Index of the Suttas of the

Aṅguttara Nikāya

Dasaka-Nipāta

Aṅguttara Nikāya

PTS: Aṅguttara Nikāya, The html formatted Pāḷi Text Society edition of the Pāḷi text.

Volume IV Tens and Elevens, ed. by E. Hardy, London: Pāḷi Text Society 1900.

BJT: Aṅguttara Nikāya, The Sri Lanka Buddha Jayanti Tripitaka Series Pāḷi text.

Volume IV Tens and Elevens.

The Pāḷi text for individual suttas listed below is adapted from the Sri Lanka Buddha Jayanti Tripitaka Series [BJT]. Pāḷi vagga titles are links to this version of the Pāḷi. Both the Pāḷi and the English have been completely unabridged — there are no '... pe ...' or '...'s. In the sections discussing preeminent individuals, the name of the individual is a link to biographical material.

Each translation is linked to its Pāḷi version and to the PTS, Olds and where available to the ATI Bhk. Thanissaro and WP Bhk. Bodhi translations, and each of these is in turn linked back to each of the others. The Pāḷi has been checked against the Pāḷi Text Society edition, and many of the suttas have been reformatted to include the original Pāḷi (and/or organizational) phrase and sentence breaks.

PTS: The Book of the Gradual Sayings or More-Numbered Suttas

ATI: Translations of bhikkhu Thanissaro and others originally located on Access to Insight

WP: The Numerical Discourses of the Buddha, bhikkhu Bodhi translation

BD: The M. Olds translations. [PDF]

10. Dasaka Nipāta V.1

PTS: The Book of the Tens

ATI: Book of the Tens

WP: The Book of the Tens

I. Ānisaṃsa-Vagga, V.

PTS: Profit, V.1

WP: Benefits, 1339

In a paṭicca samuppāda-like sutta the Buddha explains how skillful ethical behavior leads directly to knowing and seeing freedom.

Discussion (Suttas 1-3)

PTS: What is the object?, V.1

BD: What's the Point? Olds, trans.

WP: What Purpose? 1339

#2. Ceta-nākaraṇīya Suttaṃ, V.2

The Buddha explains why when one has established perfect ethical conduct there is no need to make an effort of will to bring forth freedom from regret, joy, enthusiasm, calm, happiness, serenity, knowing and seeing things as they are, disgust with things as they are, and knowing and seeing freedom, for these things arise naturally as a consequence of perfect ethical conduct.

PTS: Thinking with Intention, V.3

WP: Volition, 1340

#3. Paṭhama Upanisa Suttaṃ, V.4

The Buddha explains, in a paṭicca-samuppāda-like sutta, how each step from ethical conduct to freedom from regret, joy, enthusiasm, calm, happiness, serenity, knowing and seeing things as they are, disgust with things as they are, and knowing and seeing freedom depends on the previous condition.

PTS: Basis a (by the Teacher), V.4

WP: Virtuous Behavior, 1341

#4. Dutiya Upanisa Suttaṃ, V.5

Sariputta explains, in a paṭicca-samuppāda-like sutta, how each step from ethical conduct to freedom from regret, joy, entheusiasm, calm, happiness, serenity, knowing and seeing things as they are, disgust with things as they are, and knowing and seeing freedom depends on the previous condition.

PTS: Basis b (by Sariputta), V.6

WP: Proximate Cause, 1343

#5. Tatiya Upanisa Suttaṃ, V.6

Ānanda explains, in a paṭicca-samuppāda-like sutta, how each step from ethical conduct to freedom from regret, joy, entheusiasm, calm, happiness, serenity, knowing and seeing things as they are, disgust with things as they are, and knowing and seeing freedom depends on the previous condition.

PTS: Basis c (by Ānanda), V.6

WP: Ānanda, 1343

#6. Samādhi Suttaṃ, V.7

In response to a question by Ānanda, the Buddha confirms that there is perception beyond existence.

This and the next are two very important suttas!

PTS: Concentration a (by the Teacher), V.6

ATI: Concentration Thanissaro Bhikkhu, trans.

BD: Serenity, Olds, trans.

WP: Concentration, 1343

#7. Samādhi Suttaṃ, V.8

In response to a question by Ānanda, Sariputta confirms that there is perception beyond existence.

PTS: Concentration b (by Sariputta), V.7

ATI: With Sariputta Thanissaro Bhikkhu, trans.

WP: Sāriputta, 1344

BD: Serenity, by Sāriputta, Olds, trans.

#8: Saddha Suttaṃ, V.10

Covering #s 8,9, and 10. Three suttas which describe a stepwise method of progression from faith to arahantship. Each slightly different. Since each purports to be a path to Arahantship an equivalence is implied. Your homework is to see if you can see the equivalence. Another challenge is to rationalize the fact that here one sacred cow is left out, there another. For example the Eightfold Path is omitted in all but one of these methods, the jhānas are included in only one. The trick is to let go of any tendency to hang on unyieldingly to terminology while simultaneously being so precise in one's thinking that nothing essential to the process is missing.

The Pāḷi is abridged in a way which allows for multiple versions of the missing sections. The BJT has a briefer version than the one used here. The Woodward expansion is based on the more verbose version (based on his suggestion in a footnote).

A stepwise method of progression from faith to arahantship.

PTS: The Believer, V.8

WP: Faith, 1345

#9: Santa-Vimokkha Suttaṃ, V.11

A stepwise method of progression from faith to arahantship.

PTS: The Blissful, V.9

WP: Peaceful, 1346

#10: Vijjā Suttaṃ, V.12

A stepwise method of progression from faith to arahantship.

PTS: By knowing, V.9

WP: True Knowledge, 1347

II. Nātha-Vagga, V.15

PTS: Things Making for Warding, V.10

WP: Protector, 1348

#11: Senāsana Suttaṃ, V.15

The Buddha describes five factors in the individual and five factors in his lodging that conduce to rapidly attaining Arahantship.

PTS: Lodging, V.10

WP: Lodging, 1348

#12: Pañcaṅga Suttaṃ, V.16

Five things to give up and five to develop to be called one who is completely proficient.

PTS: Factors, V.12

WP: Five Factors, 1349

#13: Saṃyojana Suttaṃ, V.17

The Buddha names the ten things which 'yoke' individuals to rebirth [samyojana]; five yoking the individual to every possible sort of rebirth including those as an animal, monster, ghost or resident in Hell, but also to this and higher re-births and five yoking one to rebirths in higher realms even though one may have seen through the first five. Relates intimately to the conditions necessary to be called a Streamwinner (having seen through the first three of the first five) and to being a Non-returner (having warn down or eliminated most of the last five).

PTS: Fetters, V.13

ATI: Fetters

WP: Fetters, 1350

#14: Ceto-khila Suttaṃ, V.17

Five obstructions of the heart that if not abandoned, and five things that twist up the heart that if not uprooted, signal decline in a seeker, but which if abandoned and uprooted signal progress.

PTS: Obstruction, V.13

WP: Mental Barrenness, 1350

#15: Appamāda Suttaṃ, V.21

Ten similes extolling the virtues of not being careless (appamāda).

The term to understand here is 'appamāda': a = non; pamāda = carelessness. One of the most frequently occurring concepts in the whole of the Pāḷi Cannon. This word is a mantra. A magical word which if concentrated upon, repeatedly pronounced to the point where it induces a hypnotic trance, opens up to reveal the memory embedded in its creation. A memory which goes far beyond the admittedly valuable idea of not being carelesss.

PTS: Seriousness, V.16

ATI: Heedfulness

BD: Appamāda, Olds, trans.

WP: Heedfulness, 1354

#16: Āhuneyya Suttaṃ, V.23

Ten individuals considered worthy to receive offerings, gifts, signs of respect and who are a peerless opportunity for making good kamma.

PTS: Worshipful, V.17

WP: Worthy of Gifts, 1355

#17: Paṭhama Nātha-karaṇa Suttaṃ, V.23

Ten things that are protections for the seeker.

PTS: Warder a, V.18

ATI: Protectors

WP: Protector (1), 1355

#18: Dutiya Nātha-karaṇa Suttaṃ, V.25

Ten things that are protections for the seeker with the additional protection that having these protections the bhikkhus are inclined to instruct and guide such a seeker.

PTS: Warder b, V.20

WP: Protector (2), 1356

ATI/DTO: Protectors (2), Bhk. Thanissaro trans.

#19: Paṭhama Āriya-vāsa Suttaṃ, V.29

A list (in brief) of ten ways in which the Aristocrat (here equal to the Arahant) abides.

PTS: Ariyan Living a, V.21

WP: Abodes of the Noble Ones (1), 1359

#20: Dutiya Ariya-vāsa Suttaṃ, V.29

A list (in some detail) of ten ways in which the Aristocrat (here equal to the Arahant) abides. There is a strange order of terms here and in the previous sutta, maybe a mistake. Not very important. In the beginning and end both suttas have 'abided, abides, and will abide', (āvasiṃsu, āvasanti, āvasissanti) but just before the end in this sutta is the standard order: 'in the past abided, in the future will abide, and in the present abides'.

PTS: Ariyan living b, V.21

ATI: Dwellings of the Noble Ones Thanissaro Bhikkhu, trans.

