and that each of these individual elements being changeable, the resulting consciousness is changeable.

[SN 4.35.94] Untamed, Unguarded, the Bhikkhu Bodhi translation.

Linked to the Pāḷi, the M. Olds translation and the F.L. Woodward translation.

The Buddha teaches that united with the six spheres of touch is the experience of pain or pleasure in accordance with whether or not the senses have been tamed, trained and are well guarded or not.

[SN 4.35.95] Māluṅkyaputta, the Bhikkhu Bodhi translation.

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation and the F.L. Woodward translation.

The Buddha gives Malankaya-Putta a teaching in brief which inspires him to attain arahantship.

[SN 4.35.97] Dwelling in Heedlessness, the Bhikkhu Bodhi translation.

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation, the M. Olds translation and the F.L. Woodward translation.

The Buddha defines living dangerously as living with the forces of the senses uncontrolled. Living carefully is defined as living with the sense-forces controlled.

[SN 4.35.98] Restraint, the Bhikkhu Bodhi translation.

Linked to the Pāḷi, and the F.L. Woodward translation.

The Buddha describes restraint and lack of restraint in terms of whether or not one indulges and hangs on to the six senses.

[SN 4.35.99] Concentration, the Bhikkhu Bodhi translation.

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation and the F.L. Woodward translation.

The Buddha urges the Bhikkhus to develop serenity (samādhi) in order to see things as they are.

[SN 4.35.100] Seclusion, the Bhikkhu Bodhi translation.

Linked to the Pāḷi, and the F.L. Woodward translation.

The Buddha urges the Bhikkhus to develop solitude in order to see things as they are.

[SN 4.35.101] Not Yours 1, the Bhikkhu Bodhi translation.

Linked to the Pāḷi, the Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation and the F.L. Woodward translation.

The Buddha urges the bhikkhus to let go of experience through the senses. He compares their nature as not belonging to the self to the nature of the twigs and branches of the Jeta Grove.

[SN 4.35.102] Not Yours 2, the Bhikkhu Bodhi translation.