WP: Abodes of the Noble Ones (2), 1359

III. Mahā-Vagga, V.32

PTS: The Great Chapter, V.23

WP: The Great Chapter, 1362

#21: Sīhanāda Suttaṃ, V.32

A list of the ten powers of the Buddha that qualify him to set rolling the Wheel of Dhamma. Compare with SN 5.52.11-24 where these are powers claimed by Anuruddha, the bhikkhu famed for clairvoyance.

PTS: The Lion, V.23

WP: The Lion, 1362

#22: Adhi-vutti-pada Suttaṃ, V.36

The Buddha makes a bold statement about his knowledge and right to turn the Wheel of Dhamma. He then gives a list of the 10 Powers of a Buddha.

PTS: Statements of doctrine, V.26

WP: Doctrinal Principles, 1364

#23: Kāya Suttaṃ, V.39

A categorization by bodily control, control of speech, or by application of wisdom upon seeing them of things which need to be abandoned.

PTS: With body, V.26

WP: Body, 1365

#24: Mahā Cunda Suttaṃ, V.41

Cunda spins a twist on a list of things which upon seeing them need to be abandoned such that he is able to rightfully say he knows Dhamma and has developed bodily control, virtue, heart and wisdom.

The abridgment, which was followed by Woodward, Bhk. Thanissaro and Bhk. Bodhi is in a confused state. It is given as

I, a.b.c...z, II,a,III,b,z;

and should at least have been:

I, a,b,c....z; II, a,b.c....z III, a.b.c....z;

but, I believe it should properly be:

A,i,ii,iii; B,i,ii,iii. ...Z

I have followed the latter in the unabridgement of both the Pāḷi and Woodward's translation.

PTS: Cunda the Great, V.28

ATI: Cunda

WP: Cunda, 1367

#25: Kasiṇa Suttaṃ, V.46

Enumeration of ten devices used to assist in the development of concentration. My translation puts this series in an entirely new light ... or rather brings them into the light so that those with eyes in their heads that can see can see the object.

PTS: The devices, V.31

BD: Kasiṇa, Olds translation

WP: Kasiṇas, 1370

#26: Kālī Suttaṃ, V.46

Maha Kaccana explains to Kali the meaning of one of the Buddha's brief sayings: Understanding the limitations of the devices used for the development of concentration, one does not form attachment to them and by extension one does not form attachment to anything or anyone and by that one is free.

PTS: Kali, V.31

WP: Kāḷī, 1370

#27: Mahā-Pañha Suttaṃ, V.48

Some bhikkhus are asked that since both they and the Buddha teach a goal of understanding all things, what is the difference between the two systems. The Buddha tells the bhikkhus that when this question is asked the response should be: 'The 10 Questions' (Giving them in full as found in this sutta).

This is a subtle response to this question in that The 10 Questions is a broad and deep exposition to the 10th power of how everything in the world is to be let go. Each of 'the 10' is a complete path to utter detachment seen from a different perspective. A sutta no serious student of the Dhamma should neglect! For more on this subject see the footnotes to Woodward's translation, the next sutta, and The Pāḷi Line.

PTS: The Great Questions a, V. 33

WP: Great Questions (1), 1371

In an alternate version of the Great 10 Questions, the Kajaṅgala bhikkhunī expands the questions given in brief to a group of lay followers. Her version contains a few answers that differ from those given in the previous sutta [AN 10 27]. This is the set of ten questions on which much of The Pāḷi Line (the introductory course in the Buddhism of the Pāḷi Suttas recommended here) is based. These ten questions can be used in much the same way as the kasina, or concentration device, as a 'theme' of practice. In each individual case it is explicitly stated that thorough comprehension leads to 'the end of dukkha' or Arahantship. The actual experience is that one sees how each of these is of such a nature as to encompass all the rest ... and all the other doctrines of the system.

It is important to note that there are several versions of the ten questions. They are all equally valid in terms of their scope and use. Numerous other sets could be constructed by reviewing the whole of the Aṅguttara Nikāya.

PTS: The Great Questions b, V.36

WP: Great Questions (2), 1376

#29: Paṭhama Kosala Suttaṃ, V.59

The Buddha describes how even the most enduring of phenomena and the most lofty of doctrines are burdened with change and should be regarded with revulsion; he then declares of certain doctrines that if their goals are attained they will provide refuge. See If Not "Mine" for some discussion as to the difficulties translators have had with the little ditty found in this and other suttas.

'If there were

no I

There would be no

My

Not becoming

Me

There will be

no becoming

My'

PTS: The Kosalan a, V.40

ATI: The Kosalan Thanissaro Bhikkhu, trans.

WP: Kosala (1), 1379

BD: Set-backs and Reversals, Olds, trans.

#30: Dutiya Kosala Suttaṃ, V.65

Raja Pasenadi pays a visit to the Buddha and shows great respect and enumerates the reasons for his great respect. Woodward notes that this sutta contains statements that would not likely have been known to Raja Pasenadi. This seems an obvious case of tampering by early compilers. Compare this sutta with MN 89 Horner (the much more likely true story). The issue for us is: does it matter? As far as the doctrines contained in the sutta they have no inconsistency with their counterparts in the rest of the Suttas (they are in fact mostly verbatim pick-ups). It is distasteful to our sensibilities that the editors should make an explicit claim that this was a true sutta when the fact is insupportable, but the reality is that story telling tradition has always been very liberal in such matters ... right on up to today. In any case, what we should not do is 'throw the baby out with the bath water' and disregard the Dhamma within the sutta as not-dhamma because of a liberty taken by an editor.

PTS: The Kosalan b, V.46

WP: Kosala (2), 1383

IV. Upāli-Vagga, V.70

PTS: Upali and Ānanda, V.50

WP: Upāli, 1387

#31: Upāli Suttaṃ, V.70

Upāli asks the Buddha about the reasons for establishing the Patimokkha (the rules of the Order) and about the various reasons for its suspension. The Buddha tells Upali of the ten things that are taken into consideration before he formulates a rule for the order. Bhk. Bodhi has the second part of this sutta incorporated into the next sutta.

PTS: Upali and the Obligation, V.50

WP: Upāli, 1387

WP: 32. Suspending, 1387

#32: Ubbāhikā Suttaṃ, V.71

Upali asks the Buddha about the qualifications needed for a bhikkhu to be a member of a council concerned with expulsion of a bhikkhu.

PTS: Passing sentence, V.51

WP: 33. Adjudication, 1387

#33: Upasampadā Suttaṃ, V.72

Upali asks the Buddha about the qualifications needed for a bhikkhu to give full ordination.

PTS: Full ordination, V.52

WP: 34. Full Ordination, 1388

#34: Nisasaya Suttaṃ, V.73

Upali asks the Buddha about the qualifications needed for a bhikkhu to assign tutelage and to be provided with a novice attendant. The BJT Pāḷi and the Pāḷi used by Bhk. Bodhi have this as two suttas which would make more sense as these are two separate topics. As it is Woodward has possibly been confused by putting them together and has a mixed message in his translation as to whether or not the second part has to do with taking care of a novice or being assigned a novice. In the first case the two suttas would fit together, in the latter, not. A good case for not abridging.

PTS: Tutelage, V.52

WP: 35. Dependence, 1389

WP: 36. Novice, 1389

#35: Saṅgha-bheda Suttaṃ, V.73

Upali asks the Buddha about the meaning of the expression: breaking up (creating a schism in) the Order.

PTS: Schism in the Order a, V.53

WP: 37. Schism (1), 1389

#36: Saṅgha-sāmaggi Suttaṃ, V.74

Upali asks the Buddha about the meaning of the expression: Harmony in the the Order.

PTS: Harmony in the Order a, V.53

WP: 38. Schism (2), 1390

#37: Paṭhama Ānanda Saṅgha-bheda Suttaṃ, V.75

Ānanda asks the Buddha about the meaning of the expression: breaking up (creating a schism in) the Order.

PTS: Schism in the Order b, V.54

WP: 39. Ānanda (1), (incorporates the next sutta) 1390

#38: Dutiya Ānanda Saṅgha-bheda Suttaṃ, V.75 [BJT incorporates in the previous sutta]

Ānanda asks the Buddha about the results of causing the breaking up (creating a schism in) of the Order and the fruit of such.

PTS: Fruits of causing schism, V.54

#39: Paṭhama Ānanda Saṅgha-sāmaggi Suttaṃ, V.76

Ānanda asks the Buddha about the meaning of the expression: 'Harmony in the Order'.

PTS: Harmony in the Order b, V.54

WP: 40. Ānanda (2), (incorporates the next sutta) 1390

#40: Dutiya Ānanda Saṅgha-sāmaggi Suttaṃ, V.76 [BJT incorporates in the previous sutta]

Ānanda asks the Buddha about the consequences of fostering harmony in the Order and the fruit of such.

PTS: Fruits of causing harmony in the Order, V.54

V. Akkosa-Vagga, V.77

PTS: Reviling, V.55

WP: Insults, 1390

#41: Vivāda Suttaṃ, V.77

Upāli asks the Buddha about the reasons quarrels arise in the Order.

PTS: Quarrels, V.54

WP: Disputes, 1391

#42: Paṭhama Vivāda-mūla Suttaṃ, V.78

Upāli asks the Buddha about the roots of quarrels.

PTS 42: Roots of quarrels a, V.55

WP: Roots (1), 1392

#43: Dutiya Vivāda-mūla Suttaṃ, V.78

Upāli asks the Buddha about the roots of quarrels.

PTS 43: Roots of quarrels b, V.55

WP: Roots (2), 1392

#44: Kusinārā Suttaṃ, V.79

The Buddha cautions those who are eager to criticize others that they should first examine themselves as to their competency to do so and then to set up within themselves the discipline to speak only in a timely manner, according to fact, gently, well said such as to inspire and profit, and with a friendly heart.

PTS: At Kusinara, V.55

WP: Kusinārā, 1392

#45: Rāj'antepura-p-Pavesana Suttaṃ, V.81

Ten dangers attending upon a bhikkhu who would habituate the court's of kings. Just a couple of the things one should think about when contemplating fame, favors and flattery.

The First Danger

of habituating the Kings Court

... suppose the king is seated with Wife #1 and here comes some beggar who habituates the king's court.

Wife #1, on seeing him, smiles,

or else he, on seeing her, smiles.

Then the king thinks ...

— adapted from AN 10.45

PTS: Entering the royal court, V.57

WP: Entering, 1394

#46: Sakya Suttaṃ, V.83

The Buddha admonishes the Sakkyans to keep the Uposatha day in all its eight parts. This is a hypnotic magic charm. To ignore or abbreviate the series of numbers running up and down is to miss virtually the entire point. Without this feature the whole thing could have been done in one sentence, so one must ask why it was done in this 'tedious' way. Anyone familiar with inducing hypnosis will recognize what is being done here immediately ... unless it is obscured by abridgment. As a secondary mater, both for the Sakkyans then and for the modern reader interested in learning Pāḷi, this was/is a good sutta to study in the Pāḷi to learn to count. Also, and not incidentally, the sutta is great encouragement for those concerned about avoiding hell and securing a foothold in progress in the system.

PTS: Sakyans, V.59

ATI: To the Sakyans (on the Uposatha)

WP: Sakyans, 1395

#47: Mahāli Suttaṃ, V.86

Mahāli asks the Buddha about the reasons for bad and good deeds. In a very interesting post-script to the direct answer that it is as a consequence of lust, hatred, delusion, not noticing the beginnings of things, and following wrong views and the reverse of these five, he further states that without these ten things there would be no wrong or deviant living or right or straight living. In other words these things amount to the sum total of what is needed to be done in the system to attain its goals. No mention of the Magga. In other words, the Magga is a method for eliminating the first five of these things, so instruction can be given in these two general ways: either by stating the things to be eliminated or by stating the method to eliminate them. The choice, presumably being made based on the listener's inclination and capabilities. Once a request was made for an instruction in brief where the response simply stated: "Whatsoever has to do with hunger/thirst (taṇhā), know that is not Dhamma."

PTS: Mahali, V.61

WP: Mahāli, 1398

#48: Dasa-Dhamma Suttaṃ, V.87

Ten Dhammas that should be kept in mind by a bhikkhu. Good things for one and all to keep in mind, but of special importance to a bhikkhu, for the fall for one who has joined the order and is therefore representative of the Buddha and the Dhamma is much more serious. For bhikkhus this should be a hair-raising sutta. A good sutta for comparing translations.

PTS: Conditions, V.62

ATI: Ten Things, Bhk. Thanissaro, trans.

Discourse on the Ten Dhammas, Piyadassi Thera, trans.

BD: Ten Things, Olds, trans.

WP: Things, 1398

#49: Sarīra-ṭ-ṭha-Dhamma Suttaṃ, V.88

The Buddha points out 10 things that are bound up in existing in a body.

PTS: Inherent in body, V.63

BD: Things of this Bone-Supported Corpse, Olds translation,

WP: Subsisting through the Body, 1399

#50: Bhaṇḍana Suttaṃ, V.88

The Buddha instructs a number of bhikkhus who were engaged in bandying words about in unfriendly banter, as to ten things which make for friendly relations and living in unity, saying that living in discord was unworthy of those who had left home for the homeless life.

PTS: Strife, V.63

WP: Arguments, 1399

VI. Sa-citta-Vagga, V.92

PTS: One's Own Thoughts, V.66

WP: One's Own Mind, 1402

#51: Sa-citta Suttaṃ, V.92

The Buddha admonishes the bhikkhus to examine themselves for faults and then to make a strong effort to get rid of any faults found; this as a key to the comprehension of their hearts.

PTS: One's own heart a, (By the Master), V.66

ATI: One's Own Mind

WP: One's Own Mind, 1402

#52: Sāriputta Suttaṃ, V.94

Sariputta admonishes the bhikkhus to examine themselves for faults and then to make a strong effort to get rid of any faults found; this as a key to the comprehension of their hearts. Although this sutta begins with the idea that though one may not be able to read the hearts of others, one should be able to read one's own heart, what is not said here is that this is the very method for learning to read the hearts of others.

PTS: One's own heart b, (By Sariputta), V.67

WP: Sāriputta, 1403

#53: Ṭhiti Suttaṃ, V.96

The Buddha spurs on the bhikkhus warning them not only to guard against backsliding but also against accepting the status quo, admonishing the bhikkhus to examine themselves for faults and then to make a strong effort to get rid of any faults found; this as a key to the comprehension of their hearts. (Ending as with the two previous suttas). It is interesting that here he is speaking of a person who has faith, virtue, much knowledge, the habit of casting off things, wisdom and quick wits. One might think this was pretty good, but the warning is not to be complacent even with relatively high accomplishments. This is a monster of a mountain that must be climbed!

PTS: Standing Still, V.67

WP: Standstill, 1403

#54: Samatha Suttaṃ, V.98

The Buddha gives two criteria for evaluating the knowledge of one's own heart: attainment of higher wisdom and insight into Dhamma, and calm of heart; and then he gives a method for judging the right course to take with regard to clothing, food, location and persons.

This is an invaluable sutta with regard to day-to-day practice.

Bhk. Bodhi has translated 'Samatha' as 'serenity'; Woodward uses 'peace'; Bhk. Thanissaro uses 'tranquility. 'Samatha' is a term that both encompasses and is subordinate to 'samādhi'. It stands for the general goal of the calm necessary for unbiased vision of things the way they really are, and it is the practice of stilling, calming and tranquilizing the body in preparation for samādhi. What is required for this word then, is one that implies the general idea of calm (applicable to both body and mind, or as here, heart), plus the specific idea of calm of body. 'Serenity' is more of a mental quality. It is the idea of being calmly above it all. Therefore I suggest that for 'samatha' we use 'calm' or 'tranquility'; and reserve 'serenity' for 'samādhi.'

PTS: Peace of heart, V.68

ATI: With Regard to Tranquility, Bhk. Thanissaro, trans.

WP: Serenity, 1404

#55: Parihāna Suttaṃ, V.102

Sariputta explains the meaning in Gotama's system of the expressions: 'Of a nature to wane', and 'Of a nature not to wane'. If a person doesn't listen, forgets what he has heard, teachings formerly memorized are not rehearsed, and he has no intuitive understanding he tends to wane; if he listens, remembers what he has heard, rehearses formerly memorized teachings, and cultivates intuitive knowledge he tends not to wane.

PTS: Waning, V.70

WP: Decline, 1407

#56: Paṭhama Saññā Suttaṃ, V.105

The Buddha reveals ten perceptions which are very helpful to seekers. I did a translation of this sutta so that we would have here a contrast with Woodward's translation. There is an enormous difference when 'saññā' is translated 'perception' rather than 'idea'. Saññā = 'one-knowing' or 'first-knowing' or 'once-knowing' = perception, not idea. The difference is that an idea is an abstract thing, tending to suggest an intellectual understanding apart from the perception of it being something connected to the self (speaking conventionally, or, rather, since these things are 'helps along the way', speaking with regard to the identification with 'this being'); here the idea is to have actually seen these things as they manifest themselves to one's self ... actually seeing, or smelling, or tasting the identical repulsion one has of excrementia, in some otherwise delightful food for example, or the actual feeling of weariness when some ambition arises, or the conscious recognition of release (a deep sigh of relief that feels like it is the first full breath one has had in a long time ... which it is) when one has finally passed the withdrawal stage connected with some habitual practice one has let go.

PTS: Ideas a, V.71

BD: Perceptions, Olds, trans.

WP: Perceptions (1), 1409

#57: Dutiya Saññā Suttaṃ, V.106

The Buddha reveals ten perceptions which are very helpful to seekers.

This sutta while including some of the perceptions from the previous sutta, adds a few that are in need of a little explanation. Perception of bones, larva, mal-coloration, swelling. These ideas are generally associated in the commentaries with the use of concentration devices (specifically those of observing a corpse). That has the tendency to create the same distance from them as does the use of 'idea' in the translation. These are 'live' perceptions. One sees in one's mind's eye, as clearly as in a vivid dream, maggots heaving around, as often as not within 'one's own' or some live person's body, or one sees all mankind as a mess of maggots roiling around in some open wound, not just in the body of a corpse one is using as a concentration device. One sees a repulsive swelling or bruising in ordinary objects and people, or one sees ordinary objects and people as just a repulsive swelling. Again, in the mind's eye, one perceives this whole universe as a disgusting skeleton, or one sees right into the bones of some person or sees some person as simply a walking skeleton. Woodward does not comment, Bhk. Bodhi has these as perceptions of corpses. The Pāḷi has these as stand-alone concepts; not connected to corpses. The distinction points out the utility: the kasina (observing a corpse) is used to stimulate the perception. The end result is not the perception of these things in a corpse, but the application of the perception of these things to everyday experience, they serve to make one aware on a gut level of the reality of things. One uses the recollection of these perceptions to counter lust or other disadvantageous feelings that have arisen. They instill sobriety.

PTS: Ideas b, V.72

BD: Perceptions 2, Olds, trans.

WP: Perceptions (2), 1409

#58: Mūla Sutta, V.106

The Buddha teaches ten important ideas by posing them as questions that might be asked of Buddhists by outsiders. There is an interesting manipulation of the term 'dhamma' here which illustrates its dual meaning as 'thing' and 'Form' (in the sense of 'Good Form') or 'The Teaching.' This translation of 'Dhamma' as 'Good Form' comes from the discussion of the term in Rhys David's Buddhist India pg 292 where he points to the etymological root as "identical with the Latin forma" our 'form'. This serves very well for this word where it must stand for 'thing' and is a synonym for 'rūpa' (often translated 'form') in this sense, and also for 'the best way to do a thing', or 'Good Form'. This use for 'form' is found in Asian cultures where the idea is exactly that there is a perfectly correct and efficient way to do even the smallest things. The expression 'Doing Forms' is also used as the English translation for the term in Asian martial arts that stands for various groups of moves in practice routines. At this time the word 'Dhamma' for Gotama's teaching is relatively well known here and it will probably stick, but there is confusion that results when the word must be used for 'things' and ... 'Good form' in general.

PTS: Rooted in the Exalted One, V.72

ATI: Rooted, Thanissaro Bhikkhu, trans.

BD: The Root

WP: Roots, 1410

#59: Pabbajjā Suttaṃ, V.107

The Buddha gives the bhikkhus 10 things to aim at in their training.

PTS: Forthgoing, V.73

WP: Going Forth, 1410

ATI: Gone Forth, Thanissaro Bhikkhu, trans.

#60: Giri-m-ānanda Suttaṃ, V.108

The Buddha gives definitions for 'The Ten Perceptions': The idea of discontinuity, of not-self, of the foul, of disadvantages, letting go, dispassion, ending, weariness, of discontinuity in the own-made, of recollection of respiration. In this sutta is a case of 'curing' by way of hearing the Dhamma. Also in this sutta is found a version of what would later become the satipaṭṭhana method.

In this sutta Bhk. Bodhi translates 'saṅkhāra' both as 'conditioned phenomena' and as 'activities'. The first is simply incorrect (all own-made phenomena are impermanent, but not all conditioned phenomena are impermanent: Nibbāna is conditioned), the second is one-sided and too narrow, the two together are confusing. For the issues raised by the mistranslation of this term see the article: 'Is Nibbāna Conditioned?'

PTS: Giri-m-ānanda, V.74

ATI: To Girim-Ānanda, Piyadassi Thera, trans.

ATI: To Girim-Ānanda, Thanissaro Bhikkhu, trans.

WP: Giri-m-ānanda, 1411

VII. Yamaka-Vagga, V.113

PTS: The Pairs, V.78

WP: Pairs, 1415

#61: A-vijjā Suttaṃ, V.113

In the technique of the paṭicca samuppāda, the Buddha traces out how blindness rolls on and the way freedom from it is managed. The distinction in the terms used here from those used in the paṭicca samuppāda should be enlightening. The term for the relationship between a thing and its result is 'food'. This is the food of that. The significant difference between the idea of 'food' and the idea of 'cause' should be kept in mind when thinking about the meaning of this sutta and the translation of terms such as 'paccaya'.

PTS: Ignorance, V.78

WP: Ignorance, 1415

ATI: Ignorance, Bhk. Thanissaro, trans.

#62: Taṇhā Suttaṃ, V.116

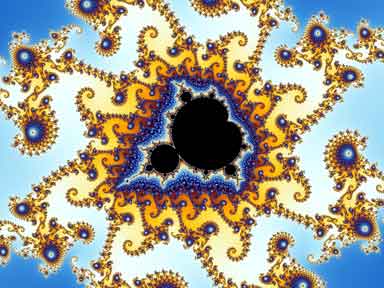

Mandelbrot Set. The set of complex numbers for which the function does not diverge when iterated from, i.e., for which the sequence, etc., remains bounded in absolute value. Wikipedia. Google for hundreds of beautiful images.

![]() — p.p.

— p.p.

In the technique of the paṭicca samuppāda, the Buddha traces out how hunger to exist rolls on through blindness and the way freedom from it is managed. Almost identical with the previous sutta, but beginning with thirst for existence (Woodward's 'craving-to-become').

Together these bracket the first condition of the paṭicca samuppāda: Avijjā paccayo saṅkhārā. [see for example SN2.12.001] Blindness (Woodward's 'Ignorance') results in own-making. On one side it answers the question: 'then what is it that results in blindness?' And on the other side it answers the question as to why blindness results in own-making.

Another thing is that since 'taṇhā,' thirst, (Woodward's 'craving'), results in the usual first condition of the paṭicca samuppāda, 'blindness', and is also a 'condition' following sense experience within the formula, we can see by this that the paṭicca samuppāda is to be taken as a series of what Bhk. Thanissaro has called 'feedback loops' and should not be taken exclusively as a direct-line analysis. An interesting comparison could be made to the Mandelbrot Set, where, at any point along a series a new series could be begun, and so on without end.

PTS: Craving, V.80

WP: Craving, 1418

#63: Ni-ṭ-ṭhaṇ-gata Suttaṃ, V.119

Gotama states that all those who attain the goal are possessed of or certain about 'view'; some of those reaching the goal here in the human state and some of them reaching the goal after 'departure'. 'View' here would be the 'Dhamma Eye': "all things that have come into existence are destined to come to an end," or one form or another of the Four Truths.

PTS: The goal, V.81

BD: Taking A Stand, Olds, trans.

WP: Certainty, 1419

#64: Avecca-p-pasanna Suttaṃ, V.120

Almost identical to the previous sutta except that here Gotama asserts that all those who have unwavering faith in him are Streamwinners. Something to consider for those insisting that there can be no stream-entry without breaking the first three samyojanas. The catch is of course the 'unwavering' part. It is an easy thing to say one has unwavering faith in something when one has studied it for years or decades or practiced it a little with good results, but this is a wide world and the mind is organized in hierarchies and unless the person has crossed the line marked by the 'Dhamma Eye': "all things that have come into existence are destined to come to an end" the mind which had latched onto faith through fear (not a high level in the hierarchy) could find a greater satisfaction in someone dying on the cross for their sins, for example, or in the idea that there was no self, or in the idea that this was a one-shot thing and there was no possibility of having to pay up, than in concepts such as compassion, giving or ethical behavior ... themselves not high up in the pecking order. In fact, faith based on such things is one of the three things that the usual definition of the Streamwinner suggests must be broken. Still the possibility exists that a person with no more than a faith that the Buddha taught a way to freedom, or a way to the end of pain, might tenaciously hold on to that faith at death and that tenacious hanging on could drag them into a rebirth where their faith could find growth and develop into knowledge and vision, so it is a true statement to say it can be done by faith alone.

One more thing: there was a point not too far back where many of those of us who had faith in Gotama's teaching were trying to make the idea of faith sound palatable to a population heartily disenchanted with a faith that depended on faith that had proved incapable of inspiring its leaders to remain on the path of righteousness, so to speak. There was a big effort to convince everyone that faith in Buddhism was not faith, but 'confidence' [e.g. Bhk. Bodhi in his translation of this sutta] or 'conviction' [Bhk. Thanissaro] or 'trust' or 'well-reasoned or grounded trust' [me], but here the plain fact of the case is that this sutta is speaking about blind faith and I think we need to accept the fact that there is this level of trust, conviction and confidence in Gotama and his system as well and that it is not without good results. There are those of us who would like to think of Gotama's system as mathematically pure science, which it is, but we need also to recognize that there are those who have blind faith even in pure mathematics, and that it is not therefore a danger to the system that there are such believers. ... it's when a person has confidence and conviction that their blind faith is well grounded and starts proselytizing that the trouble starts, but that is another story.

PTS: Unwavering, V.81

BD: A Satisfying Certainty, Olds, trans.

WP: Unwavering, 1419

#65: Paṭhama Sukha Suttṃ, V.120

Sariputta gives the Wanderer Samandakani a brief definition of the Buddhist view of pain and pleasure.

PTS: Weal and woe a, V.82

ATI: First Discourse on the Pleasant K. Nizamis, trans.

WP: Happiness (1), 1420

#66: Dutiya Sukha Suttaṃ, V.121

Sariputta describes the experience from within this Dhamma and Discipline that it is discontented that one feels pain and contented that one feels pleasure.

PTS: Weal and woe b, V.83

ATI: Second Discourse on the Pleasant K. Nizamis, trans.

WP: Happiness (2), 1420

#67: Paṭhama Naḷakapāna Suttaṃ, V.122

The Buddha asks Sariputta to deliver a discourse. Sariputta likens the presence or absence of ten qualities leading to decline or growth to the waning and waxing of the moon.

PTS: At Nalakapana a, V.83

WP: Naḷakapāna (1), 1421

#68: Dutiya Naḷakapāna Suttaṃ, V.125

The Buddha asks Sariputta to deliver a discourse. Sariputta likens the presence or absence of ten qualities leading to decline or growth to the waning and waxing of the moon.

PTS: Nalakapana b, V.85

WP: Naḷakapāna (2), 1421

#69: Paṭhama Kathā-vatthu Suttaṃ, V.128

On proper topics of talk. Note that included in the topics of talk called 'animal talk' which should be avoided is talk about existence and non-existence of things. This includes 'self' — the discussion of whether or not there is a self, the statement that 'There is no self', are not proper subjects for discussion. The topic suitable for discussion is that there is 'no thing there that is the self'. The former is an opinion, the latter is something that can be observed.

PTS: Topics of talk a, V.86

ATI: Topics of Conversation Thanissaro Bhikkhu, trans.

BD: Topics of Talk, Olds, trans.

WP: Topics of Discussion (1), 1424

#70: Dutiya Kathā-vatthu Suttaṃ, V.129

The ten topics of talk, and the praiseworthiness of those who make such talk, encourage others to talk such talk, and who engage in the behavior indicated by such talk.

PTS: Topics of talk b, V.88

ATI: Topics of Conversation (2) Thanissaro Bhikkhu, trans.

WP: Topics of Discussion (2), 1425

VIII. Ākaṅkha-Vagga, V.131

PTS: On Wishes, V.89

WP: Wish, 1426

#71: Ākaṅkheyya Suttaṃ, V.131

The Buddha enumerates 10 frequent wishes of bhikkhus and stresses that to bring them to fruition it is necessary to develop ethical culture following the rules and training principles of the Patimokkha.

PTS: Wishing, V.89

ATI: Wishes

WP: Wish, 1426

#72: Kaṇṭaka Suttaṃ, V.133

The Buddha teaches of ten things which are thorns to one who is actively practicing.

PTS: The thorn (in the flesh), V.91

ATI/DTO: Thorns, Bhk. Thanissaro, trans.

WP: Thorns, 1428

#73: Iṭṭha-dhamma Suttaṃ, V.135

Ten things that are much wished for, but hard to get in the world; ten things that are obstacles to getting them and ten things that are helpful for getting them.

PTS: Desirable, V.92

ATI/DTO: Wished For, Bhk. Thanissaro trans.

WP: Wished For, 1429

#74: Vaḍḍha Suttaṃ, V.137

Directed at laymen, the Buddha describes ten things which one should make an effort to grow and which should be considered as consistent with progress on the Way.

PTS: Growth, V.93

WP: Growth, 1430

#75: Migasālā Suttaṃ, V.137

Migasālā confronts Ānanda in a huff because of her confusion over the fates of her father and uncle. Both were declared to have been reborn in the Tusita realm as Once-returners by the Buddha. Her father was proficient in ethical conduct but deficient in wisdom, her uncle proficient in wisdom but deficient in ethical behavior, but Migasala only sees one side: that her father was proficient in ethical behavior and her uncle was not; and she proceeds to judge the Buddha and the Dhamma as flawed. Gotama explains the issue to Ānanda and gives five similar cases. Another version of the sutta is at AN 6.44.

PTS: Migasālā, V.94

ATI/DTO: About Migāsālā, Bhk. Thanissaro, trans.

WP: Migasāla, 1430

#76: Tayo-Dhamma Suttaṃ, V.144

A paṭicca-samuppāda-like (this being that becomes, from the ending of this, the ending of that) progression of 10 steps of three factors each showing how lack of sense of shame, a fear of blame and being careful prevents growth in the ability to eliminate lust, hate and delusion, factors necessary for attaining freedom from birth, aging and death. Followed by the reverse course showing how sense of shame, a fear of blame, and being careful end up leading to the elimination of lust, hate, and delusion and the end of birth, aging and death. Followed by the reverse course showing how sense of shame, a fear of blame, and being careful end up leading to the elimination of lust, hate, and delusion and the end of birth, aging and death. Here again the dependence is not cast in terms of 'cause' but of ability to grow.

PTS: Unable to Grow, V.99

ATI/DTO: Incapable, Bhk. Thanissaro trans.

WP: Incapable, 1434

#77: Kāka Suttaṃ, V.149

The Buddha enumerates 10 qualities of a crow which are found also in a wicked bhikkhu. This is a sutta which must be read in the Pāḷi to see the humor. You can do it! It's very short, and the humor can be easily seen. And you will never forget the Pāḷi word for 'and'. In this sutta and the next there is the use of the word "Dhamma" that falls between the meaning as 'phenomena' or 'thing' and The Dhamma, as in the Teachings of the Buddha. Here it has the meaning of 'Good Form' as given by Rhys Davids, [see Buddhist India pg 292] or of the Chinese 'Tao'.

PTS: The Crow, V.101

WP: The Crow, 1439

#78: Nigaṇṭha Suttaṃ, V.150

The Buddha enumerates 10 things about the Niganthas, (the naked ascetics), which do not comport with Dhamma, 'Good Form.'

PTS: The Unclothed, V.101

WP: The Nigaṇṭhas, 1439

#79: Āghāta-vatthu Suttaṃ, V.150

The Buddha lists 10 thoughts that tend to provoke anger. These lists are very valuable as they pop into the mind at those times when one is about to cross a line and can give one just enough detachment (self-reflection) to correct course. The secret is in their broad-based generality. For five methods for overcoming anger see the next, and AN 5.161

PTS: Occasions of ill-will, V.102

WP: Grounds (1), 1439

#80: Āghāta-paṭi-vinaya Suttaṃ, V.150

The Buddha suggests ten thoughts as counter-weights to the arising of anger possible from ten situations where anger might arise (those of the previous sutta). Our version of the BJT Pāḷi was incomplete for this and the previous sutta. This may have been corrected, but readers of that version should check. Woodward and Bhks. Thanissaro and Bodhi have trouble with the phrase: 'taṃ kut'ettha labbhā' ti? 'What is to be gained from that?' The meaning is understood if kamma is kept in mind. The idea is to calm one's tendency to an angry reaction by remembering that this deed this fellow does will return to him and that therefore there is no need to seek vengeance from a feeling of outrage at injustice. Alternatively it can be understood as asking one's self how one can profit from the situation: like taking it as a lesson.

PTS: Ways of checking ill-will, V.

ATI: Hatred

WP: Grounds (2), 1440

IX. Thera-Vagga, V.151

PTS: The Elders, V.103

WP: The Elders, 1440

#81: Bāhuna Suttaṃ, V.151

Ten barriers that are to be broken down by one who would be free, detached and released.

PTS: Bāhuna, V.103

ATI: To Bahuna

BD: Old Man Bāhuna

WP: Bāhuna, 1440

#82: Ānanda Suttaṃ, V.152

Ten things which prevent increase, growth and maturity in this Dhamma-discipline and ten things which promise increase, growth and maturity in this Dhamma-discipline.

PTS: Ānanda, V.103

BD: Ānanda, Olds, trans.

WP: Ānanda, 1441

#83: Puṇṇiya Suttaṃ, V.154

Punniya, asks why it is that sometimes the Buddha will teach and sometimes not. Gotama explains that there are ten factors involved, but that more than the simple ten factors what is needed is to see progress up the ten factors in a bhikkhu. So sometimes a teaching may be given with only some of the factors and other times not when even one is missing. This is the experience of the modern practitioner of the system as well: it seems to get more demanding the further into it one gets. This sutta looses all its power and elegance when abridged; here both the Pāḷi and Woodward translation are completely rolled out.

PTS: Puṇṇiya, V.104

WP: Puṇṇiya, 1441

#84: Vyākaraṇa Suttaṃ, V.155

Mahā Moggallāna describes the examination that will be given to one who declares arahantship by those who are Arahants, skilled in the jhānas and able to read the state of and habits of the hearts of others. Possessing any of ten characteristics he will come to an impasse and ruin when questioned. But if one abandons all these ten characteristics he may come to increase, growth and maturity in this Dhamma-discipline.

PTS: Declaration of Gnosis, V.105

WP: Declaration, 1442

#85: Katthi Suttaṃ, V.157

Cunda the Great puts his spin on the previous sutta. In this case a boaster brags of attainments and is questioned by one skilled in the jhānas and able to read the state of and habits of the hearts of others. Possessing any of ten characteristics he will come to an impasse and ruin when questioned. But if one abandons all these ten characteristics he may come to increase, growth and maturity in this Dhamma-discipline.

PTS: The Boaster, V.106

WP: The Boaster, 1444

#86: Adhimāna Suttaṃ, V.161

Kassapa the Great puts his spin on the theme of the previous two suttas. Maha Kassapa deals with the case of a bhikkhu who, due to confusion of mind created by great learning, thinks he has attained arahantship. He is questioned by one skilled in the jhānas and able to read the state of and habits of the hearts of others. Possessing any of ten characteristics he will come to an impasse and ruin when questioned. But if one abandons all these ten characteristics he may come to increase, growth and maturity in this Dhamma-discipline. The ten characteristics in each of these cases is slightly different. Each of these versions reflects the character and special interests of the speaker.

PTS: The Question of Gnosis, V.108

WP: Final Knowledge, 1446

#87: Adhikaraṇika Suttaṃ, V.164

The Buddha enumerates ten things which if absent do not conduce to affection, respect, progress, harmony and unity, but which if present do conduce to these things.

PTS: Kālaka the monk, V.110

WP: Disciplinary Issues, 1449

#88: Akkosaka Suttaṃ, V.169

The Buddha declares ten misfortunes one or another of which are unavoidable by a bhikkhu that abuses his fellows in the Brahma Life. This sutta is directed at bhikkhus, but should be taken seriously by laymen as well.

PTS: Disaster (a), V.112

WP: One Who Insults, 1452

#89: Kokālika Suttaṃ, V.170

A well-known sutta describing the horrific result of hardening his heart against Sāriputta and Moggallāna by the Kokālikan Monk. This sutta has in it the mention of a 'pacceka-brahmā.' Bhk. Bodhi, in a footnote, cites Spk-pṭ I 213 (VRI ed) commenting on SN I 146, as explaining this as "a Brahmā who travels about alone, not as a member of an assembly". This possibly throws some light on the term 'pacceka-buddha' which is usually translated 'silent-buddha' or as Woodward has translated it here for the Brahmā, 'Individual-'. This term, when applied to a Buddha, means an individual who attained Arahantship without the aid of another awakened individual but who has not the training or charisma or inclination or opportunity to lead a following. There is also here another visit to Gotama by Brahmā Sahampati.

One other interesting thing in this sutta is the case of a non-returner returning to this world for a visit. We need, in thinking of the non-returner in order not to make the mistake made by Kokalika, to think in terms of rebirth, not freedom of movement. [For another case of a Non-returner returning to this world for a visit see AN 3.125.]

PTS: The Kokalikan, V.113

WP: Kokālika, 1452

#90: Khīṇ-āsava-bala Suttaṃ, V.174

The powers (balani) of one who has destroyed the corrupting influences which give him the knowledge to know that he has destroyed the corrupting influences (āsavas). As well as a good way to know when you really know, this is a good curriculum for plotting one's course to the goal.

PTS: The Powers, V.

WP: Powers, 1455

X. Upāsaka-Vagga, V.176

PTS: The Lay-Followers, V.119

WP: Upāli, 1456

#91: Kāmabhogī Suttaṃ, V.176

Gotama speaks to the wealthy banker Anāthapiṇḍika, breaking down the distinctions between sorts of persons who are still enjoyers of sense pleasures according to the extent they earn their wealth legitimately and dispense with it wisely.

Mark Twain used to do a routine where he would stand in front of his audience and tell a feeble, possibly even tedious joke or story. When he got no reaction from the audience except embarrassment, he told the story again without altering a word or changing an inflection. He would repeat this routine as many times as necessary to bring the house down with laughter. It never failed.

My father used to tell the story of a comedian who would enter a bare stage with only a wooden chair on it, sit on the chair, and do nothing more until bit by bit there would be a snicker from someone in the audience, or a smile, and before long this non-act would bring the house down with laughter. It never failed.

There is something about repetition (or its alter-ego, nothing at all happening, as with the experience of those who seek solitude) that, if endured to a certain point (passed a murky sloth), forces the mind into an elevated state, wakes it up to a grander scope.

It is just this sort of psychology that is being used by Gotama in the case of this and so many other suttas considered 'tedious' by translators and readers today [Wednesday, December 18, 2013 10:07 AM]. The reader may be given some slack. The written word carries little or none of the magic of a live performance. But the reader must accept his disadvantage and make up for it with imagination. Dwell on such a sutta as this. Place yourself in the situation as you imagine it happening at the time. It will come to life. It never fails.

Something important for translators to remember in this regard is to not yield to the impulse to change the wording for variety. Follow the Pāḷi. The Pāḷi is mathematically consistent, and this is a necessity for the mind to keep track of the variations in the pattern. Inserting difference to break tedium destroys the pattern in exactly the same way as if when weaving a rug one were to alter the pattern simply because it was the same all round. Translators may think they are helping the reader, but they are breaking the spell and this is all the greater crime because it is not suspected that there is a spell there that is being broken and the changes make it much more difficult to discover. This is just as much the case in the case of the whole body of suttas, but is very difficult and has not been managed to this point by any translator. A uniform translation vocabulary across all the suttas should be made the goal of the next generation of Dhamma translators.

PTS: Pleasures of Sense, V.119

WP: One Who Enjoys Sensual Pleasures, 1456

#92: Bhaya Suttaṃ, V.182

Gotama explains to Anāthapiṇḍika how one may know with certainty that one is a Streamwinner and that one has passed beyond the reach of certain unpleasant forms of rebirth and is assured of eventual awakening. The careful reader can see in this sutta how development of ethical behavior leads to unwavering faith in the Buddha, Dhamma and the Saṅgha which leads to insight into the method.

The term translated 'Guilty Dread' by woodward and 'fear and animosity' by Bhk. Thanissaro and 'perils and enmities' by Bhk. Bodhi is bhayāni verāni. bhayāni = fear, fright, dread; verāni = hatred, revenge, hostile action. A possible better translation is 'fear of retribution', which is what makes up guilty dread and is the peril of enmity and the fear of animosity. These actions are perils and do produce enmities and fear and animosity both in the doer and in others, but the issue in this sutta is a condition for knowing that one is a Streamwinner and that condition is the absence of or allaying of bhayāni verāni. within. It has nothing to do with what may result externally from these actions.

This is a good sutta to contrast with AN 10.64 where faith alone is being spoken of as a condition for stream-entry. It should be noted here that in both cases there is no mention of breaking the saṇyojana. That is not to say they are not broken, but only to point out that the formal terminology is not used and because of that there is the possibility of flexible understanding of the conditions. Possessing the four limbs of Stream-winning would be the breaking of doubt and wavering (vicikiccha); true insight into 'the method' would be the breaking of the 'one truth view' (sakkāya-diṭṭhi usually translated in terms meaning 'own-self-view': 'Person-pack-view' 'views on individuality' etc., my translation, points to the idea that it is getting rid of holding any view concerning the existence of anything that is the necessary meaning in that holding on to a view concerning the existence of anything is a projection of the idea of self, but perhaps that is going farther than is necessary, or even confusing the issue) and attachment to the view that the goal was reachable through giving, ethical conduct, or rituals (sīlabbata-parāmāso). One can imagine (or experience) a situation where one or some or all of these conditions are only partially met here, but where with faith in the Dhamma, or in the idea that Gotama achieved Awakening, or in the idea that there were those who had advanced towards the goal, upon death or upon the subsequent rebirth they come to fulfillment. That person would by that faith and partial accomplishment reasonably be called a stream-winner. On the other hand, that person would not be able to state with absolute conviction, that he was a stream-winner. Hopefully reflecting on this sutta would, in that case, inspire greater effort.

PTS: Guilty Dread, V.124

ATI: Animosity

WP: Enmity, 1462

#93: Kiṃ-diṭṭhika Suttaṃ, V.185

Anāthapiṇḍika visits wanderers of other views, listens to their views and shows the wanderers how, in each case, the view is just a grasping after security based on something theoretical, made up, and which will lead to pain. When asked about his own views he responds that it is a not-clinging to things that are graspings after security based on things theoretical, made up, and which will lead to pain. This sutta amounts to a statement by Anāthapiṇḍika that he was at this time a stream-winner who 'knew and saw', one who had the Dhamma-eye: That all things that have come to be come to an end. After his death he was pronounced a Non-returner by Gotama.

PTS: View, V.127

ATI: Views

WP: View, 1464

#94: Vajjiyamāhita Suttaṃ, V.189

Vajjiyamāhita visits wanderers of other views and corrects their understanding of Gotama's position on austerities pointing out that he teaches discriminating between the profitable and the unprofitable. Vajjiyamāhita reports back to Gotama and the Buddha elaborates this position in terms of austerities, trainings, making effort, letting go, and freedom. Vajjiyamāhita is one of twenty other laymen said to have achieved 'realization of the deathless' in AN 6.147.

PTS: Vajjiyamahita, V.130

ATI: About Vajjiya

WP: Vajjiyamāhita, 1467

#95: Uttiya Suttaṃ, V.193

Uttiya the wanderer asks Gotama what he says about ten well-known questions concerning existence and non-existence each of which is answered by the statement by the Buddha that he has not made a declaration concerning the truth of that issue. Two additional question are: What then do you teach? and Will everyone be saved by this teaching?

The ten questions are the ones made famous by those who say that Gotama did not answer certain questions. That statement is a careless reading and mistaken. Here we see Gotama has not not answered the questions, he has answered by saying that he has not made an assertion of the truth or falsity of the proposition. This is not the same thing as not answering. If pressed for his reason for not making a declaration, (which Uttiya does not do in this sutta) Gotama explains that such questions are all based on points of view and consequently are true under only some ways of looking at things, false under others. Consequently if asked the simple question 'is this true?' there is no possible answer but that no one-sided declaration can be made about such an issue. Since with regard to the ten questions Gotama is being asked directly (that is, he is not being asked at this point what he has to say in general about this point of view) and only about his opinion as to the truth or falsity of the view, his only possible truthful answer is that he has not made a declaration (one way or the other) on that issue. When Uttiya asks about what Gotama does teach, he gets the other answer supplied to those who ask such questions: what he teaches, avoiding issues of existence and non-existence, is pain, the origin of pain, the ending of pain and the way to the ending of pain. (Stated in different terms in this sutta ... which is a notable fact in itself: no mention of the four truths or the eightfold way.)

This may look like nit picking, but it is of vital concern as it is a pivotal point for the mind. (It also demonstrates how the awakened mind listens to and responds to questions!) Comprehension of why these are not fruitful inquiries leads to comprehension of the middle way and how it solves the problem of the pain associated with existence.

For translators also it is vital. Not comprehending this balance between issues of existence and non-existence, translations will tend to use terms bound up in those very issues (e.g. 'no self' for anatta: which is, correctly, 'not- or non-self') and by that not point to freedom.

PTS: Uttiya, V.133

ATI: To Uttiya

WP: Uttiya, 1470

#96: Kokanada Suttaṃ, V.196

Kokanuda the wanderer asks Ānanda about whether or not he holds any of ten well-known views concerning existence and non-existence each of which is answered by the statement by Ānanda that he does not hold such a view. When questioned further Ānanda explains that these are just points of view, fixing on points of view, reliance on points of view, obsession by points of view and as such are things that should be let go (risen up from) and rooted out.

PTS: Kokanuda, V.135

ATI: To Kokanuda (On Viewpoints)

WP: Kokanada, 1472

#97: Āhuneyya Suttaṃ, V.198

Ten qualities which make for a bhikkhu that is worshipful, worthy of honor, worthy of offerings, worthy of being sainted with clasped hands, a field of merit unsurpassed for the world.

PTS: Worshipful, V.137

WP: Worthy of Gifts, 1473

#98: Thera Suttaṃ, V.201

Ten attributes of a Thera (a bhikkhu of long standing) wherewith he is able to live happily wherever he lives.

PTS: The Elder Monk, V.139

WP: An Elder, 1475

#99: Upāli Suttaṃ, V.201

Upāli has got it into his head that he wants to become a forest-dwelling bhikkhu. The Buddha, apparently perceiving disaster for him in this course, in that those without mastery of serenity (as was the case with Upāli,) are highly vulnerable, living in the forest, to either failure due to unskillful states of mind or to just not making any headway at all, discourages him with a long discourse on what actually needs to be accomplished in this system to achieve the goal. Upāli, by the way, follows the Buddha's advice and remains dwelling with the saṅgha and becomes one of the foremost bhikkhus in the understanding of the Vinaya, or rules of the order.

PTS: Upāli, V.140

ATI: To Upāḷi, Bhikkhu Thanissaro translation

WP: Upāli, 1476

#100: Bhabbābhabba Suttaṃ, V.209

The Buddha enumerates ten things which if not abandoned prevent achieving arahantship, if abandoned conduce to arahantship.

PTS: Unfit to Grow, V.147

WP: Incapable, 1482

XI. Samaṇa-saññā-Vagga, V.210

PTS: Ideas of a Recluse, V.148

WP: An Ascetic's Perceptions, 1483

#101: Samaṇa-saññā Suttaṃ, V.210

When three things about the reality of his situation as a bhikkhu are perceived it results in the fulfillment of seven highly advantageous conditions in his life.

PTS: Ideas, V.148

BD: A Seeker's Perceptions, Olds, trans.

ATI/DTO: Contemplative Perceptions, Bhk. Thanissaro trans.

WP: An Ascetic's Perceptions, 1483

#102: Bojjh'aṅga Suttaṃ, V.211

The Buddha explains that the seven dimensions of self-awakening lead to the three-fold vision of the Arahant.

PTS: Limbs of wisdom, V.148

WP: Factors of Enlightenment, 1483

#103: Micch'atta Suttaṃ, V.211

The Buddha explains how the low road leads to failure and the high road leads to success. The exposition of the two paths is in a paṭicca-samuppāda-like formula: 'this being that becomes'; and consists of the positive and negative dimensions of the Seeker's Path, the Eightfold path with the two additional dimensions of knowledge and release. No mention is made of the Eightfold Path or the Seeker's Path. Woodward translates 'sammā' and 'micchā' as right and wrong, which would be better as 'high' and 'low', or 'consummate' and 'contrary' or 'misguided'. For discussion of these terms see: On "Sammā" "Miccha," "Ariya," and "Angika"

PTS: Wrongness, V.149

ATI: Wrongness Bhk. Thanissaro, trans.

BD: The Low, M. Olds, trans.

WP: The Wrong Course, 1484

#104: Bīja Suttaṃ, V.212

The Buddha explains how the low road leads to bad luck and the high road leads to good luck using a simile likening point of view to a seed. If the seed is one of a bitter plant, the results are bitter, if the seed is one of a sweet plant, the results are sweet.

PTS: The Seed, V.150

ATI: The Seed Bhk. Thanissaro, trans.

WP: A Seed, 1485

#105: Vijjā Suttaṃ, V.214

The Buddha explains in a paṭicca-samuppāda-like style how blindness (a-vijjā) (non-vision), leads to shameful behavior and that gives rise to mistaken points of view which leads to false release. Where there is vision (vijjā; 'seeing' the bad consequences of shameful acts) gives rise to consummate point of view which leads to consummate release.

PTS: By knowledge, V.151

WP: True Knowledge, 1486

#106: Nijjara Suttaṃ, V.215

A paṭicca-smuppāda-like progression of things each of which wears out the next ending in release.

PTS: Causes of Wearing Out, V.151

WP: Wearing Away, 1486

#107: Dhovana Suttaṃ, V.216

Taking his inspiration from a bone-washing ancestor-worship ritual the Buddha speaks of his teaching as a washing of a different sort, one leading to Nibbāna.

PTS: The Ablution, V.152

WP: Dhovana, 1488

#108: Tiki-c-chaka Suttaṃ, V.218

As doctors administer a purge, so the Buddha administers a different sort of purge, one leading to Nibbāna.

PTS: Physic, V.153

ATI: A Purgative

WP: Physicians, 1489

#109: Vamana (Niddha-manaṃ) Suttaṃ, V.219

As doctors administer an emetic, so the Buddha administers a different sort of emetic, one leading to Nibbāna.

PTS: Ejection, V.154

WP: Emetic, 1490

#110: Niddha-maniya Suttaṃ, V.220

Ten negative things which are ejected by their opposites in a process leading to Nibbāna.

PTS: To be Ejected, V.154

WP: Ejected, 1491

#111: Paṭhama A-sekha Suttaṃ, V.221

The ten attributes that define the a-sekha (the non-seeker, one who is no longer a seeker because he is an adept.)

PTS: Adept a, V.154

WP: One Beyond Training (1), 1491

#112: Dutiya A-sekha (Asekhiya-Dhamma) Suttaṃ, V.222

The ten attributes that define the a-sekha (the non-seeker, one who is no longer a seeker because he is an adept.) Probably 'adept' is the best translation we are going to get for this term in so far as the truer negative form 'a-sekha' always seems to come out in English as one who isn't even trying, has given up, or is hopeless. In a certain sense though the idea that one has given up seeking is the original meaning in that there is nothing the 'adept' here is adept at except no longer seeking.

PTS: Adept b, V.154

WP: One Beyond Training (2), 1492

XII. Paccorohaṇi-Vagga, V.222

PTS: The Descent, V.155

WP: Paccorohaṇī, 1492

#113: Paṭhama A-Dhamma Suttaṃ, V.222

The Buddha states that both what is and what is not good form and the goal should be understood and then enumerates ten general areas to be considered good form and which are the goal and ten which are not good form and which are not the goal.

PTS: Not-Dhamma a, V.155

WP: Non-Dhamma (1), 1492

#114: Dutiya A-Dhamma Suttaṃ, V.223

The Buddha states that both what is and what is not good form and the goal should be understood and then enumerates ten general areas to be considered good form and which are the goal and ten which are not good form and which are not the goal.

PTS: Not-aim b, V.155

WP: Non-Dhamma (2), 1493

#115: Tatiya A-Dhamma Suttaṃ, V.224

The Buddha states that both what is and what is not good form and the goal should be understood and then retires to his cell. The bhikkhus ask Ānanda to elaborate. Ānanda enumerates ten general areas to be considered good form and which are the goal and ten which are not good form and which are not the goal. A variation and expansion of the previous sutta. This sutta has been expanded according to the indications in the Pāḷi. The indications, however are not the usual ones, but appear to be attempts to create a style of abridgment close to what we find today where it is merely stated that there is a repetition of a previous passage. That is particularly unfortunate here as what we have from the beginning of this chapter (AN 10.113 on) is otherwise a good example of what was a regular pattern in the dissemination of an approach to the Dhamma. First comes the doctrine stated in brief by Gotama. Then comes one or more orthodox expansions by Gotama. Then comes a statement in brief to bhikkhus who then seek out the expansion from one of the elders. There is further evolution as in the next suttas, in some cases with the expansion being given by more than one elder, and sometimes with acceptable variations. Those interested in the history and methods of propagation of the Dhamma should take note.

PTS: Not-Dhamma c, V.156

WP: Non-Dhamma (3), 1494

#116: Ajita Suttaṃ, V.229

Ajita approaches the Buddha and describes what he understands to be a sage. Gotama responds by describing that a sage in this system is to be understood as one who argues according to Dhamma. Gotama then enumerates ten general areas to be considered good form and which are the goal and ten which are not good form and which are not the goal. An expansion on the previous suttas. There is a big problem with this sutta. No single version of the Pāḷi or translation agrees with anything else.

PTS: Ajita, V.159

BD: Ajita, Olds, trans.

WP: Ajita, 1497

#117: Saṅgārava Suttaṃ, V.232

Brahmin Sangarava asks the Buddha about the meaning of the expressions 'the hither shore' and 'the further shore'.

PTS: Sangarava a, V.160

WP: Saṅgārava, 1499

#118: Orimatīra Suttaṃ, V.233

The Buddha tells the bhikkhus about the meaning of the expressions 'the hither shore' and 'the further shore'. In this and the previous sutta is another frequent method of sutta dissemination. A chance conversation yields a useful exposition. Nothing is wasted. It is repeated to the bhikkhus. Pass the word friends!

PTS: Hither and further shore a, V.161

WP: Near, 1500

#119: Paṭhama Paccorohaṇī Suttaṃ, V.233

The Buddha explains the difference between the Brahmin ceremony of descent into the fire, with the descent of the Aristocrats.

PTS: The Ariyan Descent a, V.161

WP: Paccorohaṇī (1), 1500

#120: Dutiya Paccorohaṇī Suttaṃ, V.236

The Buddha explains the 'Descent of the Aristocrats'.

PTS: The Ariyan descent b, V.163

WP: Paccorohaṇī (2), 1502

#121: Pubbaṇ-gama Suttaṃ, V.236

As the dawn is the first sign of sunrise, so high view is the first sign of the arising of all good states.

PTS: The harbinger, V.164

WP: Forerunner, 1503

#122: Āsava-k-khaya Suttaṃ, V.237

The Buddha enumerates ten steps which lead to the destruction of the corrupting influences.

PTS: Cankers, V.164

WP: Taints, 1503

Many of the following suttas give the ten-fold path in brief. The definitions of these terms can be found, in among other places:

The Method

in MN 22 Mahā Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta (under the section on Dhamma; but the first eight only)

The Pāḷi Line, Lesson 10

I have provided links for many of these suttas to the Rhys Davids translation of the Mahā Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta definitions for the first eight terms and to The Method for the last two terms.

![]() — p.p.

— p.p.

XIII. Pari-suddha-Vagga, V.

PTS: Perfect Purity, V.165

WP: Purified, 1503

#123: Paṭhama Suttaṃ, V.237

Ten states of perfect purity and clarity found only in the Buddha's Discipline.

PTS: States of Perfect Purity, V.165

WP: First, 1503

#124: Dutiya Suttaṃ, V.237

Ten states which, if not yet arisen, do not arise except in the Buddha's Discipline.

PTS: States Not Yet Arisen, V.165

WP: Second, 1503

#125: Tatiya Suttaṃ, V.238

Ten states of great fruit and advantage found only in the Buddha's Discipline.

PTS: States of Great Fruit, V.165

WP: Third, 1503

#126: Catuttha Suttaṃ, V.238

Ten states that bring lust, hate and stupidity to an end found only in the Buddha's Discipline.

PTS: Ending in Restraint, V.165

WP: Fourth, 1504

#127: Pañcama Suttaṃ, V.238

Ten states that lead to disgust, fading out, ending, calm, understanding, awakening, and Nibbāna found only in the Buddha's Discipline.

PTS: Conducive, V.165

WP: Fifth, 1504

#128: Chaṭṭhama Suttaṃ, V.238

Ten states which if worked at arise only in the Buddha's Discipline.

PTS: Made to Grow a, V.166

WP: Sixth, 1504

#129: Sattama Suttaṃ, V.239

Ten states which if developed are of great fruit only in the Buddha's Discipline.

PTS: Made to Grow b, V.166

WP: Seventh, 1504

#130: Aṭṭhama Suttaṃ, V.239

Ten states which if worked at end in restraint of lust, hate and stupidity, but only in the Buddha's Discipline.

PTS: Made to Grow c, V.166

WP: Eighth, 1504

#131: Navama Suttaṃ, V.239

Ten states which if worked at lead to disgust, fading out, ending, calm, understanding, awakening, and Nibbāna are found only in the Buddha's Discipline.

PTS: Made to Grow d, V.166

WP: Ninth, 1504

#132: Dasama Suttaṃ, V.240

Ten low states.

PTS: Wrong, V.166

WP: Tenth, 1505

#133: Ekādasama Suttaṃ, V.240

Ten high states.

PTS: Right, V.166

WP: Eleventh, 1505

XIV. Sādhu-Vagga, V.240

PTS: The Seemly a, V.167

WP: Good, 1505

#134: Sādhu Suttaṃ, V.240

Ten things which are well done and ten things which are not well done.

PTS: Right and Wrong, V.167

WP: Good, 1505

#135: Ariya-Dhamma Suttaṃ, V.241

Ten things which are aristocratic and ten things which are not aristocratic.

PTS: Ariyan and unariyan, V.167

WP: 135-144. The Noble Dhamma, Etc., 1505

#136: Kusala Suttaṃ, V.241

Ten things which are skillful and ten things which are not skillful.

PTS: Good and Bad, V.167

WP: 135-144. The Noble Dhamma, Etc., 1505

#137: Attha Suttaṃ, V.241

Ten things which are not the goal and ten things which are the goal.

PTS: Aim and Not-aim, V.167

#138: Dhamma Suttaṃ, V.242

Ten things which are Dhamma and ten things which are Not-Dhamma.

PTS: Dhamma and Not-Dhamma, V.167

#139: S'āsava Suttaṃ, V.242

The Buddha defines a path that allows in corrupting influences and one which does not allow in corrupting influences.

PTS: With Cankers and Without, V.167

#140: Sāvajja Suttaṃ, V.242

The Buddha defines a path which has aspects which should be avoided and one which has no fearful aspects.

PTS: Blameworthy and Blameless, V.168

#141: Tapanīya Suttaṃ, V.243

The Buddha defines a path which brings remorse and a path that brings no remorse.

PTS: Remorse and Not-remorse, V.168

#142: Ācaya-gāmī Suttaṃ, V.243

The Buddha defines a path which heaps up rebirth and a path that is beyond heaping up rebirth. PED has 'apacaya' as 'unmaking' or 'diminishing' which is also the way Woodward (diminishing) and Bhk. Bodhi (dismantling) translate. PED forms the word from 'apa + ci" 'up passed-whatever.' A simpler reading would be that the root is 'caya' 'heap' and the prefixes are 'ā' 'to' and 'apa' 'up-passed.' The importance is in whether or not what is being said is that the path dismantles the existing pile of future rebirths, or does not create any new future rebirths. It works both ways.

PTS: Given to Heaping Up and Diminishing, V.168

#143: Dukkh-u-draya Suttaṃ, V.243

The Buddha defines a path which yields up pain and a path that yields up pleasure.

PTS: Yielding Pain and Pleasure, V.168

#144: Dukkha-vipāka Suttaṃ, V.244

The Buddha defines a path which ripens in pain and a path that ripens in pleasure. Woodward following PED translates 'vipāka' 'ripening', as 'fruit' meaning 'fruition'. Since 'phala' which is 'fruit' is often used in the Suttas the better translation would be the literal 'ripening' or 'fruition' or along the lines of 'consequence' 'result', etc.

PTS: Pain and Pleasure, V.168

XV. Ariya-magga-Vagga, V.244

PTS: The Ariyan Way a, V.168

WP: Noble 1506

#145: Ariya-magga Suttaṃ, V.244

The Buddha defines the way of the Aristocrats and the way that is not the Way of the Aristocrats. Beginning a new set. It's like sandpaper. Round and round the basic two sets of ten 'dimensions' or 'steps' or 'folds' or 'facets' or 'things' or 'forms' or 'Teachings'. At some point or another, if paying close attention as requested, preconceptions about the path (about life!) will be sanded off. ... oops! There goes Mark Twain.

PTS: Ariyan and Unariyan, V.168

WP: The Noble Path, 1506

#146: Sukka-magga Suttaṃ, V.244

The Buddha defines the black way and the white way.

PTS: Bright Way and Dark Way, V.168

WP: 146-54. The Dark Path, 1506

#147: Sad'Dhamma Suttaṃ, V.245

The Buddha defines true Dhamma and untrue Dhamma.

PTS: True Dhamma and False Dhamma, V.169

#148: Sappurisa-Dhamma Suttaṃ, V.245

The Buddha defines the Dhamma of the good man and what is not the Dhamma of the good man.

PTS: Very-man Dhamma and Its Opposite, V.169

#149: Uppādetabba Suttaṃ, V.245

The Buddha defines Dhamma that should be made to arise and Dhamma that should not be made to arise.

PTS: To Be Brought About, V.169

#150: Āsevitabba Suttaṃ, V.246

Āsevi 'to revisit'. The Buddha defines Dhamma that should be pursued and that which should not be pursued.

PTS: To Be Followed, V.169

#151: Bhāvetabba Suttaṃ, V.246

The Buddha defines Dhamma that should be developed and Dhamma which should not be developed.

PTS: To Be Made to Grow, V.169

#152: Bahu-līkāttabba Suttaṃ, V.246

The Buddha defines Dhamma that should be made a big thing of and Dhamma which should not be made a big thing of.

PTS: To Be Made Much Of, V.169

#153: Anu-s-saritabba Suttaṃ, V.247

Anussarati Anu + sati. Remembrance. Memorization. Recollection, but deliberate and again and again. Bringing again and again to mind so as to establish it clearly in memory. The Buddha defines ten things which should be memorized and ten things which should not be memorized.

PTS: To Be Remembered, V.169

#154: Sacchi-kātabba Suttaṃ, V.247